In 1903, sociologist, historian and writer W.E.B. Du Bois observed that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” That problem remains in the 21st century.

Racism and white supremacy endure because they are a “changing same,” a social and political paradox. Since black people were deemed by white society to be chattel in 17th-century America, and then won their freedom in the 19th and 20th centuries, there has been a great amount of positive change in terms of the written letter of the law and public attitudes along the color line.

Racism has been largely rejected as a public norm in the United States. Black and brown faces are central to global popular culture. Nonwhites hold key positions of power in the United States and other majority white countries. Barack Obama was twice elected president of the United States.

This progress coexists with centuries of racial inequality in the United States (and the West more generally), where black people continue to face systemic, institutional forms of racial disadvantage across almost all areas of society, including the labor market, wealth and income, health care, the environment, criminal justice, education and overall well-being. Such disparities are generally true for other nonwhites as well including Latinos and Hispanics, Native Americans and other indigenous peoples. Contrary to the “model minority” myth, East and South Asians are also damaged by racism and white supremacy in the United States.

As a group white people retain control over every social, political, economic and cultural institution in the United States. As a group, white Americans also benefit from intergenerational unearned advantages and privileges, relative to nonwhite Americans.

What is the state of the color line in the Age of Trump?

New polling from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research shows that an overwhelming percentage of blacks and Latinos report that Donald Trump has made their lives worse. As reported by NBC, the same poll also shows that “about half of all Americans think Trump’s actions have been bad for African Americans, Muslims and women, and slightly more than half say they’ve been bad for Hispanics.”

Other polls show similar findings. For example, Pew’s 2019 “Race in America” study made clear that most Americans believe that Trump has made “race relations” worse.

Unsurprisingly, there is a clear partisan divide on such issues. A majority of Republicans believe that Trump has improved the lives of blacks, Latinos, and women. Democrats have a clearer view of the negative impact of Trump’s policies, behavior and values, overwhelmingly reporting that Trump has hurt women, Latinos, black people and Muslims.

Political scientists and other researchers have shown that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to be racist.

In addition to feelings of racial hostility towards black Americans, Republicans and conservatives are notably hostile toward nonwhite immigrants, Muslims and other groups they deem to be inherently “un-American.”

Racism distorts reality. Despiteoverwhelming and obvious evidence to the contrary, social scientists have shown that a large percentage of white Americans actually believe that “racism” against white people is a bigger problem in America than racial discrimination against black people and other nonwhites. Other research has shown that a majority of Trump’s supporters hold similar beliefs.

The many lies of whiteness helped to elect Donald Trump in 2016. They remain the source of his deep reservoir of support among his overwhelmingly white base of supporters and enablers.

The color line was and remains international: Trumpism is part of a global white racist movement. What has been called the “New Right” is a reactionary, racial-authoritarian international movement, largely driven by white grievance-mongering and a desire to restore what its members view as “the natural order of things”: White people should be forever dominant and in control of the United States and Europe; black and brown people are to be submissive second-class citizens.

In general, the American people acknowledge that racism as an idea, and a vague set of actions and behaviors, is a problem. They share no unified notion, however, about set of public policies might remedy the structural and institutional inequalities caused by racism and white supremacy.

What would anti-racism look like in practice? How does racism hurt people on both sides of the color line? Do black and brown people have an obligation to educate white people about racism — and about how to limit or reduce its harm? Is the language of “white privilege” still useful when discussing racism and white supremacy in post-civil rights America? How are capitalism and racism tied together? How did we end up electing one of the most racist and white supremacist presidents in American history?

