James Reston, Jr. took leave from teaching during the summer of 1973 to witness the Senate Watergate Committee hearings as he worked with his coauthor on what became the first full‑length book to advocate for Richard Nixon's impeachment. During the following summer, he returned to Washington, D.C., to witness the final act of the impeachment drama, attending the Watergate trials, Supreme Court deliberations over executive privilege, House Judiciary Committee hearings to consider and eventually vote on articles of impeachment, and press briefings at the White House after the release of the “smoking gun” tape.

The following are several entries from "The Impeachment Diary" (Arcade Publishing, October 2019), the almost daily chronicle that Reston kept of those heady, uncertain times, when a president, having been investigated by a special counsel and Congress, was called to account for acts contrary to his oath and office, and fundamental questions about the Constitution were engaged.

July 23, 1974

A satisfying afternoon. I went to the House for credentials to attend the televised Judiciary debate, which begins tomorrow. Outside the House chambers, I sent a page in to ask Representative Bill Steiger, Republican of Wisconsin, to come out. (He was my older brother’s roommate at the University of Wisconsin and a very thoughtful guy.) In a fifteen-minute chat, he complained that the press was not giving enough attention to the individual conscience of each congressman. “They’re always looking for a political or self-serving motive from a politician.”

The pack then scrambled to the press conference of Lawrence Hogan (Republican from Maryland). It was as if Bill Steiger had intuited the importance. Hogan began discursively. Impeachment is a “quasi-criminal procedure that requires the highest standard of proof, proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

“After having read and reread, sifted and tested the mass of information which came before us, I have come to the conclusion that Richard M. Nixon has, beyond a reasonable doubt, committed impeachable offenses, which, in my judgment, are of sufficient magnitude that he should be removed from office. The president has lied repeatedly, deceiving public officials and the American people. He has withheld information necessary for our system of justice to work. Instead of cooperating with prosecutors and investigators, he concealed and covered up evidence and coached witnesses, so that their testimony would show things that were not true. He approved the payment of what he knew to be blackmail to buy silence of an important Watergate witness. He praised and rewarded those who he knew had committed perjury. He participated in a conspiracy to obstruct justice.”

I stood aghast. Was I really watching this? I had goose bumps. He went on:

“Clearly, this is an occasion when party loyalty demands too much. To base this decision on politics would not only violate my own conscience, but would be a breach of my oath of office to uphold the Constitution. Those who oppose impeachment say it would weaken the presidency. In my view, if we do not impeach this president after all that he has done, we would be weakening the presidency even more.”

So he is the first Republican. How many more will there be? In questioning after his statement, Hogan predicted that at least five and possibly eight of the seventeen members of the committee would vote yea. Inevitably, the cynics among the reporters were speculating about ulterior motives. Wasn’t Hogan running for governor of Maryland? The Baltimore Sun reporter crafted his gotcha: Is Hogan deserting a sinking ship? This implies, of course, that Hogan is a rat.

July 26, 1974

I haven’t entered anything in this diary in the past few days, and it is because I’m overwhelmed by what has happened. Two days ago, the Supreme Court ruled 8–0 that the president must turn over sixty-four tape recordings to the special prosecutor. I was there. Later that evening, the debate on articles of impeachment began in the Judiciary Committee. I watched it, as if it was a night baseball game, at Chuck Morgan’s house on Constitution Avenue over fried chicken and beer. Yesterday, each member had fifteen minutes to speak, and I attended the morning session. Today, with the statements of all members completed, the debate moves to consideration of articles of impeachment.

The papers are full of stories about the dwindling support of the president. On television this morning, congressmen are predicting that seven of the seventeen Republicans on the committee will vote for one or more articles, making the vote 28–10. Half my mind is on the debate as I sit here in my little study with the television on without sound. But I must put down my memories of the past few days before it’s too late. Events are rushing so fast!

On Wednesday I was admitted late to the corridor on the side of the Supreme Court chambers reserved for the press, getting one of the last admission tickets. Authors must take a back seat to the working press, and that’s as it should be. Supporters of both sides mingled outside the courtroom ready to receive their victor after the decision was rendered. Once inside, I watched the decision on tiptoes from the back of the chamber, past heads of well-groomed hair, through a brass grate, and around a post. With all the wrangling for a clear beam, I could see only about half the bench. But what a set! The backdrop of the lovely rich red damask curtain imparts a stateliness. I could see the ceiling best of all: luscious red and blue background for the plaster, flower-like designs. The room is magnificent—what I could see of it. There is something Roman about the scene.

