It’s no secret that the Democratic Party is undergoing dramatic change. But where, exactly, its future lies remains very much up for grabs, as was vividly illustrated in last week's debate in Ohio. The conventional way to view presidential primary debates is in terms of candidates in a horse race. But the very nature of how the party defines itself is being debated as well. So it helps to step back and think in larger terms. The horse race still matters, surely, and Salon's Amanda Marcotte gave a deft summary of how that went. But former HUD Secretary Julián Castro had a deft summary, too:

Three hours and no questions tonight about climate, housing, or immigration.

Climate change is an existential threat. America has a housing crisis. Children are still in cages at our border.

But you know, Ellen.

Agenda-setting is a core aspect of party definition. Let others do it for you, and they are defining who you are. Redefining the agenda means taking that power back — not just by setting agenda topics, but how they’re presented as well.

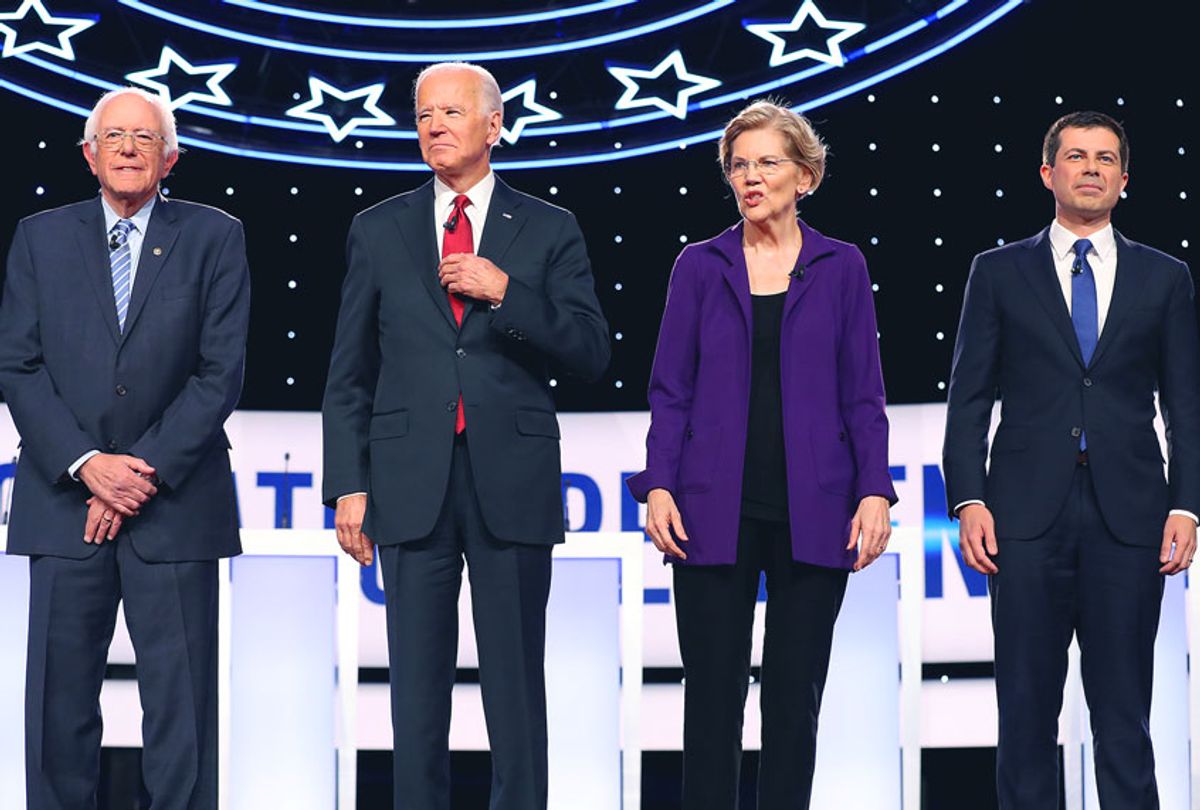

As Marcotte noted, the debate's moderators "kicked off a lengthy health care discussion rooted deeply in the Republican framing about how much we'll have to raise taxes to pay for Medicare for All." Nowhere was it ever even hinted that Medicare for All was the original vision underlying Medicare, introduced by Harry Truman in November 1945. When Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar attack it, they are repeating GOP attacks first launched more than 70 years ago. Despite decades of blather about the “liberal media,” this is just one example of how Republican-friendly framing has dominated political discourse in the media for generations. And part of what’s at stake in the 2020 Democratic primary is the fight to bring that to an end.

Dog-whistle politics has been key to that framing, Ian Haney López told me in my two-part interview (here & here) on his new book, “Merge Left.” It involves three linked messages: “First, fear and resent people of color; second, hate government; third, trust the marketplace,” all for the benefit of greedy elites.

“These two central dynamics, racial division and surging economic inequality, they are flip sides of the same thing, of dog-whistle politics,” López told me. “They are not separate phenomena.” And the best way to fight them is to call them out explicitly, using the "race-class narratives" developed in a partnership between López and communications guru Anat Shenker-Osorio, as I reported last year. López said as much again in a New York Times op-ed just before the most recent debate, but to little avail.

“Without a direct prompt from the moderators, the candidates said nothing of substance about Trump’s racism or government violence against communities of color,” López told me afterwards. “This is an alarm that will be heard most easily by those focused on racial justice. But every progressive should be deeply worried. Stoking racial division has been and remains the most powerful weapon wielded by economic titans and their pocket political party for decades.” It remains so today.

