While we wring our hands over Trump’s subversion of the rule of law, the great national unraveling continues. The country teeters on recession. The factories he promised to save shutter and farms that were thriving when he took office face foreclosure.

Almost twenty years of a robo-war on terrorism and obscene tax cuts for the wealthy have left us deeply in debt even as our basic physical infrastructure fell into a state of disrepair. Public libraries have become a bellwether for our empire in decline, as a lack of social services has led to many libraries becoming de facto social agencies. But librarians are not trained as social workers, and many have come to suffer invective and even violence that they don’t deserve and never asked for.

Deeper Than Tick Tock Politics

So, it’s not just the things the Trump junta is doing, but what needs doing and is not getting done on Main Street. A nation as large as ours does not just fall in its capital and the decline that precedes its collapse is not easily evident in four-year election cycles.

By the same indicia we apply to the rest of the world’s nations we are in trouble — but our national hubris blinds us to the warning signs all around us.

The U.S. Census’s latest American Community Survey documents that wealth inequality, as measured by the gap between the nation’s poorest and wealthiest households, is the widest it’s ever been in the last half-a-century.

Meanwhile, the average life expectancy for Americans is on the decline for the third year in a row — the first time that has happened since World War I.

The Slide Is Wide And Local

The rate of suicide spiked by 33 percent for ages 15 to 64 between 1999 and 2016, to a level not seen since World War II. The rate of suicide for young Americans 15 to 24 years of age jumped 30 percent between 2000 and 2017.

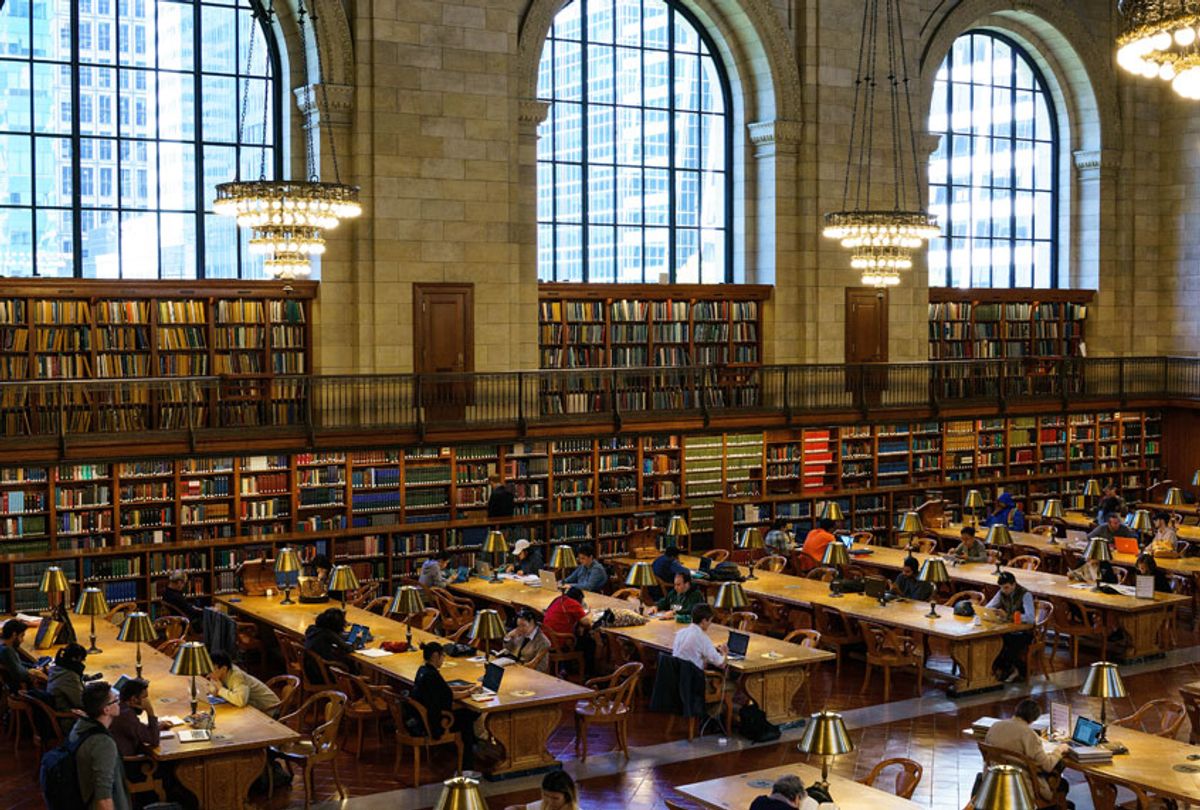

While all the TV cameras are set up for live shots in the marble hallways of our nation’s Capitol, the story that is being missed is the misery playing out at our local public libraries where as many as an estimated two million homeless Americans spend some major portion of their day.

In and amongst this marginalized population, are people contending with all manner of serious mental illness and addiction issues. For them, the public library represents a sanctuary from the vagaries of the street and the hard edges of incarceration.

