When I was growing up, the older dudes with money who hung around at the basketball courts but didn’t hoop used to send us kids to the store for chips, smokes and beer, and let us keep the change. Between eating their snacks and sipping their beers they would introduce us to the rap artists we should be listening to. Some would push Kool G Rap, while others liked Big Daddy Kane. Above all, Rakim always remained supreme, comfortably resting at the top of everybody’s list.

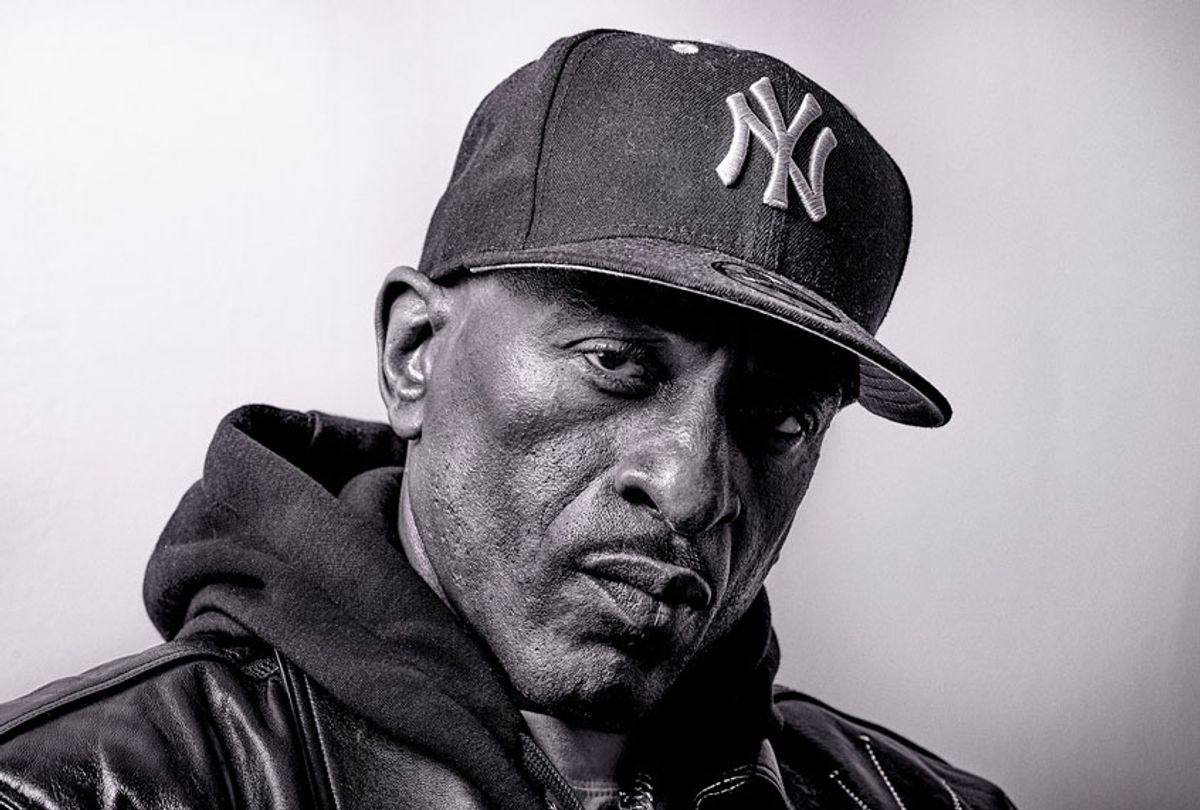

Some of us were too young to comprehend the complex ideas Rakim spat, but his voice and presence drew us all in; we were hooked. The Rakim addiction stretched far past my neighborhood — people felt like this all over the country. The Source magazine named the 51-year-old MC “the greatest lyricist of all time.” Rakim’s early hits still bump in clubs all over the world, and he's still touring after 33 years in the game.

How is this possible when most hip-hop artists fade into obscurity after their first hit, if they are even lucky enough to have a hit at all? Rakim answers this question and many more when we sat down for an episode of “Salon Talks,” in which we discuss his new memoir “Sweat the Technique” and how he has witnessed hip-hop evolve over three decades.

Before Rakim was known for rocking mics, he was a talented saxophonist who studied jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk, both of whom became major influences on his work. As one of hip-hop’s originators, Rakim had to draw from other forms of art for his inspiration, as the genre was still in its developmental stages. In his memoir, Rakim takes us back to his origins in the early hip-hop scene in Wyandanch, Long Island. He talks about his high school football career, the time he mistakenly shot himself at 12, and how the combination of music and family love helped him persevere through all of the negativity that comes with the streets to link up with collaborators Eric B and legendary hip-hop pioneer Marley Marl.