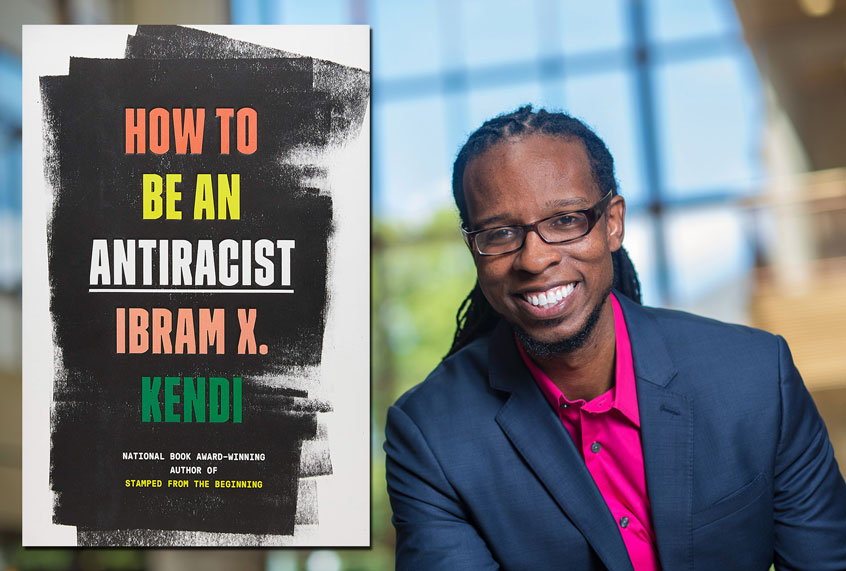

In an effort to answer these questions, I recently spoke with Ibram X. Kendi, a professor of history and international relations and founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University. Kendi is also a 2019 Guggenheim Fellow, and is the author of several books, including the 2016 National Book Award winner “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.” Kendi’s new book is the bestseller “How to Be an Antiracist.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

You are unapologetically committed to telling the truth about racism and white supremacy. How are you able to muster that strength?

For me it is simple. Racism is a problem that’s ravaging humanity. It’s ravaging people all over the globe.

Donald Trump was not elected because of “economic anxiety” among the white working class. The research and other data are clear: Trumpism is white rage in the form of a racist backlash against nonwhites. To suggest otherwise is an assault on the truth. Trumpism is also a moral crisis. That truth must be spoken to as well.

It has always has been a moral crisis. People in positions of power have been supporting policies that are fundamentally immoral. These policies are fundamentally immoral because they are literally harming people. They’re killing people. They’re keeping people in misery. And then these same policymakers try to argue that the misery is not the results of their policies.

Given that Trump and the Republican Party are trying to undo most of the progress of the 20th century in terms of human rights and civil rights, I often find myself wondering, “What year is it?” How do you answer that question for yourself?

What is critical is that we should recognize not only racial progress but to also understand how racism morphs and changes over time. In 2019 there are forms of racism that are more destructive and sophisticated than ever before. We need to focus on both racial progress and racism’s ability to evolve if we are to truly understand what is happening in America and around the world.

What is the very short history of “racism” and “antiracism”?

The term “racism” did not become popular in American scholarly discourse until the 1940s. It is still a relatively new term. But of course, racism as power, policies and ideas is nearly 600 years old. And “antiracism” itself — meaning those who are making the case that there’s nothing wrong with a particular racial group — which means literally creating racial equity, and those movements that are fundamentally challenging racism and its ideas and policies, is also as old as racism itself.

So from the beginning, of course you had enslaved people resisting the slave trade at the ports of Africa and throughout the Middle Passage. There was public and private resistance across the Black Atlantic. It was both violent and nonviolent. Antiracism resistance persists and continue to this very day.

How do you conceptualize the long Black Freedom Struggle?

The Black Freedom Struggle has been a persisting and enduring phenomenon. Within that larger Black Freedom Struggle there have been social movements — and what I mean by social movements are large numbers of black people who, in an organized manner, have effectively challenged racist policies, and to a certain extent, dismantled some of them. These movements have been going on the offensive against racism.

If you want to think about it in a longer view, the most recent part of the Black Freedom Struggle spans from roughly when black people returned from World War I and became “New Negroes.” Some other observers would say that the Black Freedom Struggle began with the NAACP’s successful lawsuits against Jim Crow, beginning in the 1930s. That of course then involved more direct action tactics by the late 1950s.

America has only been a multiracial democracy for 50 years. In many ways, Donald Trump and his movement are a return to the norm.

