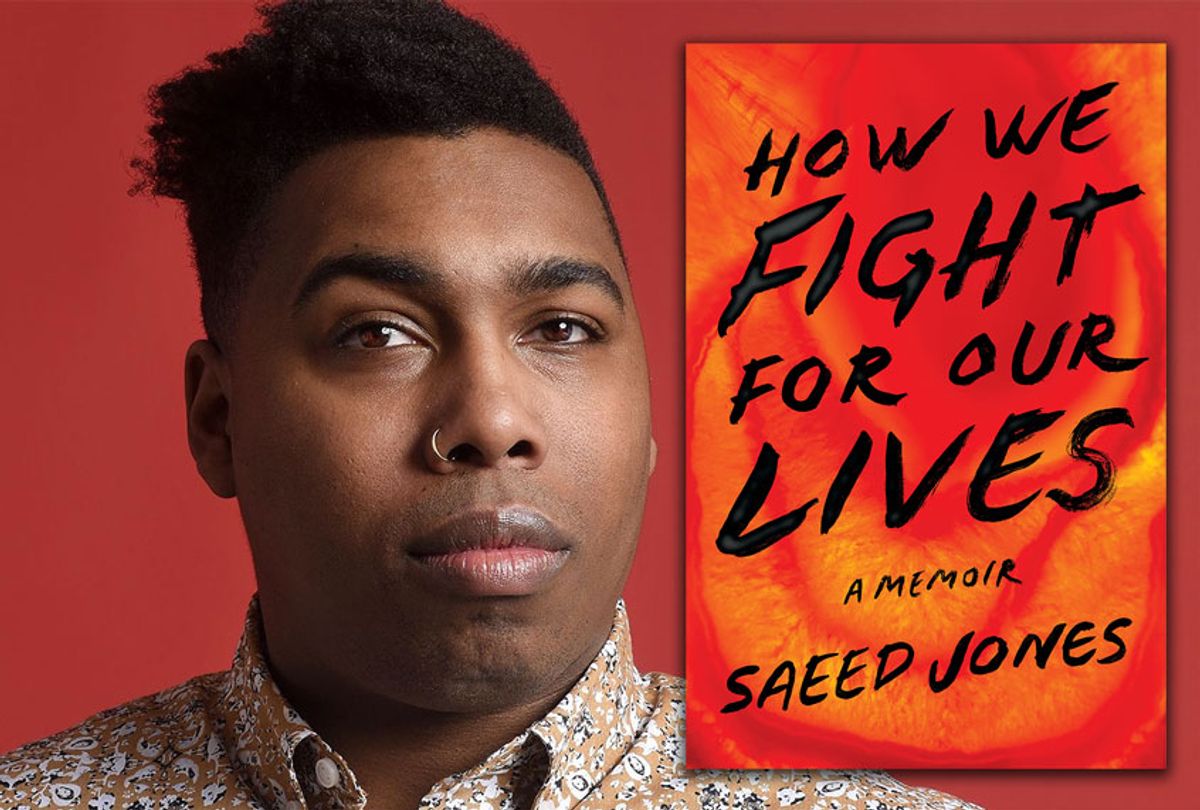

We are truly living in a special time. I sometimes lose track of the many positive changes happening around me: progressive art is being made, black and brown representation in television and film is growing every day, black writers are finally being published widely, studied and celebrated. Diverse voices are being heard. One of the voices leading the charge is Saeed Jones, author of “How We Fight for Our Lives.”

"How We Fight for Our Lives" is a compelling memoir about growing up black and queer in America, a country with a history of not being kind to people who are either or both. In his book, which Jones takes a deep dive into our flawed society and explores how our culture struggles with accepting anything perceived as not normal, and chronicles how he carved his own path through the middle of the endless madness. We learn about his journey through religion, sexuality, queerness and how these complexities are defined and understood in an American black family.

In its starred Kirkus review, the book is praised as "mark[ing] the emergence of a major literary voice.” Jacqueline Woodson, National Book Award-winning author of “Brooklyn,” wrote the book is “Everything everyone needs right now — both love song and battle cry, brilliant as f••k and, at times, heartbreaking as hell. Every single living half-grown and grown-up body needs to read this book. I’m shook. I’m changed.”

The praise around "How We Fight for Our Lives,” is well-deserved, and the fact that it is a standout title this year points to how much progress has been made in our lifetime. Like me, Jones was born in the early '80s, when there weren’t many books available that explored experiences like his. And if he did come across a book that celebrated blackness, the protagonists weren’t likely to be LGBTQ as well.

As a kid, Jones would dig through piles of his mom’s books looking for inspiration, coming up short every time until he accidentally came across James Baldwin's novel “Another Country.” It was so good the young Jones thought he would get in trouble for reading it. That book changed his life; it taught him that reading isn’t a chore — that it can be fun, even radical. Baldwin taught Jones that reading is a blessing. And because of that blessing, we are now able to read Jones’ work and gain a better understanding of his story. Young men who have had the same struggles as he has now have a contemporary book that celebrates an authentic American black queer experience.