Watch Rakim’s “Salon Talks” episode here, or read the transcript of our conversation below, to hear more about Rakim’s writing process, his future plans and the legendary MCs advice for staying original and true to who you are.

The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I've been spending some time with your new book “Sweat the Technique” over the past few days. You’re written so many lessons in here. It’s a manifesto for a young person coming up, being young and black in America, and just trying to figure out who we are and where we come from. What made you decide to write the book now?

I have always been a little laid back with my personal story and when I write rhymes. It was funny, I never thought I was interesting enough to do a book. But with this book here, I found a way to do a book where instead of it being so much about my life story, I wanted to try to inspire artists in general — if they're rappers, if they paint, whatever they do.

When I read any book, I like to think about if the author had a particular audience in mind. For example, Toni Morrison was read by everybody, but she specifically wrote to and for black people. Do you feel like you had that type of energy when you wrote this?

I wanted to be as universal as possible. Me and my manager, we used to always talk and I used to say, I don't want to just make it for rappers, you know what I mean? I don't want it to be just for hip-hop. I tried to be open minded and think outside of rapping. I didn't want to tunnel-vision a book and again, have it be just be for rappers or just hip-hop. I definitely wanted to try to reach people from all walks.

Most people know you from your music, how you write your rhymes, your delivery and the way your music makes people feel. Writing a book is completely different. What are the differences from your perspective?

One thing about writing a book is you can just slow down and you can just naturally tell your story. You don't have to run. If it's not as entertaining, if it's just a story or just information, it's OK, you know what I mean? I was able to just sit back then and think about why I love music, and more important, what makes me push myself the way I do.

Was it more difficult?

No. We all live in some history. A lot of the personal information hit me as I was reminiscing. On that note, it was rough, but it's much easier than writing a rhyme. It's a lot different and a lot more time consuming. We went through a lot of my history and a lot of my thoughts to come up with those 200-and-something pages right there.

You start off the book writing about your childhood on Long Island. Take us back to Wyandanch and your experience growing up there.

As I look at it, the best way to describe it is, it's one of the places where a village can raise your kid.

Is it still like that?

It’s a little crazy now with the crime going on and it's a lot more separated from when I was there. When I was there coming up, I couldn't walk the street without seeing my mother and father's friends or my brother and sister's friends. If it wasn't them, a teacher might drive by. The town was maybe two miles along, so it was a small, close-knit.

I imagine you had people looking out for you because it was that type of community.

Yes, I was the youngest in my family, so I was Little Griff for 15 or 16 years.

I think people need to understand that this type of neighborhood can exist in America. Regardless of some of the struggles that they go through, we can get back to that because that's the type of communities we need. You write about being exposed to entrepreneurs and doctors and different types of people who were able to live amongst each other in unison and survive like that. And I understand that you come from a musical family.

Yes, sir.

Music is in your bloodline?

Luckily man, my mom, she put it in our genes. She sang everything from jazz to opera and she was really the one that lit the torch for everybody. My oldest brother played the piano. My brother over me played the sax. That's why I used to pick up his sax and play whatever he just played. Both of my sisters sang and one of them played the flute. Coming up it was like, get on the train or get left behind. It was the sax for me and as I was coming up, hip-hop — overnight [it] just took over. And luckily man, I took everything I learned from music and poured it over to hip-hop.

With the explosion of hip-hop and you wanting to be part of the culture, do you feel like that forced you to grow up quick?

No, I think you had to, and I was so young when it was popping off. People in the neighborhood, they had [DJ] equipment. I was in sixth, seventh grade, and the people who had equipment was in high school or college, so in order to get into that crew, you had to step up or at least show them that you was mature enough to hang around. Because for years, I used to hear “Yo, somebody get shorty away from the ropes. Who’s little brother is this?” [Laughs.]

You had to fight to get the microphone?

Yeah, I got turned down plenty of times, but I think mom and pop, they taught me well and taught me values. I think I would have had some morals and things of that nature, but I think hip-hop helped me grow a little faster. Just trying to be a part, trying to keep up with everything. That was going on at a young age.

Can you spend a little bit of time taking about what it was like being in the parks around those times? I grew up in the ‘90s crack era, so by the time I was coming of age if you were in the park, you're either hooping or you’re hitting sales or you’re staying out of the way. When I hear you talk about being in the park, it's this magical place where this music was being birthed.

I remember walking up into the park and immediately I see people playing ball, handball, tennis, and everything, but a bunch of people used to crowd under the hut. The DJ was set up, man, and it was like the 4th of July every night. Me being so in love with music, I guess once I've seen the DJ coming to set up, my mind is turning. I want to rap. It took years before I was able to, but my whole thing was, I used to just get so excited like, "Yo, DJ is coming."

