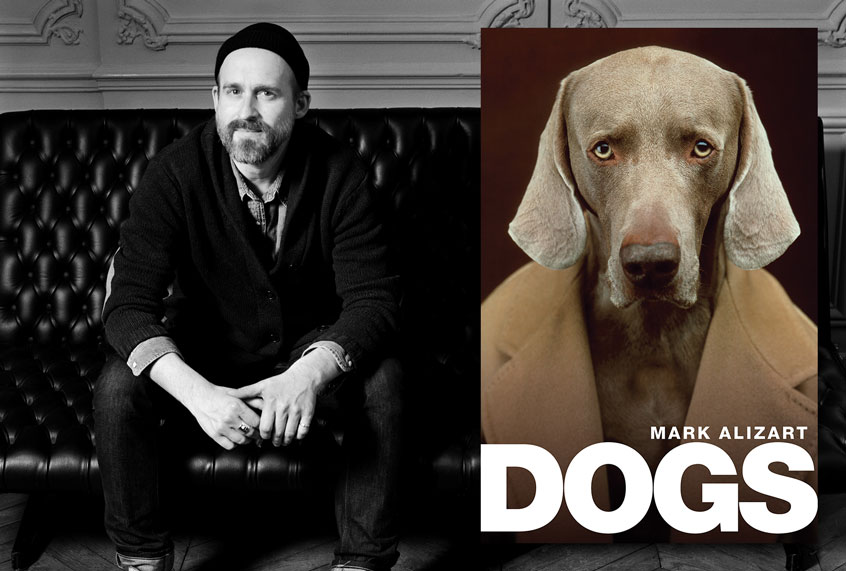

Have we tamed dogs, or did dogs choose to be submissive to us? Are they actually submissive, or are they master tacticians, wiser than humans could ever comprehend? These are philosophical questions philosopher Mark Alizart wrestles with in his new book, “Dogs: A Philosophical Guide to Our Best Friends.”

Surely, all dog owners have stared into their dogs’ eyes and wondered what they were thinking, but what is as equally mysterious as how humans have evolved with these animals. Dogs and humans have traveled and lived together for thousands of years, and clearly, provide mutual evolutionary benefit: dogs helped prehistoric humans hunt, and we in turn fed them and kept their company. Indeed, it is worth asking if humans would be here today — at least in our current form — without the help of dogs.

Nowadays, dogs are less likely to be working dogs and more likely to be members of our family, whose primary utility is their companionship. We spend billions every year on them, and spoil them with treats, professional haircuts and spa sessions. Perhaps we anthropomorphize dogs, but it is hard not to do so given how they seem to be so connected to humans.

When Alizart’s dog died, he sought comfort in literature, but couldn’t find a meaningful book that thoughtfully explored the human-dog relationship. This led him to writing his own. I interviewed him about his new book and how a philosopher thinks about dogs; as usual, this interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I just finished your book. I loved it.

Oh, thank you!

I’m a dog owner, so you know.

You’re a dog person.

I’m a dog person, thinking about dogs all the time. I would love to hear more about what inspired you to write this book, especially from the perspective of a philosopher.

Well, to be very honest, I had no plan [to] write this book, especially because I’m a philosopher and I didn’t expect that dogs would come up in my thinking and my work. What really got me to write it is because I was forced to — because I owned a dog, and then he had the terrible idea of dying very young. It was my first dog, and I was afflicted by his passing. It took me one year of mourning until I realized I needed to do something about it. The only thing I could think about was to write about him, maybe write him some kind of letter or something.

I couldn’t find any relief in books or films, the kind of things you would turn to when you lose a dog. The books that are about dogs are only for children, or for animal handlers. I couldn’t find very noble, majestic grand figures of dogs that could remind me of the relationship I had with my dog. There was nothing close to what I had lived with my dog, and I thought something really needed to be done about this.

