Nancy Pelosi has announced that the House will finally hold a formal vote dictating the rules for the impeachment inquiry, six weeks after it was launched by a whistleblower’s complaint mysteriously withheld from Congress. And on Tuesday, Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman backed up both the initial whistleblower and U.S. diplomat Bill Taylor by testifying that he too was concerned about the Trump administration’s push to use congressionally-allocated military aid to Ukraine to coerce an investigation into Joe Biden.

Congressional Republicans have long since stopped defending Trump on the merits since shortly after the White House released a transcript of a July call between President Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Instead, they’ve sought refuge in increasingly meaningless process arguments. So of course Pelosi agreeing to a formal vote on the rules of impeachment hasn’t stopped Republican complaints about the process. The goalposts will shift once again. No matter what the Democrats agree to, Republicans will complain about procedural unfairness and also refuse to concede the inquiry is legitimate. But how much of Republicans’ unwillingness to hold Trump accountable for his self-dealing is because they're in on it?

On Monday the Washington Post published an interview with a Ukrainian diplomat who claimed to have met with Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., this summer to discuss the baseless conspiracy theory promoted by President Trump that Ukrainian officials had interfered in the 2016 election on behalf of Hillary Clinton.

Johnson reportedly met with Ukrainian diplomat Andrii Telizhenko for at least 30 minutes on Capitol Hill in July, and Telizhenko then met with Johnson’s Senate staff for five additional hours. According to the report, “the discussions focused in part on ‘the DNC issue’ — a reference to his unsubstantiated claim that the Democratic National Committee worked with the Ukrainian government in 2016 to gather incriminating information about then-Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort. Telizhenko said he could not recall the date of the meeting, but a review of his Facebook page revealed a photo of him and Johnson posted on July 11.”

Johnson is a vocal Trump defender who has hounded the inspector general of the intelligence community about investigating media leaks regarding the Ukraine call. He has previously admitted that he was told by Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, that Ukraine needed to "get to the bottom of what happened in 2016" in order to receive military aid.

As Johnson told the Wall Street Journal earlier this month, Sondland told him that he was assured "if President Trump has that confidence" that the Ukrainians would do his bidding "then he'll release the military spending." Now, as the Post points out, Johnson's "knowledge of key events" in the case may "complicate his role as a juror in a trial by the Senate."

Recall that when Johnson was asked about his defense of Trump’s actions, he snapped at the simple question from NBC News’ Chuck Todd and spun out the same deep state conspiracy theory pushed by the likes of Fox News’ Sean Hannity.

Beyond his apparent involvement in Trump’s Ukraine dealings, Johnson is alleged to have benefited from campaign money illegally funneled from Russia via shell corporations owned by the National Rifle Association, which helped him win his tight 2016 race in Wisconsin.

Political action committees for Republican Sens. Mitch McConnell, Marco Rubio and Lindsey Graham reportedly accepted $7.35 million in contributions from a Ukrainian-born oligarch with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin during the 2016 election. McConnell and Graham are co-sponsors of a new resolution condemning the House impeachment inquiry. At least 50 Senate Republicans, several of whom have refused to publicly comment on the growing Ukraine scandal — citing a need to remain impartial for a likely Senate impeachment trial — have already signed onto that bill. The resolution is currently paused in the Senate Rules Committee until the House votes on impeachment rules later this week.

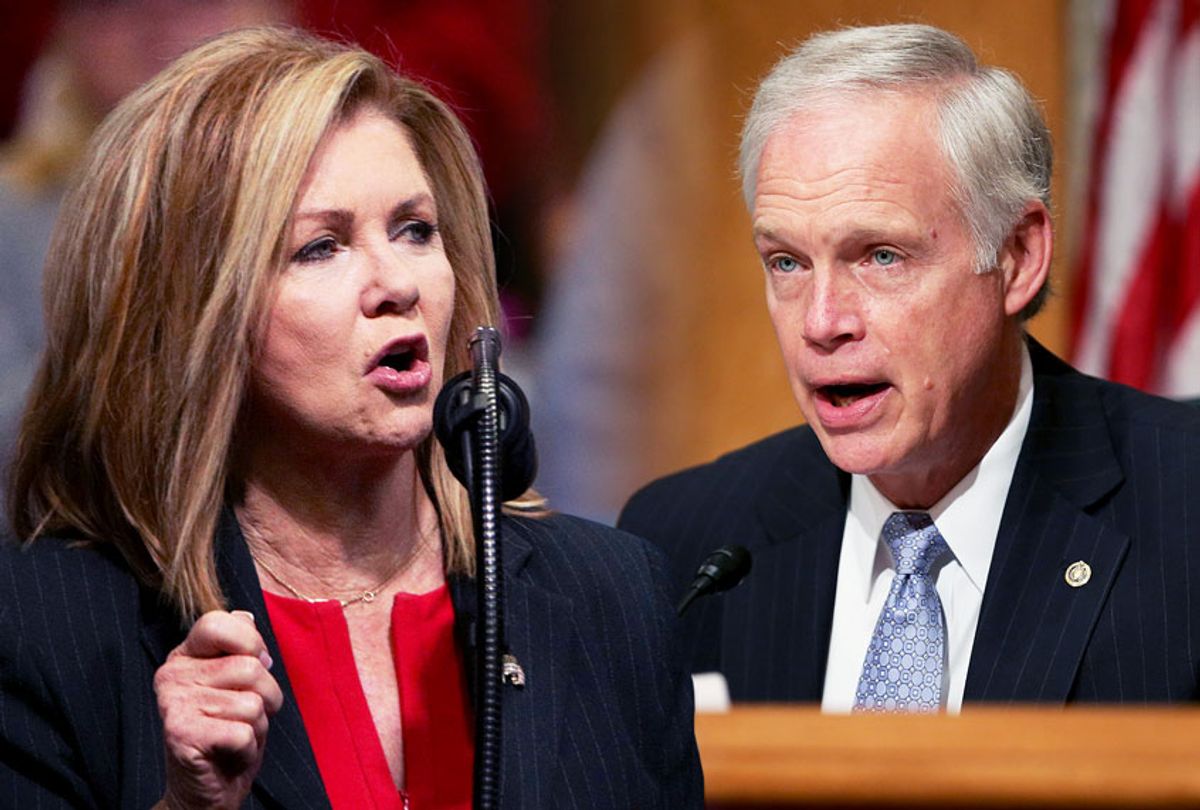

As House Democrats’ investigation has rapidly unveiled ever more damaging material regarding Trump’s Ukraine scandal, public support for impeachment has shot up. Reportedly nervous about his wall of defense in the Senate crumbling, the president hosted several GOP senators at the White House, including Johnson, Graham, John Thune of South Dakota and John Kennedy of Louisiana, last week. A day earlier, Thune and Kennedy, had blocked a Democratic bill to provide funding for states to shore up election security. The next day, Sen. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., quietly blocked three election-security bills for the second time this year.

“You know, it’s not a good sign if you’re doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result," Blackburn said on the Senate floor late last week. She is among the Republican senators with close ties to a U.S.-sanctioned Russian politician who is accused of illegally channeling Russian funds through the NRA. Under Senate rules, any individual senator can block a vote on a bill.

When Senate Republicans are not prematurely dismissing an impeachment inquiry on which they will probably have to render judgment, they continue to protect Trump’s refusal to clamp down on potential election interference. If Republican charges of a "kangaroo court" are anything, they are a classic case of projection: How can Senate Republicans possibly serve as impartial jurors in a trial of the president, when they are implicated in the same pattern of political malfeasance?

Shares