I was such a big fan at the time, I used to sit by the ropes, watch the rapper get on, do his thing or look in the crowd, see who's doing what dances. For me, coming up in that era it was a front row seat to the circus and I just absorbed everything that I could see and start picking up on it. I think that hunger to want to be a part of it at a young age, I think it progressed my pen. It was something that I wanted to do, but nobody would let me do, so I wanted to prove to you all that I'm good enough.

That's why you are so competitive, because you had to fight to get your hands on a microphone. It's not like these days when kids can just jump on YouTube. You had to fight for it.

Yes, you had to go to the source, the party, you know what I mean? If it was in the park, if it was in somebody's backyard or at the school, wherever it was, you had to go there and ask and beg and you’d say to somebody, “Tell the DJ I'm pretty good." Whatever you could do to get on was, by all means.

You started your professional hip-hop career at 17. Do you ever think about if you would've waited and started at a little later, like pursued football in college for a little bit and then got out there in music?

I think it would've been a little different, you know what I mean? It would have been more of, I guess me trying to make it happen at that point, because football didn't happen. It would've been a little different than love. At the point when me and Eric was able to hook up, I thought I was going to go to college, but I was still in love with hip-hop. There was nothing in-between to give me bitter taste about it. It was just, I'm going to write a rhyme. And it wasn't like, well, I've got to write a rhyme, or now this has to work. It was just still love at that point and I think that was the difference.

I can't imagine being on tour at 17.

Yeah, I've got to pat myself on the back again. I salute my mom and pop because there were so many things you can do to get in trouble out there man. At 17, you've got a pocket full of money, whatever you say goes.

Many young people look up to Jordan and Muhammad Ali, but a whole lot of dudes from your neighborhood, from my neighborhood all the way to Baltimore, to my peoples in Philly, all of us looked up to Bruce Lee. Why did Bruce Lee connect with black people so much?

I think it was because we couldn't understand it, you know what I mean? Everything else, we were used to in America. But this brother came from overseas with this brand new fighting style and it was amazing to watch him do his thing and to imagine how small he was, but how nice he was and how confident he was and how mental he was. And that's the thing I got from Bruce Lee later.

At first, I used to watch the movies and go kick at your friend, you know what I mean? Sneak your friend, kick them in the back. But later on I started realizing how mental Bruce was. I started to realize even the most physical sport or the most physical thing acquires thought, mental. I just had that must more respect for him, knowing what drove him to be as great as he was. He just had that passion and that push to get him to where he was.

One reason why I think you always resonate with so many people is because you didn't switch up who you were when you came into the game, even though you were surrounded by legendary people who were encouraging you to change your sound.

Yes, sir.

You also didn't switch up as times changed, or if you did switch, it was just you evolving. Give us some knowledge on that because there’s a lot of people out here who want to do music, or they want to make films, or they want to do these creative things and they try to be something that they're not.

You just hit it on the head. Early, when I was trying to perfect my style, back then there were two ways, well really one, that you could rhyme. There was the high energy stuff.

Like “King of Rock”?

Yeah, man. [Laughs.] I used of run like that in the early days, but as I started maturing or just knowing myself more, I was realizing that I wasn't that high-energy person. I would sit in my room and rhyme, and your moms and pops is in the next room, so you're quiet. I started liking the style that I would use when I was just practicing more than when I would get on the mic and sing. When I practiced it was nice and smooth, laid back. I could fit all the words in. Then you get on the mic and you realize, I put too many words in this rhyme to say it and then I'm losing breath.

These are complex rhymes. I don't even think you can scream them if you want to have the full effect.

Exactly. I started writing with that in mind. I just wanted to be myself as much as possible and create my own style, knowing that I was already a little different. I was always, a little laid back, not so much quiet, but I wasn't a big mouth neither. So just realizing you stand a little more natural when you kick it like this. By the time I got to Marley Marl’s house, I was already convinced, that's not my style. I don't sound good when I rhyme like that. This is my style. I want to perfect this style right here and it's more natural to me and it fits my personality. And I think that was the main thing.

And you’re right, a lot of artists nowadays, either they was influenced by somebody or influenced by whatever they were hearing at the time, and sometimes they get out of themselves and it's hard to get back to yourself once you go down that road. Know who you are and create your style from your personality and who you are and how you see things and how you react to things and how you do things and it'll be more natural and we'll respect you for that originality.

It's a confidence issue. There's so much art in a world that feels the same or looks the same and we get lost in it because people are coming in without confidence.

Yeah, and they're scared to cross that line. I used to always tell people the best thing that an artist can do is be themself. Originality in that person is what makes us drawn to you. If you're going to do the same thing somebody just did, then we’ve just seen that, you know what I mean? We all have something inside of us that separates us from everything. Find that uniqueness in yourself and glorify that—over-exaggerate that and people look twice.

