As we begin our march toward the holiday shopping season, November's new book releases are proof that readers will be spoiled for choice this year. Notable essay collections coming this month include new collections from two of our most exciting voices in cultural criticism — Lindy West's "The Witches Are Coming" (catch West in conversation with "Salon Talks" on Tuesday, Nov. 5, the book's release day) and Darryl Pickney's "Busted in New York and Other Essays" (Nov. 12) — as well as comedian Jenny Slate's "Little Weirds" (also out Nov. 5) and Michael Eric Dyson's definitive close reading of Hova's lyrics in "Jay-Z: Made in America" (Nov. 26).

Through in-depth reporting of structural inequality as it affects real people in Detroit, Jodie Adams Kirshner's "Broke: Hardship and Resilience in a City of Broken Promises" examines one side of the economic divide in America, while Kristen Richardson offers an insightful and surprisingly relevant look at the traditions of the affluent in "The Season: A Social History of the Debutante," both out Nov. 19. On the fiction side, keep an eye out for Dave Eggers' new satire of contemporary American politics, "The Captain and the Glory: An Entertainment" (Nov. 19), about an ignorant and inexperienced disruptor whose antics might run a noble ship into the ground. (Sound familiar?)

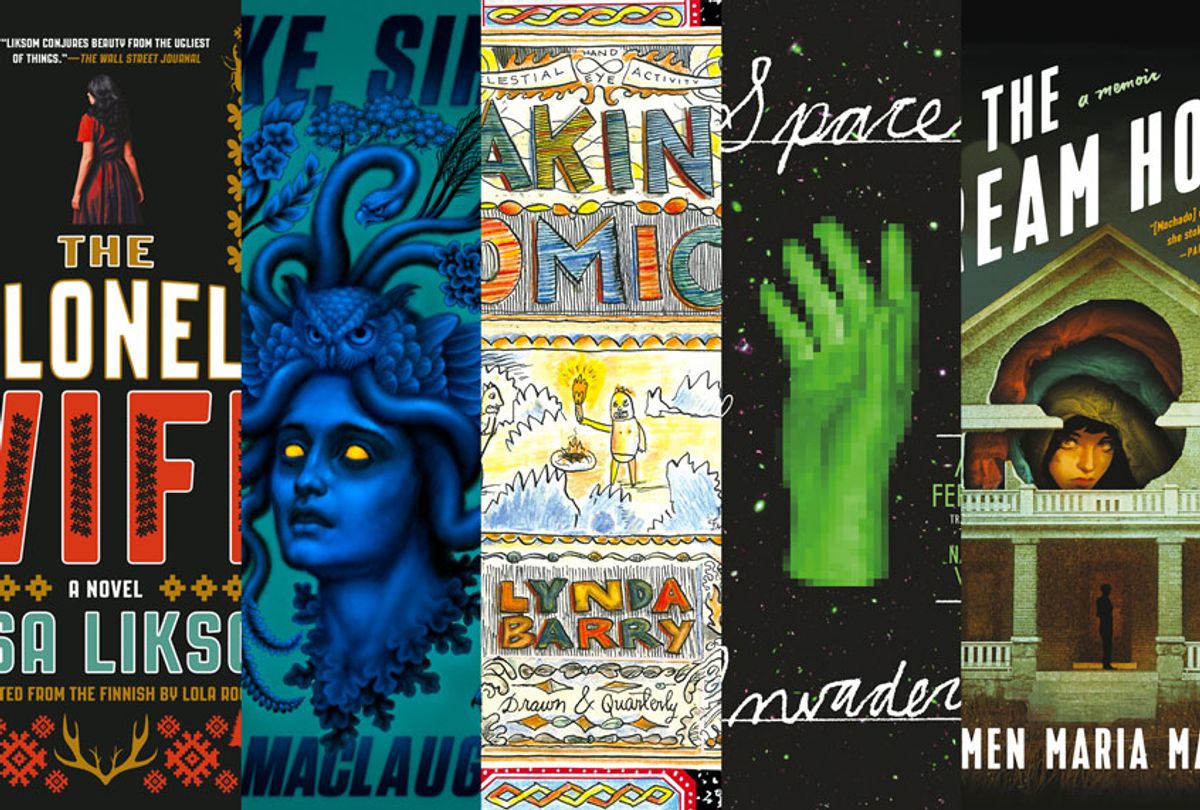

And here are five books selected by Salon staff for a closer look: A groundbreaking memoir, a highly-anticipated guide for aspiring artists, and three compelling novels that demonstrate how stories of the past remain all too relevant today.