“If Democrats don’t name and defeat this tactic by purposefully building cross-racial solidarity, we will continue to lose on every important issue,” López warned. “We may win some elections, but we won’t win enough political power to enact the bold policies needed to ensure our families a meaningful opportunity to thrive, whether we are white, black or brown.”

The situation is particularly frustrating, given how easily the first steps could be taken. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren were the only two candidates to use the phrase, “middle-class families,” but the research that López and Shenker-Osorio did shows that specifically adding race in such settings increases support among all racial groups, including white people.

On Medicare for All, Warren said, “Costs will go up for the wealthy and for big corporations, and for hard-working middle-class families, costs will go down.” All she needed to do to amplify that was to say, “... for hard-working middle-class families — white, black and brown ... .”

Similarly, Sanders described the bankruptcy bill (co-authored in the Senate by Joe Biden) as “hurting middle-class families all over this country.” Sanders said. He, too, could have simply inserted “white, black and brown” as a small step toward building cross-racial solidarity, and bringing race back into a debate from which the moderator’s questions had virtually excluded it.

This is a responsibility all the Democratic candidates must share, regardless of race or ideological orientation. Even the most "moderate" of those candidates share a belief in government as a force for good, however tepid their version of that may be in practice. They need to say so, not just once or twice, but repeatedly, every chance they get, and say so by explicitly including all races. Criticize one another’s ideas all you want, but don’t use right-wing, anti-government talking points, and make clear that better policies will benefit people of all races. That should be the baseline for any discussion, while also pushing to include issues and questions that are being sidelined, minimized or ignored.

But the racial resentment underlying dog-whistle politics isn’t the only factor framing our politics. As shown in “The Long Southern Strategy” (Salon interview here), gender and religion played key roles as well. Modern sexism — resentment and distrust of women entering "non-traditional roles — was a major factor in Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss, co-author Angie Maxwell told me after the debate. There are various options in how to respond, she said, “all of which were on display” in the varied approaches of the four female presidential candidates.

