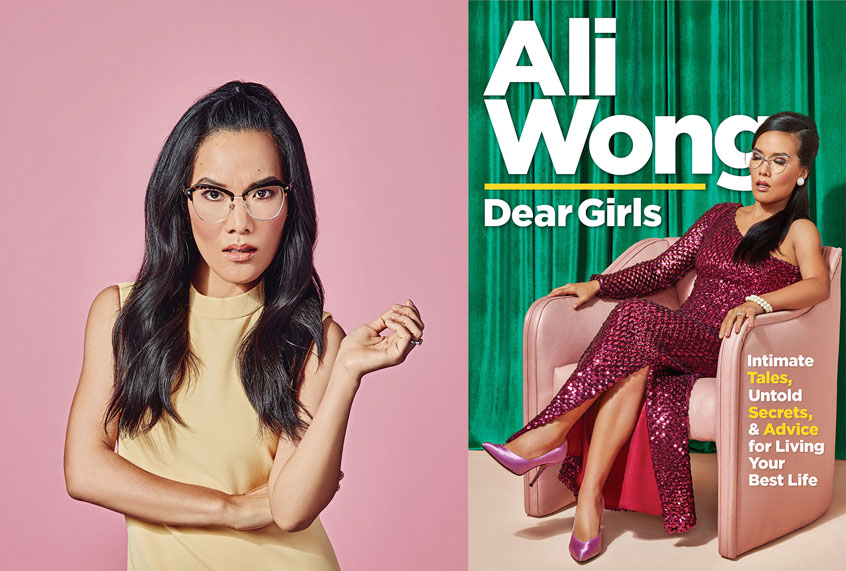

“I’m a f**king idiot,” Ali Wong writes in the preface of her book of essays, “Dear Girls: Intimate Tales, Untold Secrets & Advice for Living Your Best Life.” Don’t be fooled by this self-deprecating declaration even though she is thorough in listing several cringeworthy examples of how she lacks booksmarts. While it’s true that Wong has no concept of how far the moon is from the Earth, she more than makes up for that with a deep insight into what makes her tick and by prioritizing what’s important. And poop. Ali Wong knows poop.

Each chapter begins with the greeting, “Dear girls,” as the comedian addresses her two toddler daughters Mari and Nikki, who are instructed not to read the book until they’re over 21. With titles such as “How I Trapped Your Father” and “Hustle and Pho,” each chapter is an extended essay that reflects on dating, career sacrifices, Asian American identity, motherhood, and other formative life experiences.

This is familiar ground for fans of Wong’s Netflix stand-up specials, “Baby Cobra” and “Hard Knock Wife,” and in that vein, the book does not disappoint. Outrageous, hilarious, and giving absolutely zero f**ks (a trait learned from her late father Adolphus), each meandering anecdote on the page reinforces what the public already knows about Wong. She delivers pop culture specificity and a pungency to her descriptions that make every joke a visceral experience — sometimes uncomfortably so, as she details every gaseous, liquid and solid emission from her various orifices (and those of her husband and children).

But then Wong goes deeper. Each chapter of the deceptively light read begins to have a cumulative effect. Beyond the sexcapades and scatology are stories about self-reflection, family discord and reconciliation, sexism in comedy, and passion. What emerges is a far more complete picture of who Wong is than what she’s portrayed in her stand-up.

She also digs into what shaped her Asian American identity — that doubled-edged sword of wanting to be proud and be counted, and yet not have that define her. For example, she’s thoughtful in how she articulates why her daughters should avoid most of the Disney princess movies except for “Moana”:

White people and stories about white people are not bad, it’s just that when you live in America, everything is so inherently white. I don’t want you to grow up wishing you were white and having that inform all of your decisions later on in life. I want you to be proud of having black hair and Asian features.

It’s a message of empowerment to her daughters, and yet also a message to her readers and fans: Representation matters. An earlier chapter also ties in this idea to why some Asian American women “believe the same stereotypes about us that mainstream America does” and therefore claim they aren’t attracted to Asian American men.

Despite Wong’s pride in all things Asian American, she’s also been careful not to rely too heavily on that humor lest she risk being labeled only as an Asian American comic. Instead, it’s fascinating to read about the path of her career: how a young Wong was inspired by Eddie Murphy’s stand-up and the grueling pace (sometimes up to nine sets in one night) she set for herself when she was coming up in the industry.

Wong writes:

Nobody is great at stand-up comedy right away and it’s important to have room to experiment, find your voice and, most important, to fail … I think all you need to be a good stand-up is to have a unique point of view, be funny, and enjoy bombing in front of strangers. You really do have to learn to like bombing a lot.

Although not explicitly stated, her essays begin to reveal that she uses this philosophy in every aspect of her life. Every ill-advised hookup, every inadequate act of compensation, every selfish thought, every regretful meal that leads to explosive diarrhea, Wong lays bare in celebration. Yes, she took a risk and failed, but then she grew.

Her final chapter titled “Wild Child” is a panorama of bad deeds, as if to scandalize her children while also freeing them from fear of failure or harsh judgment. It’s a final, loving gift to her daughters.

At least, that’s how it seems until the afterword written by Wong’s husband, Justin Hakuta. In this eloquent 16-page chapter, he packs in just as much concentrated history and insight about his family and upbringing. He also gets his chance to tell his side of the story — which Wong had recounted earlier — about how she mooned him and the comedy club audience during one of their first meetings, before they had even started dating.

Hakuta doesn’t attempt any jokes, wisely leaving that to his wife, but he imparts advice that Wong could not: how to live with and support someone who is famous. How he comes to this conclusion somehow transforms everything Wong has revealed in the previous chapters.

“Dear Girls” is more than just a book for Wong’s daughters. It’s also an unexpected, albeit raunchy love story that humanizes Hakuta beyond how he’s treated as the frequent butt of jokes in her stand-up. Offering him the last word allows him to reflect that humanity back on Wong, and that last touch makes the book nothing short of magical.

”Dear Girls: : Intimate Tales, Untold Secrets & Advice for Living Your Best Life” is on sale now from Random House.