“In the Dream House” by Carmen Maria Machado (Nov. 5)

Uncommon is the memoir that explodes our expectations for the genre on several levels. From the inventive hands of Carmen Maria Machado, whose 2017 horror-inspired story collection “Her Body and Other Parties” was a finalist for the National Book Award, “In the Dream House” — a devastating chronicle, interrogation and historical contextualization of her experience in an abusive relationship — is no less than a brilliant revision of the form.

Machado unspools the narrative of her relationship with the unnamed woman, a fellow writer whose intensity and charm transforms into emotional and mental violence, through the lenses of dozens of literary tropes and metaphors in brief chapters titled accordingly: “Dream House as Creature Feature,” “Dream House as River Lethe,” “Dream House as Noir” and “Dream House as Demonic Possession.”

The form resists funneling through a traditional linear plot, and instead insists the relationship — rendered in extended metaphor as the house they selected together and in which the girlfriend lived full-time — be considered as a whole made up of episodes, details, and moments of figurative resonance. (“Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure” is especially effective in illustrating an abuser’s bewildering and terrifying volatility.)

Abuse occurring in the context of a queer relationship is examined in full. In “Dream House as American Gothic,” to cite one example, Machado dismantles the heteronormativity of the gothic romance, demonstrating how its two requirements — “woman plus habitation” and “marrying a stranger” — fit her relationship as well. “We were not married; she was not a dark and brooding man. It was hardly a crumbling ancestral manor; just a single-family home, built at the beginning of the Great Depression.” Nevertheless, all of the elements are present in Machado’s memoir, including the devastating horror that infiltrates then destroys the domestic dream.

“I enter into the archive,” Machado writes in the prologue, “that domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity is both possible and not uncommon, and that it can look something like this.”

That “I” is significant; throughout most of the book, Machado writes to her past self in the second person, the “you” of her address creating both intimacy and distance — between the narrator’s two selves, both present-day and once-upon-a-time, and between reader and narrator. The Dream House, she writes — both an accounting and an invitation — was a haunted house, and “you are this house’s ghost: you are the one wandering from room to room with no purpose." For the reader, though, Machado has written into her map a rich legend to guide us. — Erin Keane

"The Colonel’s Wife" by Rosa Liksom, translated by Lola Rogers (Nov. 5)

Like Nina MacLaughlin's “Wake, Siren” (also reviewed below), “The Colonel’s Wife” is a novel that is all the more thought-provoking and heart-rending in our current strained sociopolitical moment. Written by Rosa Liksom and translated from Finnish by Lola Rogers, this novel is a series of vignettes written from the perspective of a widow who recounts her turn from a wild girl to a young woman who found her sense of belonging in the world of Nazism.

This isn’t a book about regrets or seeking repentance; the titular Colonel's wife is a complex, repulsive and dark character. “There was only one leader for us,” she writes of her family, “And it was Hitler.” In reading this novel, I had real difficulty at times separating my interest in the book and the rage I felt towards the narrator for her abhorrent views, especially as she was written without a desire for any level of introspection at the end of her life.

But the language Liksom uses has a kind of grave, paradoxical beauty which fortifies the narrator’s memories, especially when writing about the Colonel, who was 30 years older than his wife. The two shared a tumultuous relationship — that was, at various times, dictated by burning sexual attraction, horrendous abuse and a fervent dedication to the burgeoning Nazi elite.

In total, “The Colonel’s Wife” is equal parts horrifying and fascinating, with only a few moments that noticeably drag. — Ashlie D. Stevens

“Making Comics” by Lynda Barry (Nov. 5)

If you’re not a student at one of the two universities where MacArthur Fellow (read: certified genius) Lynda Barry teaches cartooning, but you want to learn from her inspiring and accessible techniques, you’re in luck. “Making Comics,” the follow-up to her 2014 bestselling “Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor,” is out this month from Drawn & Quarterly.