“One can ignore the modern sexists and appeal to those who do not resent or distrust working and ambitious women,” Maxwell said, citing Kamala Harris presenting herself “as a woman fighting specifically for women,” in a multifaceted way:

She was bold and absolute about women’s reproductive freedom and expressed her indignation and moral outrage over the control that some state governments are trying to exercise over women’s bodies — sacred bodies that create and nurture life. She spoke of her mother who came to America alone at age 19, declined an arranged marriage, and raised two daughters to be anything they dreamed of being. And Harris criticized [Brett] Kavanaugh — who has become a saint to the extreme faction of anti-feminist men and women.

In sharp contrast, “On the opposite end of the spectrum, one can don a traditionally ‘masculine’ energy and, in fact, channel some of that modern sexism,” Maxwell said.

Tulsi Gabbard championed her military career and service (which is, of course, absolutely relevant), but she also attempted to directly question Elizabeth Warren about why she was fit to be commander in chief. To my knowledge, this is the first direct question inquiring as to one of the female candidate’s qualification for that aspect of the job. And it was a woman who asked it.

On reproductive rights, Gabbard was more conservative than Harris, Maxwell noted, identifying her position as similar to Hillary Clinton’s, but then quickly distancing herself from Clinton “on lots of things,” including “claiming that [Gabbard] didn’t think of people as deplorables,” a somewhat odd zigzag strategy given that Clinton isn’t running. “It’s a soft-pedaling of modern sexism and a dose of hawkish, masculine bravado,” Maxwell summarized. “It’s playing the patriarchy’s game so as not to trigger the modern sexist backlash.”

Between those extremes, “somewhere in the middle, is a candidate who is kind of the political version of a girl with a lot of guy friends,” Maxwell said. “She does not act overly feminine or overtly feminist. She is friendly and smart and somewhat funny. This is the archetype best exemplified by Amy Klobuchar in [last week's] debate.”

There’s a certain logic to this approach, particularly in legislative settings like the Senate, where Klobuchar has thrived. “She lets herself be seen as the exception to the rules, so to speak, in the hope that enough exceptions eventually invalidate the rules,” Maxwell explained. “She can be a woman that even those who express modern sexism might like because they don’t connect that distrust and resentment to her specifically — because she doesn’t call them out for it.”

Finally, Maxwell noted the most difficult approach: “Female candidates can sidestep modern sexism by appearing to be — again, for lack of a better term — gender-neutral or gender-invisible. This is somehow avoiding appearing as a ‘woman’ candidate (while, of course, still physically being one).” This was Warren’s approach, which Maxwell rated as “a master class” in this debate, where no one could knock her off her game:

She did not take the bait from Gabbard, never returning to the question and attempting to defend herself as qualified to be commander in chief. She didn’t bite back at Biden when he took credit for her success and then backtracked and told her she did a good job. She didn’t chastise him, nor did she politely make it all OK. She just moved on to bigger issues. She would not engage with Harris on her request that Warren join her in calling for Trump’s Twitter account to be shut down. She just moves on to trust-busting and campaign finance reform and student loan debt and health care costs. She doesn’t even play on motherhood per se, but parenthood. She is teacher and explainer and parent-in-chief. She stays on the issue with such discipline — never taking punches at any of her competitors (rarely mentioning them at all) — that the issues eclipse her gender and deprive modern sexism of the oxygen it needs to burn. This does not exempt her from opposition. But if she can continue in this vein, which, again, takes extraordinary discipline, the opposition will be to her policies, not to her womanhood ... not to her existence.

One can see strengths in all these approaches, some perhaps more attuned to specific arenas. “If Warren or any other woman were to get the nomination, the GOP — particularly Trump’s GOP — will sound that dog whistle,” Maxwell concluded. “Trump’s campaign will do everything it can to portray her as a feminist who cannot be trusted, in order to stir up the anti-feminist base it began cultivating in the late 1970s.” Warren seems best poised to take this on as things stand now, but in the long term, the synergies of all four approaches should prove significantly more powerful than any one of them alone.

