The Supreme Court begins its annual session on Oct. 7 and will take up a series of cases likely to have political reverberations in the 2020 elections.

Major cases this year address the immigration program for young people (“Dreamers”) known as DACA, the Affordable Care Act (again), and public money for religious schools.

Justices will also consider cases that involve several aspects of defendants’ rights: whether criminal convictions require a unanimous jury, minors can be given a life sentence and a state can abolish the insanity defense.

Some of the most important rulings will address the recognition of rights by the conservative court: gay rights, gun rights and Native rights.

These cases focus on perhaps the deepest divide on the court: Should the justices base their rulings on the contemporary meaning of words in our laws (or in the Constitution itself) as the public understanding of those concepts changes over time?

Or should they insist that our laws can only be changed from their original meaning by the country’s democratic representatives, who are directly accountable to the people?

Gay rights

The justices will consider three cases on LGBT employment rights.

Gerald Bostock was fired by Clayton County, Georgia, because he is gay. Donald Zarda was fired from his job as a tandem sky-dive instructor for being gay (before his death in a BASE-jumping accident). Aimee Stephens transitioned from male to female identity and was fired from her job as a funeral director.

These cases turn on one word’s meaning: the word “sex” in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Does “sex” mean what legislators thought it meant when the law was passed, barring discrimination against women? Or should it be interpreted more broadly now to mean discrimination against any aspect of sexuality?

Gun rights

It has been almost a decade since the court recognized a fundamental right for individual citizens to bear arms. That case was MacDonald v. Chicago, from the city with the highest total number of gun deaths in the nation.

Since that time, the looming question has been what sort of restrictions would be considered constitutional.

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. New York City puts this question to the test. Licensed gun owners were prevented from transporting firearms outside of their homes, even to a second home or to a shooting competition outside the city. The court must decide if this is a reasonable regulation that leaves the essential right to bear arms intact.

In the midst of growing concern over mass shootings, the ruling may have ramifications for future attempts at gun regulations.

To raise the political stakes even further, five U.S. senators in their now infamous “enemy-of-the-Court” brief threaten that if the court does not dismiss the case, the Senate will have to consider adding more justices to the court in an attempt to shift its partisan balance, known as “packing the Court.”

Native rights

The least-known but potentially most important case of the year is not about widely-discussed gay rights or gun rights, but about Native rights.

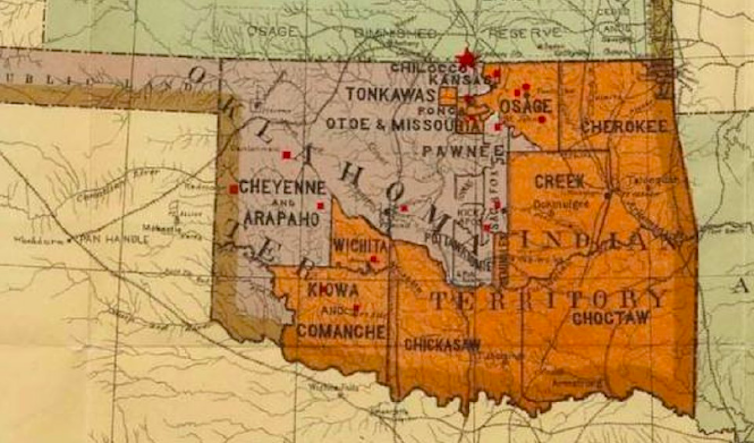

Sharp v. Murphy began as a dispute over jurisdiction in a murder prosecution. But it has become a potentially influential case about who represents the rightful government of Eastern Oklahoma.

The historic reservations of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole Nations comprise 40% of Oklahoma land. These tribes were forcibly removed from the eastern U.S. to the Oklahoma Territory in the 1830s, some making the journey along the infamous Trail of Tears.

Since then, parts of their reservation land have been seized by the state government or sold to private citizens, so they are no longer part of the reservation. This includes the city of Tulsa.

The argument in the case is that according to the original treaties the petitioners are asking the court to uphold, those lands are rightfully still under the government of the tribes. What exactly this means in terms of ownership and governance is unclear.

This may at first appear to be a small case about a piece of the American West. But if the Native rights claim is recognized by the court, it may also apply in later cases to a surprisingly large proportion of the United States that was once “Indian country” under official treaties. That is why 10 states filed a friend-of-the-court brief arguing against the Native rights claim.

Bigger implications

The Native rights claims at issue are not individual rights of the type the U.S. Constitution generally contemplates. They are rights held by an ethnic group. The question of who belongs to the group – and hence has access to the group right – is a divisive one because any answer includes some members while excluding others who claim the same identity.

It also is reminiscent of another proposed group right that is being debated in American politics: reparations. This summer the U.S. Congress held contentious hearings to discuss possible payments as reparations for slavery.

But payments to whom? Both Native Americans and African Americans share a distinct problem yet to be solved: how to determine who is a member of the group.

So in the case of reparations: Would they be paid only to direct descendants of slaves? To all African American descendants no matter when their progenitors arrived in the U.S.? To all people who have any black ancestors regardless of their current status or wealth?

Many Native tribes use what’s called the “blood quantum” approach, which forces individuals to document their lineage and proportional ancestry to prove membership. But scholars in this area argue that this approach is fraught with complications in many contexts.

Election 2020

Democratic presidential hopefuls have already grappled with questions around tribal membership and the country’s history of racism. Sen. Elizabeth Warren has dealt with a damaging controversy over her claims to Native American ancestry. Former Vice President Joe Biden has come under fire for his earlier opposition to reparations.

In terms of both legal and political influence, Sharp v. Murphy is a case with potentially major ramifications. And with the combined focus on politically divisive issues like gay rights, gun rights and Native rights, this year’s docket is likely to have an unusually strong presence in the 2020 campaigns.

Morgan Marietta, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Massachusetts Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares