As the leaves begin to turn on the trees, so too will they continue to turn with new and exciting books for the fall. October isn’t just for pumpkin spice but for any range of flavors that could delight the mental palate.

Both Saeed Jones and Liz Phair release memoirs on Oct. 8. “How We Fight for Our Lives” details Jones’ childhood growing up dealing with questions of his sexual identity in Texas, while in “Horror Stories,” feminist rock star Phair traces her key moments in her life. Also being released on this date is Zadie Smith’s collection of 11 short stories, “Grand Union.”

A week later on Oct. 15, comedian Ali Wong’s “Dear Girls: Intimate Tales, Untold Secrets & Advice for Living Your Best Life” will no doubt prove to be simultaneously instructional and hilarious. Also out that day, on the opposite end of the spectrum is Ronan Farrow’s account of violence and espionage in “Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators.”

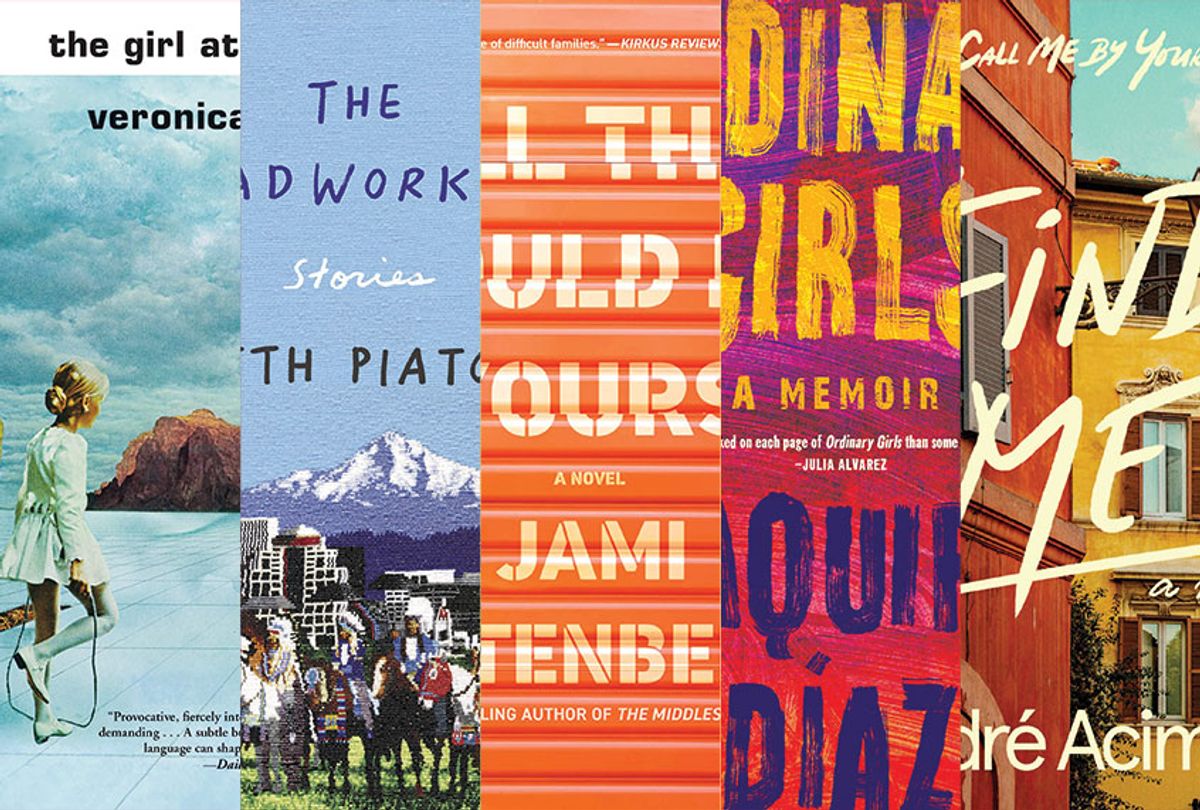

The following five books – four novels and a memoir - range in pace, from electrifying and deft to meandering and meditational. But they all deal with connection - whether it’s romantic, ephemeral, historical, or painfully askew - and the intriguing results.

“Find Me” by André Aciman (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Oct. 29)

In 2017, Luca Guadagnino released “Call Me by Your Name” — or the film that sparked a furious uptick in lusty peach emoji usage. It’s a lush, tender story of first love between 17-year-old Elio and his father’s 24-year-old graduate student, Oliver.

It’s based on the 2007 novel of the same name by André Aciman, which is equally cinematic; and since the film’s release, fans were eager for a second novel (which would, perhaps, lead to a film sequel). When asked about that prospect in 2017, Aciman replied, "the problem with a sequel is that you need plot.”

But in “Find Me,” that much-awaited sequel, Aciman found one that is just as intimate and touching as its predecessor, delicately propelled by a tireless inquiry into the nature and longevity of true love. We open on a familiar character — Samuel, Elio’s father. He’s on a train from Florence to Rome, visiting his son who has become a talented classical pianist.

While traveling, he begins speaking with a bright, young photographer with an acerbic wit. Her name is Miranda and, like Sami, is an American expatriate. She’s much younger than — about half his age, give or take a few years — but their connection is immediate. By the end of the trip, both have variations of the same thought: “I’ve known you for less than an hour on a train. Yet you totally understand me.”

Sami and Miranda are left to figure out if they have a future, and what that would even look like.

Elio has started a new relationship of his own with a Parisian attorney name Michael. It’s a pleasant relationship, but memories of Oliver become more vivid and present with each day that passes.

Meanwhile, Oliver is living in New England. He has a good life; he’s a college professor with a family. But, like Elio, his lingering memories of their affair are increasingly evocative. But will it be enough to cause him to traverse the Atlantic again?

While “Find Me” is very much an exploration of age-old drivers like love, lust and romance, it never falls into cliche. Instead, Aciman deconstructs what makes up our concept of intimacy through his masterful use of emotional nuance and detail, and then builds it back up again — all to a satisfying end. — Ashlie D. Stevens

“Ordinary Girls: A Memoir,” Jaquira Díaz (Algonquin Books, Oct. 29)

There’s a certain ferocity throughout the entirety of “Ordinary Girls.” For some of the book, it’s humming like a hardworking engine — concealed under the hood, always present — but then there are moments when it combusts, bursting from the page in such a way that you, as a reader, have to pause and take a breath.

Like this passage in which Díaz writes about how she and her middle school friends contemplate death:

Some girls took sleeping pills and then called 911, or slit their wrists the wrong way and waited to be found in the bathtub. But we didn’t want to be like those ordinary girls. We wanted to be throttled, mangled, thrown. We wanted the violence. We wanted something we could never come back from.

Ordinary girls didn’t drive their parents’ cars off the Fifth Street Bridge into Biscayne Bay, or jump off the back of a pickup in the middle of I-95, or set themselves on fire. Ordinary girls didn’t fall from the sky.

This memoir is a story about a young woman caught between worlds: the housing projects of Miami and Puerto Rico; the enduring love of her friends while family is torn apart by her mother’s schizophrenia and her father’s infidelity; her own developing future and the history of colonialism in Puerto Rico.

“Ordinary Girls” is an electrifying, deftly-paced debut. — Ashlie D. Stevens

“All This Could Be Yours” Jami Attenberg (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Oct. 22)

This novel begins with the simple line: “He was an angry man, and he was an ugly man.” Attenberg is writing about Victor Tuchman. Moments later, he collapses. Victor has had a heart attack and his family soon gathers at his bedside in New Orleans. And while the plot of “All This Could Be Yours” only takes place over a single day — albeit a very, very long day — the stories told in the novel encapsulate lifetimes.

We learn about Barbara, Victor’s long-suffering wife. Gary, their son, is not in contact with them as he tries to get his business off the ground in Los Angeles, while his wife Twyla is there in New Orleans, having a series of nervous breakdowns in CVS pharmacies across the city. Then there’s Alex, Gary’s sister. She’s a strong-headed lawyer who wants to piece together why her father, a greedy real-estate developer, was the way he was.

“If I know why they are the way they are, then maybe I can learn why I am the way I am,” she confesses.

Bit by bit, readers put the pieces together, finding where all the characters’ stories — even those of the hospital nurse and drug store clerk — converge. But only time will tell if the characters’ themselves recognize how they are connected. — Ashlie D. Stevens

“The Beadworkers,” stories by Beth Piatote (Counterpoint Press, Oct. 22)

Beth Piatote’s marvelous debut short story collection explores crossroads in the lives of unforgettable Indigenous characters within urban, suburban, rural and reservation settings, both past and present. Ranging in form from straight narrative to verse — her powerful reimagining of “Antigone,” about a Cayuse-Nez Perce family split over the legal and moral claim to ancestral artifacts and remains, closes the collection — “The Beadworkers” is an intricate and poignant set of meditations on how to move forward with identity and hope intact while reconciling with loss, both collective and personal.

Throughout the collection, Piatote balances her characters’ sorrows with wry humor, in particular with “wIndin!” in which Iris, a young woman in Oregon, designs a sardonic interactive board game for Portland’s annual Indian Art Northwest show with the help of her best friend/unrequited love whose future is in motion while she waits to draw the card that will move her forward, as well as in the 1960s-set “Fish Wars,” in which 11-year-old Trudy’s political awakening is foreshadowed by an innocent fascination with Dick Gregory stand-up routines. Others dwell expressly in tragedy, such as the brief and elegiac “The News of the Day,” about two very different young men at university waiting for bad news to reach them as Wounded Knee plays out far away.

At the heart of the collection is “Falling Crows,” in which the Nez Perce family of a young soldier who comes back from the Middle East “with part of himself missing” grapples with dueling layers of mourning and hope. As Joseph’s mother and sister set to work designing new regalia to fit his prosthesis, he persuades his conservationist uncle Silas to share newly discovered secret tapes of their elders speaking their endangered language, which have recently been entrusted to Silas. “To be in danger is to be in a state of perpetual vigilance; it is fight-or-flight every day,” Piatote writes in what can also be read as a theme running throughout the collection. “[Silas] feels the magnitude of treasure in his arms, and the intense pressure of keeping it safe.” — Erin Keane

“The Girl at the Door,” a novel by Veronica Raimo (Black Cat/Grove Atlantic, Oct. 8)

Cancel culture is out of control! moan #MeToo skeptics who might scoff at the rape claim made by the titular character of Veronica Raimo’s compelling novel “The Girl at the Door.” Perhaps they would see this book, which dives headfirst into the ambiguity of a sexual relationship founded on an imbalance of power and its messy fallout, as a vindication of that skepticism. But Raimo’s tight and provocative novel, set in a vaguely Nordic utopia called Miden, avoids easy classification. Instead it uses the form of a sexual misconduct investigation, with expulsion from paradise as the punishment on the table, to explore larger questions about sex, power, and collective responsibility, outside of the usual context of a familiar legal system and cultural conventions.

The titular girl, an unnamed student at the insular nation’s art academy, has claimed that the affair she had with her professor — at whose door she arrives one afternoon, to drop this bombshell on the professor’s pregnant girlfriend — was not consensual rough sex, as he believed, but rather a series of violent rapes. She has filed an official complaint, and now a full committee investigation must now occur.

The quaint little nation, with its arcane community rituals and tightly controlled admissions to preserve the integrity of the founders’ dream, might not be a direct metaphor for an American university, but the parallels are strong, down to the disciplinary review process — not quite a criminal investigation, but not merely an HR matter either — launched by the girl’s complaint. As the investigation unfolds, “The Girl at the Door” peels back the layers of Miden itself, and the more we learn about the idyllic country, the weirder it gets (of course). Both the professor and his girlfriend are outsiders, with desolate homeland prospects thanks to a widespread economic and environmental Crash, upping the stakes of the investigation considerably for themselves and their unborn child.

Alternating between the points of view of the unnamed professor (Him), outraged at what he views as the girl’s duplicity, and his unnamed girlfriend (Her), who is repulsed by the allegations and seething over how her fate is attached to his disgrace, “The Girl at the Door” infuses the painstaking bureaucracy of the internal investigation with a surprising amount of suspense, balancing the petty absurdities of Miden life with the gravity of the alternative that awaits Her if He is found guilty. All of that pays off when Raimo ends the novel with one final decision that yields results that are — almost shockingly, given what comes before — unambiguous in its statement. — Erin Keane

Shares