In the neighborhood of Juárez, a vibrant artistic and historic area of Mexico City with LGBTQ bars and restaurants and a large Korean population, long-term renters are losing their homes as apartments are being converted into more profitable day-rate Airbnb rentals.

No studies have been conducted, but former residents say rental prices have more than doubled to prohibitive levels of 20,000 to 30,000 pesos per month. Before, 10,000 pesos (U.S. $520) was the norm, Dario Martínez told El Big Data after he had to leave his place in Juárez.

Truthout talked to members of a neighborhood group, 06000 Observa, about local organizing efforts to protect the area’s cultural heritage and housing rights in the historic center of Mexico City. Half of the members of the group — around 20 — say they have been affected by issues with Airbnb. For their safety — violence and harassment against those who speak out is common — they requested that their individual names not be used.

“Here in the historic center, we are aware of dozens of buildings that used to be social housing or middle-class housing that have now been completely converted into Airbnb. . . . The biggest apartment buildings are being converted into hotels, but when it isn’t possible to change the legal land use, they are converted into Airbnb,” the group told Truthout via email, listing buildings that fit that criteria. The Bamer building, one on Isabel la Católica street, a building called Casa Borda, and more. Casa Borda is a historic building that was once owned by José de la Borda, the richest man in Mexico during part of the 18th century.

Rosalba Loyde is a Mexico City-based expert in urban development and housing who has been advocating for laws that regulate companies like Airbnb. She stressed that the situation with Airbnb in Mexico City isn’t similar to the situation in Barcelona or New York, where local authorities have passed strict regulations on Airbnb use following strong opposition and protests.

“Some buildings are being remodeled in order to be used completely on the platform,” Loyde told Truthout.

“Generally, we’ve noted that some areas in particular are being emptied of their inhabitants — Juárez, San Rafael, Santa Maria de Ribera and the historic center . . . They’re being handed over to tourism, and the expulsion of the inhabitants isn’t peaceful — it comes with violent and forced evictions . . . supported by corruption in various institutions like the Public Registry of Property and courts,” 06000 Observa said.

The group described corrupt lawyers and “housing mafia” who use mechanisms within the city’s housing institute “to take possession of properties.”

The violent and corrupt real estate world precedes Airbnb, but it is a context the company happily benefits from. Recently, one housing rights activist, Carlos Acuña, was removed from his home by such “mafia,” he told Truthout, as the owners wanted to build a hotel. Acuña said his rent was paid, his contract was still valid, and a court case was pending against the building owner.

Even official figures show an increase in illegal evictions in Mexico City of 43 percent over the last four years — and these figures tend to be well below real numbers, due to the lack of trust in authorities. The evictions are often aggressive and ignore due process. Renters have describedreceiving death threats and being robbed as a form of intimidation to move.

“We’re worried that this is going to get even worse and that the long history of urban and worker resistance in these areas will eventually be erased . . . and the city will become a type of theme park for tourists where living is replaced by consuming,” 06000 Observa said.

Democratizing the economic benefits, or hoarding them?

Mexico City’s Zócalo was previously the ceremonial center of the Aztec city, Tenochtitlan, and it receives over 10 million visitors per year. (Tamara Pearson)

“To democratize the benefits of travel, Airbnb offers a sustainable alternative to the mass tourism that has been spreading in cities for decades,” Airbnb’s PR spin reads, in Spanish. However, in Mexico, it has evidently left its air mattress roots far behind and joined the property market.

Another huge company, Shell, announced a $300 million fund for “investing in natural ecosystems” earlier this year. The fund serves to paint Shell as eco-conscious, but it is tiny in comparison to Shell’s annual $388 billion revenue from oil and gas. Like Shell’s greenwashing, Airbnb’s messaging is trying to counter the reality that the company, instead of bringing benefits to all, is just helping the rich get richer.

Airbnb claims that its users spend twice as much money as other tourists, and that much of that money is spent away from hotel districts. Likewise, Mexico’s Competitiveness Institute (IMCO — a think tank that studies the economic and social factors affecting competitiveness) also argues that the company distributes the economic benefits of tourism to more people.