“I knew I couldn’t teach the kind of cartooning that people call ‘professional’ but I wondered if I could teach what I knew about the power of comics as a way of seeing and being in the world and transmitting our experience of it,” Barry writes in this beautifully bound illustrated volume of classroom notes, how-tos, practical lessons, pedagogical rationales, and abundant examples from her students and her own pen.

“Making Comics” takes the form of a hand-lettered and –drawn composition notebook, the type Barry assigns her students to use in her actual class. Barry pairs a spirit of wise and open encouragement — that we already know how to draw since we were doing that before we could write, we’ve just forgotten or convinced ourselves otherwise — with a demand for rigor, especially in creating a physically and mentally present, analog environment.

Barry’s delightful style may be inimitable, but the underlying thesis of “Making Comics” is that anyone can discover their own cartooning genius, if they are willing to put in the work. Give yourself the gift of time and quiet. Draw yourself as Batman in three minutes without stopping. Let your hand respond to the question, “And then what happened?” Repeat until all frames are done. Show up on time, and do it again. — E.K.

“Space Invaders” by Nona Fernández, translated by Natasha Wimmer (Nov. 5)

This slender, elegiac novel by acclaimed Chilean author Nona Fernández follows a group of school kids in Santiago growing up in the shadow of the brutal Augusto Pinochet regime. In adulthood, their memories — or are they dreams? — revolve around one of their classmates, Estrella González, whose father they come to learn is a high-ranking officer in the dictator's state police.

Estrella leaves school after a vicious episode of violent retribution against suspected members of the resistance, her absence a wound that refuses to heal. As the memories of childhood march forward, the other children experience a gradual awakening to their horrific political realities — kidnappings, disappearances, executions, torture — set against the backdrop of the mundane discoveries of adolescence, from make-out parties to playing video games like "Space Invaders" for hours on end, destroying the seemingly never-ending supply of destruction hurtled at them as fast as they can in order to halt its advancement. The glowing green alien invaders of the game, unlike the funerals that begin to overwhelm their waking lives, can be stopped.

Years after they are separated, Estrella and all that she represents still haunts each of them in the singular vocabulary of their memories: one dreams of words written in blue ball-point pen like the letters they exchanged as girls; another of hands, an echo of the prosthetic he saw Estrella's terrifying father unbuttoning and removing in their home.

And who's to say what was even real to begin with? "We don't know whether this is a dream or a memory," the narrator says of the moment when they crossed irrevocably into the adult territory of politics and dissidence before they even knew what that would mean. "It might have been staged or even made-up, but the more we think about it the more we're sure it's just a dream that gradually became memory." In short poetic chapters in which layers of meaning and emotion are compressed into each sentence, Fernández illustrates one more devastating way autocracy robs people, when it steals their ability to ever know for sure what reality is, or was. — EK

"Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung" by Nina MacLaughlin — Nov. 19 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

So many other people have tried to tell my story. For a long time it made me disbelieve what I knew was true. Now, I tell it myself, with the force of the words that I choose. These are words spoken by Medusa, the monstress with hair of writhing serpents whose gaze turned men to stone. In Greek mythology, she is beheaded by Perseus who kept her head to use as a weapon; in Nina MacLaughlin’s “Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung” she is exiled and angry. There have been enough retellings of her story to create a tidal wave, but none of which got the facts right. None of which talked about how Neptune had raped her (most instead using some variation of the term “deflowered”). None of which talked about how Minerva watched and said nothing — then punished Medusa for Neptune’s actions.

It’s not the snakes that are so petrifying to people. It’s not the serpents writhing from my head that turn people to stone. Don’t you know? It is my rage.

It’s lines like this that make it all too clear that though the stories collected in “Wake, Siren” have their roots in the myths of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” which was originally published around 8 A.D., this reimagining is all too timely, needed and cathartic. In each retelling of stories we thought we knew — from Arachne, the weaving woman who challenged the gods and was turned into a spider, to Io, the mortal who was turned into a cow — MacLaughlin simultaneously asks and answers a question: “What do we lose when the stories of women are told, translated and retold by men?”

Through language that, like the sea nymph Thetis, shape-shifts between poetry, lyricism, email transcripts, theater and prose, “Wake, Siren” reveals the violence, the pain and the triumph in age-old tales made poignantly new. — ADS

Shares