The emergence of Donald Trump, of course, puts up a mirror to the country’s history that many Americans had thought was resolved by electing a black man, Barack Obama, as president. It forces them to recognize that in many ways Donald Trump and his ideas and his policies are indeed more reflective of the United States presidency than were Barack Obama’s.

I think that’s very difficult for people to accept, but that is the reality. In order for us to create a different type of America where Obama is more representative than Trump, we have to transform systems and policies and ideas in a pretty radical way. This involves not just one person in a particular office. The change needs to be more deep-seated and widespread.

It has been 100 years since the Red Summer of 1919 when white racist mobs rampaged across the United States killing thousands of black people. How are you making sense of that anniversary?

The easiest way for us to understand that relationship is how in many ways Donald Trump is very reflective of someone like Calvin Coolidge, who signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which essentially barred or limited people from every country on earth except so-called Nordic nations of northwestern Europe. Everyone else was considered to be an alien undesirable. And he said America must be kept American.

One hundred years later, Donald Trump is essentially saying the same thing — and they both utilize a tremendous amount of xenophobic and nativist sentiments among white Americans, both in the early part of the 20th and now 21st centuries, to mobilize and organize political support for themselves and to demonize immigrants as the reason why (white) people are struggling, as opposed to their political policies. It was a great bait-and-switch then, and it is a great bait-and-switch now.

It should be surprising to me that in 1919, one of the bestselling books was the racist, eugenicist, nativist tract “The Passing of the Great Race.” Now, in 2019, tens of millions of Americans are yearning for America to be made “great again.”

Donald Trump positioning himself as the next Andrew Jackson also signals to his white supremacist values.

Because Trump and [Steve] Bannon and these right-wing, revanchist nativists, they’re so transparent and honest. I get so frustrated with the mainstream corporate media when they treat anything that this man does as a surprise. He’s telegraphing all his punches. I mean, he’d be the worst, most lazy boxer in the world — don’t use overhand rights, but everybody acts surprised.

When he embraces Andrew Jackson and that version of white populism — hell, Andrew Jackson, never mind genocide against First Nations people — correct me on this history, but I think he was the last president to be a literal slave driver. And they embrace this image of Jackson as this heroic man. It’s right out in front of us.

Several years ago, I wrote an essay ranking the most racist American presidents of all time. Donald Trump actually ranked one step below Andrew Jackson. It did not surprise me one bit that Donald Trump would connect himself with a man who I considered to be the most racist president of all time.

What is gained or lost by using the phrases “black and brown folks” or “people of color” in these conversations about race and inequality?

We should be precise in whatever conversations we are having. So if we’re talking about disparities between all white people and all black people or black people and white people, I don’t have a problem with the use of the term “black people.” But we cannot ignore that, for instance, that there are disparities between African Americans and black immigrants. We can’t ignore that there are disparities between black elites and the black poor, just like there are white elites and people that they call “white trash.” Disparities within the larger racial group should not be ignored.

Then, when we talk about those disparities, we of course have to use specific language to talk about how the racism that African Americans are facing is in some ways distinct from the forms of racism that black immigrants are facing. Or the way in which black poor communities are subjected to the intersection of policies stemming from both racism and capitalism that are not affecting black upper-income people as severely. In total, we must also be very precise in terms of the group we’re referring to and the specific policies we’re discussing.

How can we do a better job of talking about the intersection of this version of capitalism with racism and white supremacy?

In “How to Be an Antiracist,” I identify racism and capitalism as “the conjoined twins.” They essentially have the same body with different faces and different personalities. Because when you really look at the history of racism, it cannot be properly understood without grappling with the history of capitalism. The history of capitalism cannot be properly understood without understanding the history of racism. Racism and capitalism emerged simultaneously, they have grown together, they have ravaged together — and one day they’ll ultimately die together.

The term “racial capitalism” — which is essentially this fusion of racism and capitalism — is a more effective way for us to understand those dynamics, those forces of history. I think the term “conjoined twins” allows for the recognition of racism and capitalism essentially being so closely tied together, No. 1 and No. 2.

That is very dangerous thinking because in America the civil religion is capitalism. Too many people confuse “capitalism” and “democracy.” You are introducing the relationship between racism and capitalism, which is even more challenging for many people — and not just to reactionaries or conservatives.