So that that’s when it really became philosophical, in a sense. I mean, every country has an animal as an emblem. Traditionally, the United States is the bald eagle. Or you know, England, the lion. Absolutely no country has a dog for an emblem. How is that possible that we love dogs so much, and they’ve been around for so long, and still we don’t find any dogs anywhere to represent us? So that’s the kind of philosophical question that’s behind the book, and that has made the book become something that really entered my philosophical world.

I’m so sorry about your dog.

It’s an experience every dog-owner goes through. I’m pretty sure that the whole experience of having this dog, of having him and losing him, made a better person out of me.

This book holds so much meaning for dogs, and you make the argument that dogs are like gods or angels, and I just kind of imagine that we should be living in a world where we make altars for our dogs, and pray to them. And I’m curious where you think our relationship — the human relationship with dogs — is headed now?

Well, the reason why dogs were worshiped, and considered kind of demigods in antiquity, or even why they could be said to be angels, is because they are really fascinating creatures. In the sense that they are the only creatures we know of, maybe, which are one part of them in nature, and another part in culture. They’re a bridge between nature and culture, between the world of the animal kingdom, and the human kingdom and civilization. So in a sense they’re ambassadors of nature coming towards us, and this is why you see dogs associated with the gods of death, which are really the gods of passage, of thresholds. Dogs bring people from life to death, and help them navigate towards the infernos in Greek mythology, or Egyptian mythology.

And strangely enough, I think we’re getting back to that kind of relationship with dogs, especially probably because our relationship with nature is now so crucial, that we have to find it again, to find a way, a passage towards nature again. I think we’re rediscovering this ancient relationship that dogs enable us to have with the otherness of nature. We need to be reassured that we still have a relationship with nature, and that we are able to live in harmony with nature. And dogs are the ones who really tell us about this, that it is possible, and that it is needed.

I think the book just does such a great job of weaving together the complex roles that dogs have held in history, mythology, and religion. And today I think that dogs seem to be held, obviously, in a really high regard, especially in first-world countries. But there are also some ways in which they’re held at a sort of a lower regard. And I think that comes out, and as you mentioned in your book, in our language and in some derogatory phrases, and I’m wondering if you think we should be showing dogs more respect by moving those negative phrases like, “You eat like a dog,” or “You sleep like a dog,” or even the word “bitch,” in English.

Well obviously, yes, I think that. I think dogs deserve better, and I think every dog owner actually ceases very quickly to use these words, as you know. But they have a very long history. They have a deep history. And they also say something about another deeper meaning of dogs, which is linked to, to our unconscious, to repressed emotions, to sexuality. That’s what it’s about, really. Dogs are very peculiar, because as I was saying, they’re these in-between world animals, and they’re also in-between concepts. We have this fairly stereotyped way of seeing the world that we’ve inherited from many centuries of masculinity and patriarchy, which are the idea that masculine is good, that masculine is the dominant activity, freedom, wilderness, and we tend to unconsciously relate to the world like that.

There’s all these positive values on the one side, and all the rest, by definition, has to be negative. That which means passivity, tamed femininity, and this is so pervasive, it’s sunk into our culture so much, it’s very difficult to get rid of. Dogs actually play a very weird role in this, because they’re on both sides, yet again. They can be very muscular, very aggressive, and some people like to show off very muscular dogs as a sign of manhood. And on the other side, on the other hand, dogs are obviously tamed animals, which means that they’re on the other side of the divide. They’re home animals. They even seem to enjoy their passivity, or the obvious fact that they have a master, which is so weird for us to understand, because we have this stupid, rigid, way of imagining that submission is bad. Or that they haven’t been submissive, or that we have tamed them, and we have kind of stolen their freedom. And that is so wrong. That is so, so stupid. But, it’s engraved in our culture. People who’ve worked on the way we have co-evolved with dogs are able to understand that dogs actually have not been tamed, but that we have built an equal relationship with them.

That’s interesting, you say that it’s like an equal relationship. I like thinking about that. I think that they in a way they choose us as well.

People have an experience of being submissive to something without feeling they have given up, and that is their own kids. I mean your kids are your masters, in a sense. When you have kids, that’s it. You experience this submissiveness, but it’s not a bad feeling. It’s actually a liberation, or something, It’s enjoyable, and it’s more complicated than people tend to think, this relationship. It’s not a one-way relationship.