The diversity of approaches Maxwell identifies, as well as their coherence, stand in stark contrast to the lack of development in responding to racial dog whistles seen in the Democratic campaign so far. On one level, that’s understandable: every female candidate for every office in the land has to grapple with how to present herself, knowing that some level of modern sexism stands in her way. Confronting racial dog whistles is more about forging cross-racial alliances than drawing on a common identity. But the more challenging it is, the more necessary it becomes.

This brings us to perhaps the most basic challenge of all: Reclaiming the mantle of being “True Americans.” Since the dawn of the Cold War, Republicans have been painted Democrats as seditious and themselves as True Americans. Republicans have stressed this narrative repeatedly, while Democrats seldom argue in such sweeping terms, focusing much more on specific problem-solving instead.

Of course that GOP narrative has always been a lie, but with Donald Trump in the White House betraying everything America is supposed to stand for, there’s never been a better time for a full-throated rebuttal — and more than that, a complete reversal. This was top of mind when I reached out to Shenker-Osorio before the debate. She focused on the issue of impeachment, which turned out to be the first question posed last week in Ohio:

There's an obvious push from the Democratic establishment to pursue the narrowest possible case [for impeachment], focusing just on Ukraine and Trump's public admission of political dealing against a rival. Selecting just this line of impeachment inquiry is both morally wrong and strategically foolish for a would-be presidential frontrunner. Candidates that want to stand out must stand up for democracy itself. And that means calling for a full examination of all of Trump's offenses, from banning people based on religion to torturing young kids who come seeking safety, to fleecing our country for parts to any bidder. Failure to do so is an admission that a future president is at liberty to do these unlawful things, a tacit undermining of the importance of the office they're seeking.

Note that Shenker-Osorio was talking about what the presidential candidates must do to stand out. “An effective impeachment message from candidates must describe the desirable outcome when Congress does their duty and abides by their oath," she said. "People must have a sense that order and normalcy can be restored — that there's an adult in the room who can do right by us.” There needs to be a sober but optimistic and patriotic message, in other words.

“Focusing only on harms and horrors (and there are so so many) reinforces the sense of endless chaos and insecurity,” Shenker-Osorio warned. “To look and seem presidential, candidates must speak on behalf of having a government of, by and for the people, where the person elected to represent us respects this nation and all her people, no exceptions.”

Several candidates got pieces of this message — but only pieces. They were hampered, in part, by the ways the question was customized for them, but also by their own felt needs to make particular points in line with their campaign themes. A greater failing was that Donald Trump virtually disappeared from the debate after that first question was asked. No effort was made to sustain and amplify points made in calling for Trump’s impeachment with other issues as the debate unfolded. There were no narrative arcs seeking to make the points Shenker-Osorio highlighted, stressing what America can and should be, and what we should expect of our leaders.

To underscore what was missing, I could not help but recall the words of legendary Texas congresswoman Barbara Jordan, during the Nixon impeachment process. She began by anchoring herself in the Constitution, first noting that she and people like her had not originally been included:

Earlier today, we heard the beginning of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States: "We, the people." It's a very eloquent beginning. But when that document was completed on the 17th of September in 1787, I was not included in that "We, the people." I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation and court decision, I have finally been included in "We, the people."

Rather than feel bitterness or betrayal at how that original promise had failed to include her, Jordan affirmed it all the more forcefully because of how much struggle was required to make that promise real:

Today I am an inquisitor. An hyperbole would not be fictional and would not overstate the solemnness that I feel right now. My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution.

This is the kind of narrative we need to guide and sustain us. It can be found as well in Langston Hughes’ poem, “Let America Be America Again,” charting a similar arc from margin to center. It begins with four lines of Trumpian longing, before the true narrator’s voice appears, parenthetically objecting, “America never was America to me!” After more than a dozen stanzas it eventuates in affirmation:

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!

Such are the narrative guidelines all Democratic candidates should emulate. Whatever differences they have, they must affirm a common struggle that spans races and generations, advancing toward a promise that only that struggle can fulfill.

Shares