It is dangerous thinking. What is dangerous is how there are so many Americans who say that they’re not racist. But then you ask them to define the term “racist,” they cannot provide a definition. You have so many Americans who swear that they support capitalism, but then when you ask them to define “capitalism,” they have no definition — or they use a definition that is actually not the material reality of how capitalism functions. They talk about a system with markets, a system with competition, a system of buying and selling goods, a system in which businesses are operating for profit. They imagine that is what capitalism is.

Or they try to define capitalism by comparing it to communism or socialism. These common definitions of capitalism do not actually reflect what capitalism is in practice. For a person even to suggest that markets have been free, or to say that the competition between individuals and classes and even nations has been equal, is to completely not understand the reality of how capitalism functions.

“Reverse racism” is another nonsense term in post-civil rights-era America.

It persists because those who use it are not positioning the conversation in inequity. When the conversation is approached from what is commonly considered to be “discrimination,” as opposed to outcomes, the framing is totally different. For example, consider affirmative action policies. Detractors begin with how admissions factors are “race neutral.” Then affirmative action is depicted as somehow unfairly benefiting people of color. That formulation would lead many people to believe that affirmative action is discriminating against white people. Why? Because it is commonly thought that racial discrimination is a pejorative thing. It is bad. Essentially affirmative action is “reverse racism” or “discrimination,” from that point of view.

But what if we had a conversation that is rooted in inequities and then we assess policies based on those criteria? From that premise and framework, a reasonable person cannot look at affirmative action programs and say that they are racist because the goal of such programs is to reduce racial inequity.

We should actually rethink the term “discrimination” itself. Instead of using the term “racial discrimination” and saying that that is fundamentally bad, we should actually use the terms “racist” and “antiracist discrimination.”

For example, let’s say you have a lily-white classroom and the policies allowing that lily-white classroom to stay lily-white involves continuously barring black people at the door. We should call that policy and discriminatory action “racist.”

By comparison, when you have a lily-white classroom with a fixed number of seats and you have a policy that effectively bars or reduces the number of white people entering the room until you get to a more equitable and representative number of people in that room, to me that’s antiracist. That is a policy that leads to equity.

Language is very important. By using the term “discrimination,” it has really created an entry point for racial reactionaries and other conservatives to create this fiction of “reverse discrimination.”

Is “white privilege” a useful term? Some critical race theorists as well as antiracist activists prefer the language of “unearned white advantages.” How have you resolved that tension?

I believe that “white privilege” is a useful term, specifically when it’s used appropriately. Do I think that, for instance, there is such a thing as the white privilege of life? Yes. The data shows, for example, that if you are white, you are likely to live several years longer in the United States.

The reasons why are a different conversation. If you own a home in a neighborhood that is overwhelmingly white, there is an advantage in terms of how much the home will increase in value in a racist society. That is a type of white privilege. When you are holding a gun and a police officer approaches you, is the police officer less likely to execute you? Yes. There are indeed white privileges. But then again, I also think there are ways in which “black elites” have privilege, men have privilege, and heterosexuals and other in-groups have privilege. We should also recognize those privileges as well.

How do questions about “representation” play into these discussions about “antiracism” and “racism”?

“Diversity” and “inclusion” and “representation” are a bit different than the striving to be antiracist. An antiracist is more concerned with getting a person who is striving to be antiracist in a position of power than they are with getting a person of a particular race in a position of power. Just because a person is black does not mean they are going to support antiracist policies. It just means that you’re black.

If you put a person — regardless of their skin color — who is going to support antiracist policies in a position of power, then it is more likely that there will be better “diversity” and “representation.” In that way, “representation” is the effect or the result of antiracist work. It is not the starter.

What is “antiracism”? How do we articulate it as a set of principles and practices?

In terms of principles, antiracism is the recognition that there is nothing wrong or right with any racial group. And when I say, “racial group,” I am not just talking about black people or Asian people or Native peoples. Black women are a racial group. Latinx immigrants are a racial group. As such, there is nothing inherently wrong or right about any racial groups.