We have to understand also that dogs are not our children, and that we can change our relationship to them if we understand. If we make the effort of imagining that they’re our parents, it’s ‘s a very weird experience to do, but not calling our dogs, “my baby,” but calling them, “grandpa,” or “grandma,” or whatever, can be very interesting in changing our points of views on what dogs are. It’s not that crazy to do because dogs have been around for longer than us, and in a sense we descend of dogs as much as we descend of apes. Without dogs, human beings would not have been able to civilize, as they did.

As you mentioned, humans wouldn’t have been able to evolve the way we have without dogs, and perhaps even survive. And I think it’s made me think about how we are obviously headed toward another kind of human crisis: climate change. And I’m wondering if you think dogs will play a role in human survival, and the challenges we’re expected to face in the future too.

My understanding is that we might have to become more like dogs in order to survive all this turmoil, and to change the world. Meaning, we have to free ourselves from what we were talking about earlier on, which is all these stupid hierarchies, and this construction of masculinity, and toxic masculinity, which dogs break up. That’s what we have to liberate ourselves from. And dogs can help us to do that. And in that way I would say, yes, we ask of you to become more like dogs. To be as gentle, delicate and understanding as dogs.

And, what makes me think about that, as well, is how many saints in medieval times likened themselves to dogs, because they saw in dogs these qualities, these ethical qualities, that I’ve been talking about. They believe that dogs have this simplicity, the modesty of what a true Christian should be. The most famous one being Saint Dominic. Saint Dominic owes his name to, well, a dream his mother made, where she dreamed that she was giving birth to a dog holding the torch of truth in his mouth.

That would probably be the last thing you wanted to be, is to be a dog. Because as you were saying, it’s considered as an insult. I mean who would want to be a dog? But actually I think dogs’ lives are full of teachings for us.

How else can we be like dogs?

There’s also this question of nonviolence we could add to this, you know?

Right, totally.

We’ve learned from Martin Luther King Jr., or Gandhi, that nonviolence is a fundamental drive and power in the world. And I don’t mean to say dogs are nonviolent, because dogs can be violent, and I don’t want to idolize dogs either. But I do have this feeling that the power of dogs, is the power of nonviolence. And that’s another thing we can learn. Dogs are also always open to what comes their way, and that’s part of the fantastic delight of being with them. But there is something about this spirit of not disrupting the world — which is quite amazing, because dogs are scavengers, they don’t hunt. They don’t hunt living animals unless you teach them.

Could you share more about what dogs have taught you about joy?

Well, first of all, there’s this weird thing about the joy of dogs, because as we were saying, a dog’s life is maybe not the best of lives. And we would probably think that dogs should not be happy about anything. I mean, dogs are not the only happy animals around; elephants have joy, and dolphins, and apes, and even parrots. But dogs are so specific, because as I was saying, they’re scavengers. We can imagine that they would be like hyenas, or vultures, that they would be scary and a bit dark. And also, they could be depressed, like zoo animals, and they’re not.

They’re not, because they seem to have found a way to keep up that point of view on existence, which is very singular. So, some people say it’s just that we’ve bred them that way. We just choose the least aggressive animals. I think it’s something different. I think it’s like a drive to life. It’s like dogs seem to be possessed by the will to be.

If you just take an example: my dog is the most happy when we manage to communicate to create a canal of transmission between us. When he understands what I want from him, or when he manages to make himself understood by me. I can see in his eyes if something is triggered, if something is opening, and that’s fascinating. That’s why I called it a “drive to be.” It’s a flow of energy coming from nature that wants to explode.

We are happy when we create things. When we create things which are bigger than us, like dogs have been happy to create us in a sense, to further evolution, to further this desire of nature, to know itself, and to grow.

I think it just means that we’re not the owners of nature, or life, or the universe, but all these things go through us, and we need to continue the story. I think that’s what dogs, really, fundamentally, philosophically, have to tell us about the world.