Another writer and I were just talking about growth and how we have evolved over the years and I’ve been thinking about writing versus other professions. For example, me playing basketball now would be destroyed by 17-year-old me — cross me up, step on my head, drag me off the court. But me as a writer now can write circles around everybody I knew at 17. How do you feel as a writer, as an artist and as a lyricist? Do you feel like yourself now is far more superior than your younger self?

Big time. I have a better understanding on life, better understanding on who I am. I am better as a writer and I've got more techniques writing and a lot more knowledge. And then the drive, you know what I mean? Just that extra drive to push yourself further, man. The older we get, the more mature we get, the more we fall in love with our craft, the more it consumes us to the point where that's it, this is who I am. You take on that role and that responsibility.

I can't watch TV without recording mentally. I can't drive down the street, every sign that passes, I've got to read it, a bus passes with a sign and I've got to read it. I don't want to miss nothing. I'm just recording. When I sit down to write and 60 percent of what I may record that week, I may not even use, but it's just constant, just always looking for information and trying to become a better writer. We're at a point where it's a monster and can’t nothing stop it.

Would you teach lyricism at a university, like a special class?

Yeah, I would love to do something like that. My son rhymes and my daughter rhymes too.

The kitchen table battles are probably crazy.

Oh yeah, they go at it. [Laughs.] They don't go at each other but I know they compete with each other. That creative energy, man, they push each other. But I remember days trying to explain to them and just give them all of my little tricks. It's fun because I used to never want to tell nobody what I was doing or what my little tricks were.

You said you didn't even speak to another rapper, you just give him the nod like, yeah, I see you.

Word, stay over there, you know what I mean? I think that was partially the intimidation game, but more than that on a serious side, it was more that I was fresh out the streets and that's the way we did in the streets. People on the other side of the street, you didn't communicate with them. And at the same time, you didn't let nobody too close to your world.

You can't just trust somebody that's friends with everybody from every block and every hood.

Yeah, I kind of brought my street ways into the genre, but it kept me out of a lot of trouble, kept me out of a lot of beef with rappers — even though when I look at it now, it could have caused a lot of beef with rappers. But it was just being me. I ain't disrespect them, but at the same time I wasn't on the friendly, friendly vibe.

This book is the first glimpse that we've had into your personal life ever. The closest second glimpse might have been Nas’ "U.B.R., the Unauthorized Biography Of Rakim."

Big up, man.

When people don't know the whole story, they try to fill in the holes in themselves, especially if they appreciate the culture or they're a big fan of the work. What are some of the biggest misconceptions about Rakim?

I think the one that used to get me the most was that I was a drug dealer. It got to the point where I started defending myself as if I was a drug dealer. One day I caught myself and I was like, yo man, this is a problem. Just trying to understand like Ra, people going to say what they feel, they assume things, whatever the case is. And I just had to get used to being a part of the world. You open yourself up for so much criticism and just so much opinions, so it took me a while to grasp that concept. I remember once a female came up to me and told me I was conceited and asked did I have a harem. I said is that why you think I'm conceited because you think I got a harem? I never tried to come off like that, but when they say it man, you've got to realize some people see you differently and you have to accept it, regardless of how you feel.

You maintain your image beyond the music. Is it true you turned down roles in gangster movies?

Yeah, they kept trying to give me stereotypical roles, and I was going through that, everybody accusing me of being a drug dealer and now that's all you see me as. They’d tell me to come down and read for a part,“What is it, a drug dealer? No thank you.”

How did it feel when your song “Casualties Of War” was talked about as predicting 9/11? Was that a crazy time?

Yeah, that was a little spooky man. I remember sitting there watching the news when it was taking place. A friend from California called me up, I think I mentioned it in the book, and called me up and he was like "Ra, go on the internet." And this is back in the day AOL, you know what I mean? You get your first page, you've got the news on there, so as soon as I cut it on, I see pictures of the buildings burning and I focus in right next to that and it says "Rakim predicts 9-11." I just feel the hair grow on my bald head.

It's just one of them things where you try to tune in with the present and you try to see the future, being a writer. I don't know if it was that divine, universal conscious or just common sense, but it's a dope record and it is one of them joints that to this day it gives me fuel knowing that I'm on the right path and I'm seeing and speaking on what I feel I should be speaking on.

You are going down as one of the greatest lyricists ever— if not the greatest—but what do you want to be remembered for personally?

I think the number one thing is just that I’m a good person. Hopefully my personality and who I am speaks through my music and people realize that the reason why he made good music was because he was a good dude first and from that came everything else I did. I want to be respected as a man first and an artist second. I'm a father, brother, and I value that. When it comes time for me to sit down and write, if all my values and my thoughts are right, everything else should be good.

Shares