The principle here is that an antiracist is not going to denigrate or even lift up any racial group. And because there’s nothing inferior or superior about any racial group, inequities in our society must be the result of racist policies that are being supported by racist power structures and institutions or racist policymakers.

We should challenge racist power, remove racist power, and then replace racist power with antiracist power.

Racism is absurd. Race as a concept is also absurd. But in the United States, we are living in a moment when even the Ku Klux Klan claims that it is not “racist.” Donald Trump is an obvious, transparent, bonafide racist and white supremacist. Yet, he claims to not have a “racist bone” in his body. How do we ameliorate racial inequality when even the most obvious racists and white supremacists claim to not be “racist”?

What’s absolutely critical is that we should stop using the phrase and broader language of “not racist.” We should stop saying, “I’m not racist,” because when you use that term as someone who is opposed to Trump, and as someone who is opposed to white supremacy, you are opening the door to allowing them to use that term.

That is indicative of what racists have always done. So when the language of “racist” or “racism” emerged in the 1940s to describe eugenicists they responded, “I’m not racist. This is science that black people are genetically inferior.” During the fight against Jim Crow segregation, white racists said, “I’m not racist.” And now, in the post-civil rights era and the Age of Trump, white supremacists are saying, “I’m not racist.”

Instead of using the language of “I’m not a racist” the framing should be about antiracism. None of these real racists are saying that they are antiracists. That is how they should be challenged.

There are many well-intentioned white people who ask random black people — or perhaps even black people who study these questions and topics — what they should do to fight racism. In that moment, when a well-intentioned white person asks a black person for guidance about fighting racism, how do you suggest we as black folks should respond?

One of the reasons why I wrote “How to Be an Antiracist” is so I can just refer them to the book or some other expert on the topic.

I specifically refer people to the work of people who are writing on these issues because there needs to be a recognition that there are such things as experts, that there are people where these questions about racism and politics and power are their primary areas of study.

That is not the expertise of every individual black person. Most black people are trying to go about and live their lives. To be happy. Of course, black people are more knowledgeable about racism than white people, because they must face it as part of day-to-day life. Some black folks are trying to understand what they’re facing. But even regular black folks are not necessarily experts who can explain all the complexities of racism.

What about those instances, very often online, where white folks reach out to a black person and basically demand that the latter teach them about racism?

We need to have a serious conversation about the emotional labor and stress that black folks and brown folks, but especially black folks, are suffering under racism. But somehow we’re also expected to educate other folks about what they should be doing as moral human beings.

I actually tell and encourage people of color first and foremost that it is not necessarily your responsibility to teach anyone about racism. This is especially true if that’s not your job or career.

Now, if a black person chooses to do that work based on their knowledge, I suggest that they focus on those white people who are open-minded, who are not going to cause us to have a very difficult experience when we’re essentially trying to talk to them about these issues. These white folks should also not be resistant. They should also not be defensive. They should be open-minded. Once they start being defensive, resisting or being argumentative, that is the time for us to walk away. If people are close-minded, it is a waste of our time trying to teach them anyway.

In this moment under Donald Trump’s presidency, what is your greatest fear? And what is your greatest hope?

I think my greatest fear in this moment is that the white supremacist movement in this country will continue to organize itself and amass even more power. That’s not just Trump being re-elected and his maintaining control over the Senate, but also Trumpian Republicans maintaining or even growing control in certain states through continued voter suppression and mass manipulation of white working-class people into believing that the problem is Latinx people. Trump’s white voters will continue to struggle under his presidency. As their struggles grow deeper because of Trumpian public policies, their anger toward people of color will only grow. As a result, mass murders and mass shootings will only increase as well. That is my fear.

My hope is that the antiracist movement in this country will help Trump’s people and others to see what is really happening which is how the public policies they support — and not nonwhite people — are actually causing them harm. I also hope that people who are antiracist will get into positions of power at a federal level, and also at the local level, and then put into place policies that allow democracy to exist and thrive.

This would allow for more equal opportunity. Such an outcome would also allow for white people and others who are hurting to receive a better life. That in turn eliminates the likelihood that they are going to consume racist ideas and then mass murder people.