One could feel the excitement of the audience, as there was no certainty how the Court will rule on United States vs. Richard Nixon. But the presence of the special prosecutor at the counsel’s table gave a hint.

The Chief Justice, Warren Burger, a Republican and a Minnesotan appointed by Nixon five years ago, began with a lengthy, convoluted discourse on the jurisdiction of the Court and the law governing subpoenas, Rule 17(c) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, before he addressed the central question. The legalisms, dense as they were, added to the drama. When he finally got to the claim of privilege by the president, the tension was high. I admit I had trouble in following the thicket of his verbiage.

Neither the doctrine of separation of powers, nor the need for confidentiality of high-level communications, can sustain an absolute unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from the judicial process under all circumstances. . . . When privilege depends solely on the broad, undifferentiated claim of public interest in the confidentiality of such conversations, a confrontation of other values arises. Absent a claim of need to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets, we find it difficult to accept the argument that even the very important interest of confidentiality of Presidential communications is significantly diminished by the production of such material in in-camera inspection with all the protection that a District Court will be obliged to provide.

Burger is no tower of lucidity, his opinions notorious for being turgid, making it arduous for the public to parse their meaning. He needs a good editor, but I understood the gist. In short, the presidential privilege of confidentiality is not absolute. It has to be balanced against the overriding dictates of criminal law. In balancing the two competing principles, a president will almost always lose, especially since grand jury deliberations are secret.

Burger concluded: “In this case we must weigh the importance of the general privilege of confidentiality of Presidential communications in performance of his responsibilities against the inroads of such privilege of the fair administration of criminal justice. . . . The generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.”

Then most of all, I understood: “Affirmed.” Unanimous 8–0. What, I wondered, would have been the implications of a narrow loss like 5–3? Would it have encouraged Nixon to resist the decision?