"How We Fight for Our Lives" won the 2019 Kirkus Prize for nonfiction, which comes with a $50,000 award. I caught up with Jones recently by phone to discuss reading, life on the road, representation, his wonderful book and what’s next.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

You have a background in writing poetry. Was switching to memoir difficult?

It’s a very specific experience, because it’s not just a book, it’s an encapsulation of a part of my life. It’s about my family and mom. I'm happy it worked out, but everything means a little bit more — it’s not just content, it’s a personal history of loved ones, and more vulnerable than the poetry I published.

Vulnerable it is. But I still appreciate the craft. We both know in memoir, [readers] aren’t just judging craft, they're judging you.

I agree. People aren’t just engaging the writing. I hope they are engaging with the writing, as I worked really hard on the craft of the book, but there is also the fact of my life. The fact of my past and the story itself, people are also engaging in, and that’s just more — you got more skin in the game.

The book is being received really well. Was that expected?

I try not to have expectations because you just never know. I like to focus on my intention, which was to accurately evoke what I learned about myself during that coming-of-age period in my life. And by the time I finished the book, I felt confident that I done that. And anything else that has happened has been wonderful but secondary to the original goal.

I keep going back to the idea of what kinds of books were available to young black men like us, who were born in the '80s and raised in the '90s. I didn’t have books at home, but you had your moms’ books, like "The Color Purple" and Baldwin’s "Another Country." They were great reads, but not contemporary, and couldn’t speak to the blackness and experience of a young gay man like you. Now your book is here, and it is going to do that for so many people. They are going to read you and know that they're not alone.

That’s such an exciting feeling.

You will essentially be their big homie. How do you feel about that?

[Laughs.] That is wonderful. In some ways, that is the work I’m always trying to do. Young, queer black people are always first and foremost on my mind. I think it’s important for us to continue that work, be empowered and tell our own stories, because readers need a diverse range of work. I can’t speak to everyone, I can only speak to what I know and what resonates with me. I feel honored to be given the opportunity to put another book on that figurative book shelf. We still need so much more.

Good things are happening; it’s hard to celebrate while knowing so much pain still exists.

It feels good to see some of our icons like Billy Porter being celebrated, and his peers, to see black trans women get recognized for not just who they are, but their talents and brilliance, like Janet Mock signing that Netflix deal. It does feel like a lot of steps are being taken. But we have so much work to do — trans women are being killed at an alarming rate and we need to fight, which means more than just social media activism.

Does your writing deliver a type of humanity you didn’t get growing up? Do you even think about that or do you just think about telling the story?

I think often that if I do my job as the storyteller, it’s going to resonate with unexpected readers. When I follow through with my intentions, then I hope a natural growth out of that effort will connect with people. Like when I brought my mother to life on the page and really colored the emotional nuances of our relationship, then you do not need to be me to understand why she was a special person, why we had a special relationship. And certainly, to understand the depths of the struggle for two people who love each other so very much. I don’t go out of my way to be an ambassador to straight people or to white people, but if I do my job well it’s going to happen.

Right — I’m too busy being oppressed to explain to another person what that means or how they should be treating me.

Absolutely.

You do a great job with condensing these big ideas as well. I can’t believe this book holds so much weight and yet it’s 190 pages. Was that difficult?

As a poet, I have a natural affinity for economy of language so it wasn’t rough. And I personally don’t really like long books. I’m a voracious reader and I’m curious about the world so to be invested in one book, one film or one piece of art, then you are also not doing other things.

And when people are engaging my work, I don’t want them to feel like I’m wasting their time. I want everything they feel when reading my work to be significant, of use and illustrative, so it was important for me to keep the story tight to honor that. Your time is really valuable, so let me get to it.

I was walking around downtown Seattle 20 minutes ago and a young woman saw me and her eyes lit up. She said, “Saeed, I follow you online. I read the book and I finished it in five hours!” I think there's something special about having a book that is a tight jewel. It becomes something that people can experience and then pass on and get a great conversation going.

You write so much about your home town of Lewisville, Texas, in the book. Have you been back on book tour?

I did an event in North Dallas, which was pretty close, and some of my high school teachers, speech and debate coaches, former classmates and a lot of family members showed up. I have a lot of family in both Memphis and the Dallas area.

Did anybody take issue with the way they were portrayed in the book? Angry family, left-out friends?

No, I shared the book with my grandma Mildred, my Uncle Albert and my mom’s sister before it came out and it surprisingly led to some good conversations that my family never really talked about. My grandma said that the beginning of the book was difficult and it brought back a lot of memories, and [she] didn’t try to reframe or make excuses. She just listened. We have a complicated relationship, and that’s human, so I tried to show all of the facets of that relationship — the good and the bad and the in-between — and she trusted me. My grandma was a complicated character in the book and I am glad I got to honor her and that complication.

Nobody is just one thing. Telling the whole story is what I love about memoir the most. What’s next for you?

I’m writing poems now, but the tour has been a lot and quiet time is next for me. I’m grateful for all of the readers of this book and the attention, the accolades the book has garnered, which is wonderful but it’s also very loud. Many don’t know but I’m actually a pretty quiet person and I need that quiet to think so that I can make decisions. I don’t know what I’m doing next as of now, but I know it will be something different from "How We Fight for Our Lives." That I can promise.

Shares