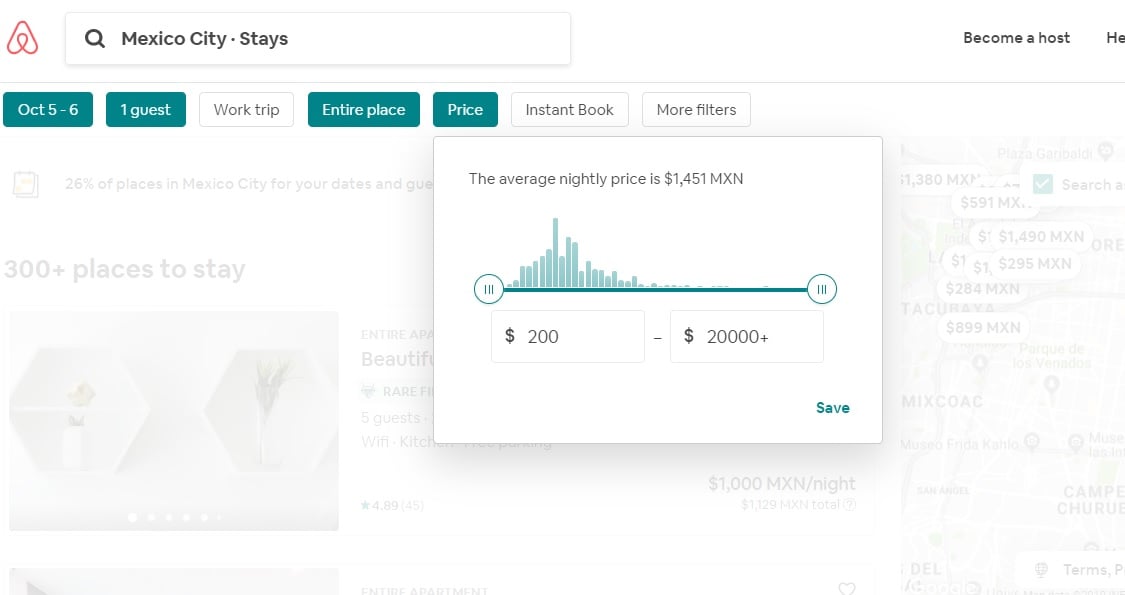

But in Mexico City, a solid 50 percent of those renting through Airbnb own and advertise multiple properties. Some 48.2 percent of the places advertised are full houses or apartments. The average price per night for a whole apartment is 1,451 pesos — an average week’s wage in Mexico.

This screenshot from https://www.airbnb.mx/ shows that the average price for an Airbnb apartment in Mexico City per night is 1,451 pesos. (Airbnb / Screenshot by Tamara Pearson)

Airbnb is based on a business model that takes advantage of market forces and a lack of laws or regulations. In most of Mexico, people renting out property through Airbnb don’t pay taxes on that income, resulting in a loss of 5 billion pesos (U.S. $250 million) per year, according to a study by Anáhuac University. Even Mexico’s Competitiveness Institute admitsthat Airbnb is increasing local rent rates.

“The Airbnb community benefits local economies across the world by supporting residents and local businesses, and encouraging cultural exchange,” the company states, though all 12 of the case studies behind that claim were in richer cities.

Airbnb’s impact is harsher in poorer countries. Mexicans are paid, on average, 12 percent of what people in the U.S. are. That context leads to businesspeople using Airbnb to prioritize Western tourists over the needs of peso-earning locals.

“Whitening through dispossession,” 06600 Observa, another neighborhood group based in Juárez, called it. Sergio González, a member of the group, told Chilango magazine that in Juárez, 30 percent of housing is occupied by Airbnb — by people who “don’t identify with the barrio . . . [who] aren’t strengthening the social fabric.”

With more tourists, the compositions of the neighborhoods are altered. Restaurants start to provide food according to visitors’ tastes, and the types of shops change. Critics of the impact of Airbnb in other cities have labeled this process “Disneyfication.” And while rents increase in the nice inner-city areas, Mexicans are having to live further and further away.

“Those who are displaced by Airbnb usually do pay taxes and they contribute in a lot of ways to the creation of the city and its barrios,” 06000 Observa told Truthout. “In the historic center, it’s sad that public resources that have been invested for decades in re-populating the area are now being leveraged for the benefit of tourists rather than residents. How can we ensure that Airbnb doesn’t contribute to the segregation of a city?”

Much of the housing in Mexico is informal and unregulated, leaving residents particularly vulnerable to earthquakes and issues with utilities and safety. (Tamara Pearson)

Access to housing is already dire in Mexico

According to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everyone has the right to adequate housing conditions, including to protection against forced evictions, security of tenure and non-discriminatory access to housing.

But in Mexico, living conditions are already strained, without taking into consideration companies like Airbnb. On average, homes have one roomper person, compared to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of 1.8 rooms. One in four homes in Mexico don’t have running toilets, compared to 4 percent of homes in OECD countries. For any Mexicans earning less than five times the minimum wage, buying a house is impossible, as housing loans are limited to those earning more than that. That means 74 million Mexicans are excluded from the formal housing market.

However, Loyde believes that it is the “permissiveness of the local government” that has really allowed Airbnb to flourish. Its growth “is taking place with little monitoring,” she said.

In Mexico City, platforms like Airbnb, Booking and HomeAway do incur a 3 percent tax, but 06000 Observa said such a rate is symbolic, and its activists want to see more: “There’s no regulation in Mexico, as there is in other countries, that limits the number of rooms nor the number of days that accommodation can be offered through Airbnb.”

Fostering healthy tourism

Both Loyde and 06000 Observa have inspiring visions of how tourism and housing could change for the better in Mexico. “The state should guarantee housing [access], not just as a space where you sleep, but as a place where you connect with the city,” Loyde said.

“We believe that other platforms and models should be supported. There’s Fairbnb that proposes, for example, a policy of one user to one home in order to avoid these multi-hosts,” 06000 Observa noted.

They also want the use of companies like Airbnb to be strictly regulated, with a limit of 30 percent of each property available on such platforms, “for a limited number of days per year,” and they want each apartment available through Airbnb to be registered.

Mexico City’s historic center is a surreal, chaotic, evocative place that is rich in history, protest, food and commerce. The main Zócalo (square) alone is breathtaking in its size, with the giant cathedral to one side, the ruins of the main Mexica temple next to it, and the presidential palace next to that.

“Every historic event, every war, has had important incidents in this area,” 06000 Observa told Truthout.

“It’s inevitable that it will be a tourist attraction . . . so what would we ask of tourists? That they . . . be responsible and aware of the delicate ecosystem that they are passing through. That they buy from local businesses and historic businesses . . . and avoid franchises like McDonald’s. That they research the area they are staying in and make sure their comfortable accommodation doesn’t come at the price of someone else’s housing . . . That they understand that their presence here doesn’t necessarily benefit us even if they spend money,” 06000 Observa concluded.

Copyright © Truthout. Reprinted with permission.

Shares