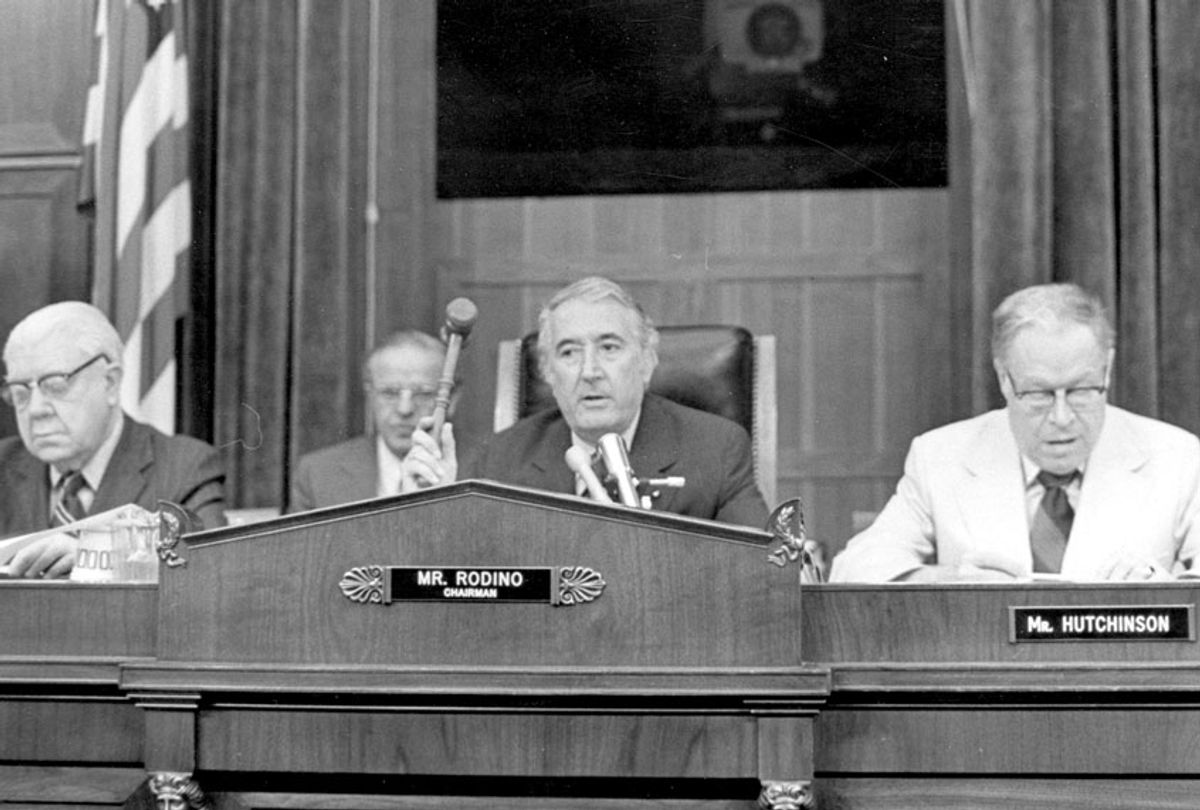

In the hallway afterward, I joined the cluster of people around Jaworski as he answered questions. The answer I remember best is, “I could not be more pleased if I had written the decision myself.” It was, he said, as historic a decision as the Supreme Court has ever made. After the reporters’ questions dwindled, he tarried in the hallway, leaning against a column, signing autographs on visitors’ entry cards like a Broadway star, patiently enjoying it. I had imagined a short man like Rodino, who is only five three, but Jaworski is tall, well over six feet, and speaks in dignified Texas tones.

He then strode out onto the steps, where a throng of about five hundred people greeted him with cheers and shouts of congratulation. The scene was astonishing. Here was the prosecutor of the president of the United States receiving ecstatic jubilation from a crowd of ordinary Americans. What a time this is!

Later in the afternoon came the flash that the president would have a statement at 7:00 p.m. Will he resign? What could be a better time? He could say, “I will not be the president to breach the confidentiality of the Oval Office” and depart on a technical issue. Would he ever have another chance to leave on a more-or-less dignified note? Surely not after the Judiciary Committee recommends impeachment, if it does, or if the full House votes for it, if it will, since that would be an admission of guilt.

At 7:00 p.m., James St. Clair simply announced that the president would comply fully with the Court’s decision. It was a bland, straightforward announcement, something of an anticlimax after so much presidential brinksmanship as to whether he would obey a “definitive” decision. (I think again of Philip Roth’s joke.) How exemplary of Washington’s culture of obfuscation is Nixon’s pale response to the decision later. “I am gratified to note that the Court reaffirmed both the validity and the importance of the principle of executive privilege, the principle I had sought to maintain.”

The important point is that the decision was not only definitive but unanimous. Together with Hogan’s defection and the Republican colleagues who will probably follow him, we’re entering the final act of the king’s dethroning. The king? The potentate? The imperial president? I like best the language of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts during the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson:

“He once declared himself to be the Moses of the colored people. Behold him now, the Pharaoh. With such treachery in such a cause there can be no parley. . . . Pharaoh is at the bar of the Senate for judgment.”

July 27, 1974

And so on to the debate. This will be its third day, and some think its last. Near midnight last night the first symbolic vote was taken in the Judiciary Committee on a motion to strike the first article against the president: “making false or misleading statements to lawfully authorized investigative officers and employees of the United States.” It lost 27 to 11 and thus will stand as Article One. I expect that, as in the Senate vote in the Andrew Johnson case, once the first vote is taken and passes, the others will follow quickly in succession with the same result.

I spent the day in the committee room. The room itself is awesome, with its towering ceiling and fine wood paneling and massive seal of the United States on the wall facing the thirty-eight members of the committee, the grand jurors. The floor space, by contrast, is rather small, and there are only fourteen seats for the public. The rest is reserved for the press and staff.

The opening statements of the congressmen were impressive, a fine display of public oratory, as fine as I have ever witnessed. The anguish of the Republican members is palpable and poignant, as many try to rise above a strict partisan view. Some members stuck to the evidence in their speeches, and their grasp of it now is astonishing.

I’m struck again at the wisdom of keeping the early hearings secret. The stage of floundering about for understanding was kept from public view. When these proceedings became open and public, the customary shallowness and flippancy was absent. Members came off not only as deep experts, but as historians and legal scholars and even moral philosophers as well, all very aware of the historic import of their task. They were exhibiting Carlyle’s first test of heroism: sincerity.

As usual, I’m drawn to the occasional literary allusions that are presented. Lawrence Hogan of Maryland, for example, was full of mixed metaphors. He asserted that many Republicans were looking for an “arrow to the heart,” but there was none. The evidence was like a “virus that creeps up on you slowly and gradually, until its obviousness is overwhelming.” Searching for one document or sentence that would do the president in, he said, was like looking at “a mosaic and focusing in on one single tile and saying, I see nothing wrong with that one little piece.”

Conspiracies were not born in sunlight, said William Cohen of Maine. “They are hatched in dark recesses, amid whispers and code words and verbal signals. The footprints of guilt must often be traced with the searchlight of probability.” It was he who took on Morris Udall’s point about circumstantial evidence. Circumstantial evidence, he said, is just as valid as direct evidence; in fact, sometimes it is even stronger evidence. “If you went to sleep at night and the ground was bare, and you woke up with fresh snow on the ground, then certainly you would conclude as a reasonable person that snow had fallen, even though you had not seen it.” John Seiberling of Ohio improved upon the metaphor. “Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.”