“Library workers frequently find themselves dealing with patrons who have fallen through the cracks in an increasingly inadequate social services system,” reports HealthDay, in an article titled “Librarians Under Siege.” “Patrons may use the bathrooms to wash clothes and clean up, and they often sleep for hours at crowded tables. Workers are often cursed at and physically threatened by patrons. Conflicts can crop up about overdue book fines and Internet rooms and computers.”

The Power Of Film

This national phenomenon is poignantly depicted in Emilio Estevez’s 2018 film “The Public” set in a Cincinnati, Ohio public library. Estevez plays the local librarian caught up in the midst of a confrontation between the local police and the homeless patrons who seized the library as winter temperatures plummeted.

In an April interview about the film Ryan Dowd, author of “The Librarian’s Guide to Homelessness: An Empathy Driven Approach to Solving Problems, Preventing Conflict, and Serving Everyone” explained why libraries are now the epicenter for the homeless crisis.

“Libraries are everything that homeless shelters are not,” said Dowd. “They’re not as crowded, not as loud. I run a homeless shelter, but they’re not a great place to be, particularly if you’re struggling with autism or mental health issues.”

He continued, “So, libraries can be a refuge from the chaos of homelessness. It’s not just the heat, it’s not just the fact you can charge your cellphone there — but an opportunity to get away from homelessness for a little while.”

Letting our public libraries become the de facto community based mental health centers has already had dangerous and deadly consequences. Just type in “assaults” and “librarians” in Google.

Deadly Consequences

In January, Dr. Leroy Hommerding, 69, the director of the Fort Myers Beach Public Library, in Florida was fatally stabbed as he opened the doors for a weekend book sale. Police arrested a 36-year-old man that witnesses and library workers said was homeless.

Dr. Hommerding was considered the driving force behind the community public library. The suspect, who slept in a nearby old vacant Topps Supermarket, had stabbed another homeless man ten days earlier, and said that the librarian had “disrespected him.”

Press reports described the librarian as someone who was compassionate and worked with the homeless population. He was not quick to resort to calling the police but strived to insure all of the library patrons felt safe and respected. Last month the Florida courts found his murderer mentally unfit to stand trial.

The Island Sand Paper editorialized about the “significant homeless population” in the Lee County, Fort Meyers Beach area but wisely warned against directing “the cops to go from bridge to bridge, rousting all the homeless off our island” rightly observing it would not “fix” the nuanced problem that’s at the intersection of homelessness and mental illness.

“Communities can provide food and shelter, but until mental health is addressed, and treatment options exist, we’re just spinning our wheels. Our culture still refuses to recognize mental illness as being as valid as physical illness. Many health plans limit care. The stigma of mental illness is a huge barrier to seeking treatment. So long as that is true, how can we expect those who suffer from mental illness to seek care and learn to manage it?”

Good Intentions?

Decades ago, I remember the public policy debate sparked by breakthrough investigative reporting on how abusive and cruel state psychiatric facilities were for people with severe mental illness.

Across the country, state legislatures and the courts all responded as the nation embarked on a policy to de-institutionalize the mentally ill with the articulated policy that instead we would create neighborhood-based facilities.

That never really happened.

In an Oct. 2013 article for the AMA Journal of Ethics, Dr. Daniel Yohanna brilliantly captures the arc of this rolling tragedy that plays out across the nation with all sorts of terrible consequences.

“These court decisions have certainly limited the ability of state facilities to confine people in hospitals against their will and created conflict between laws that are intended to preserve liberty and prevent wrongful hospitalization, on the one hand, and the need to identify and treat people early in their diseases, on the other,” Yohanna wrote.

He continued, “The changes that led to this lack of space, as well as changes to the institutionalization process, have made it impossible for people with severe mental illness to find appropriate care and shelter, resulting in homelessness or “housing” in the criminal justice system’s jails and prisons.”

Jail As Asylum

Back in 2010 when there were 2,361,123 people in American prisons experts estimated that nearly 378,000 incarcerated persons had a severe mental illness.

I have chronicled the toll this lack of a humane societal response has taken, not only on the mentally ill homeless, but on the workforce they encounter: public transit workers, emergency medical staff and corrections officers.

By September 2016 things had gotten even more acute in the nation’s jails.

“Serious mental illness has become so prevalent in the US corrections system that jails and prisons are now commonly called ‘the new asylums,’” according to a white paper by the Treatment Advocacy Center, a non-profit advocacy group. “In point of fact, the Los Angeles County Jail, Chicago’s Cook County Jail, or New York’s Riker’s Island Jail each hold more mentally ill inmates than any remaining psychiatric hospital in the United States. Overall, approximately 20 percent of inmates in jails and fifteen of inmates in state prisons are now estimated to have a serious mental illness….. nearly 10 times the number of patients remaining in the nation’s state hospitals.”

Well, there is always our local public library.

Shares