The pro-impeachment forces do not have a monopoly on allusions to sunlight. The defenders of the president were not be outdone on this semantic turf. David Dennis of Indiana, one of the president’s staunchest defenders, insisted that someone had to present the case “in the cold light of the judicial day,” and unless there was a legally provable case, the committee ought not to proceed. “Hearsay will not do. Inference upon inference will not do. Prior recorded testimony and other legal proceedings to which the president was not a party will not serve.”

For me, Barbara Jordan of Texas was the most moving. During the past days she has gone twice to the National Archives to read the Constitution in the original. “Today I am an inquisitor,” she began. “My faith in the Constitution is whole. It is complete. It is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” And then she quoted the Federalist Papers, No. 65. “Who can so properly be the inquisitors for the nation as the representatives of the nation themselves.”

As one commentator is saying in the paper this morning, the members finally came down from Olympus. The wrangling began. The interchanges were sharp and often partisan, and at first, focused on narrow and technical issues over the specific wording of the articles. But at last my advocacy for an omnibus article to encompass them all was addressed, though in a different way. The first two articles, obstruction of justice in the cover-up and abuse of power, combine the general with the specific, and so that seems like the best of both worlds. Article One states that the president “made it his policy” to obstruct justice. That violated his oath of office and his duty faithfully to execute the laws. Then it goes on to nine specific points of obstruction.

Should these nine charges be cited chapter and verse, to enable the defendant to understand precisely what he is being charged with? Did not the president have the same rights as a common criminal? asked Sandman of New Jersey. And Wiggins of California keeps insisting that the proposers of Article One should specify when this policy was declared.

At last, five hours into the proceeding, William Hungate, Democrat from Missouri, gave the proceeding a moment of much-needed humor. About the possibility that the president would not understand the general charges against him, Hungate said, “If they don’t understand what we’re talking about now, they don’t know a hawk from a handsaw.” And on the charge that the proposers were piling inference upon inference, he said,

“If a guy brought an elephant through that door, and one of us said, that is an elephant, some of the doubters would say, you know, that is an inference. It could be a mouse with a glandular condition.”

August 5, 1974, 8 p.m.

At six thirty tonight, the phone rang. My dad [New York Times columnist James Reston] was on the line with an excited tone I had rarely heard in my lifetime.

“Turn on the television. He’s going down the drain!”

And so it has broken. In accordance with the Supreme Court decision, the White House has released the transcript of a June 23, 1972, conversation, only five days after the Watergate break‐in, that shows beyond doubt what we have felt all along but have been unable to prove: that Nixon set the cover-up in motion immediately after the break‐in, directly ordering the CIA to inhibit the FBI’s investigation of the break-in. He admits the tape may damage his case. The president pleads that this new revelation be put in perspective of the whole affair. If it is done so, he argued, the public will see that it does not justify his removal from office.

Tomorrow the details will be clearer. Now Charles Wiggins, the president’s most eloquent defender in the House Impeachment Committee, appears on the screen. “This is not the time for the president to gather in the White House with his lawyers to discuss his defense in the Senate. It is the time for him to gather with the vice president, the chief justice, the leaders of the House and Senate to discuss the orderly transition of power from Richard Nixon to Gerald Ford. I have painfully concluded, with deep personal sorrow, that if he does not do so”—his voice broke, and he was silent for a moment—“his administration must be terminated involuntarily. Therefore, I will vote for Article One.”

How I admire Wiggins suddenly. He has been brilliant in his defense, his language elegant, his points telling, his professionalism respected by all. By his efforts, he prodded the Judiciary Committee to make its case firm. And in it all, he too had been deceived. How well I remember him saying not four days ago how proud he would be to be called upon as a defender of the president in a Senate trial.

Other Republican stalwarts on the committee follow Wiggins: Wiley Mayne of Iowa and David Dennis of Indiana. Even tough‐guy Charles Sandman (Republican of New Jersey) comes very close. He is going home to his district to reassess his position. In the Senate, Senator Robert Griffin, the Republican minority whip, urges resignation. Saying this would be not only for his enemies but his closest friends, Nixon should withdraw for political and personal reasons. (The president would lose his handsome pension if he were convicted, he points out.)

Several days ago, I asked Representative Pete McCloskey, an early proponent of impeachment, about this talk that the tide is sweeping inexorably toward impeachment. How did one judge a “tide” inexorably?

“That’s the way it is in politics,” he answered blandly.

Shares