The morning after the recent American raid on the compound of elusive ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, U.S. President Donald Trump put his penchant for media spectacle on triumphant display.

He delivered a dramatic 48-minute news conference during which he embellished or fabricated the description of the raid and even revealed some classified information.

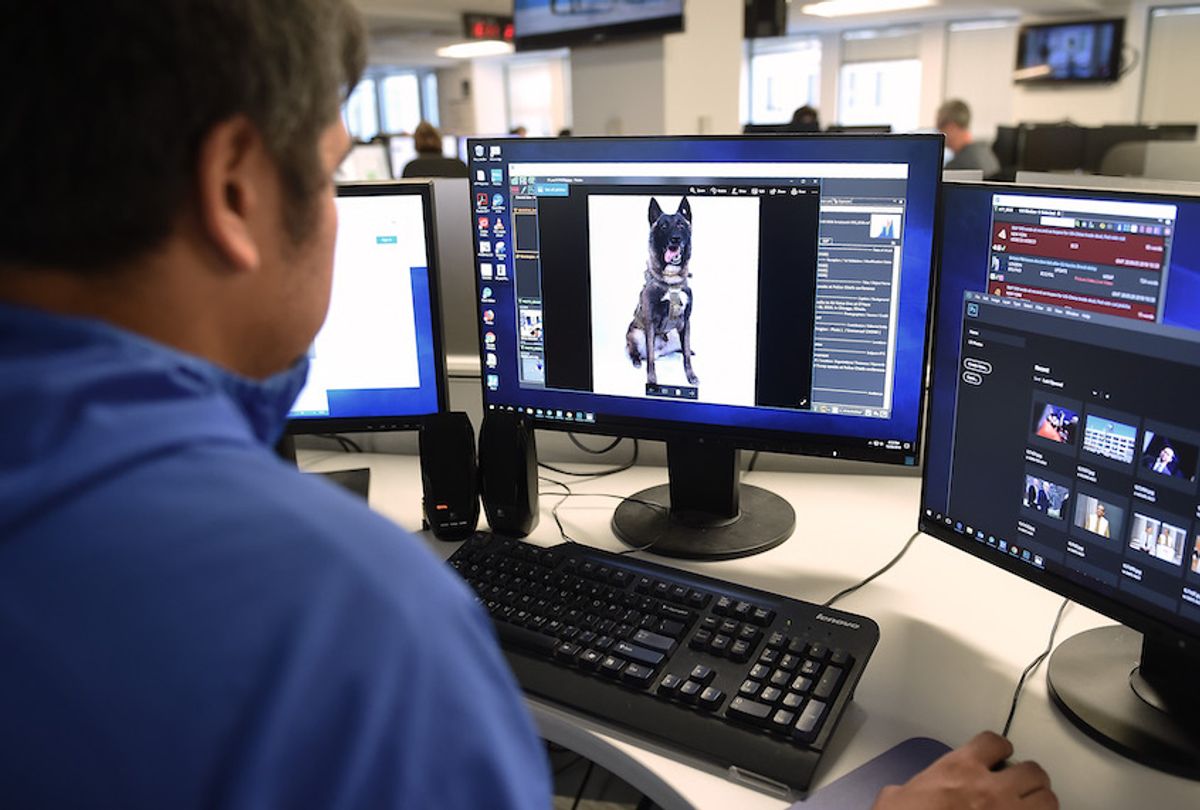

At several points, Trump called attention to the military working dog that took part in the raid and was slightly injured, and employed an abundance of canine imagery to refer to ISIS and al-Baghdadi.

He lavished praise on the “beautiful” and “talented” dog that chased al-Baghdadi into a tunnel where he detonated his own suicide vest, killing himself and some children. In contrast, Trump labelled ISIS followers “sick puppies” and al-Baghdadi “a sick and depraved man,” “a coward” who, “whimpering, screaming and crying” “died like a dog.”

Al-Baghdadi’s responsibility for widespread torture, rape and murder is undisputed. The raid was named in honour of the late Kayla Mueller, an American aid worker who was raped by al-Baghdadi.

However, since the news conference, it’s been the dog — a Belgian malinois identified as Conan — that has taken centre stage, not Mueller, Trump, al-Baghdadi or ISIS.

The Pentagon, acknowledging the high level of interest in Conan and its K-9 program, stated that military working dogs are “critical members of our forces” and perform several roles, among them protecting soldiers, separating combatants from non-combatants and saving civilian lives.

Dogs often used in wartime

Indeed, specially trained dogs have long been engaged in wartime, policing and crowd control and, since 9-11, in the “war on terror.”

In fact, Cairo, another Belgian malinois, was part of the 2011 U.S. Navy SEAL operation that led to the assassination of al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden when Barack Obama was president.

The death of such dogs is generally seen as a tragedy; when Diesel, a Belgian malinois involved in a 2015 raid on a suspected ISIS terrorist hideout in Paris was killed, many proclaimed “Je suis chien” and “Je suis Diesel” in tribute.

The public fascination with these dogs highlights the peculiar place occupied by the species Canis lupus familiaris in the western world. Sought after for their domestic companionship and superior sense of smell and hearing, dogs are also valued for the savagery they can unleash on command.

Racialized people targeted

Cuban bloodhounds were used in the Americas in the service of colonization. In the American South, bloodhounds working with slave hunters tracked the scent of African-American fugitive slaves, often injuring them upon capture. Slaves escaping bondage reported being more afraid of the dogs than the wild animals they encountered.

During the Civil Rights movement, police dogs confronted Martin Luther King Jr.’s Children’s Crusade. Media coverage of white male police officers leading German shepherds that lunged at young African-American students drew negative publicity to Birmingham, Ala. The city’s memorial to the crusade depicts just this scenario.

Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib trophy photos showed American soldiers subjecting Iraqi and Afghan prisoners to horrific tortures, including snarling German shepherds threatening both clothed and naked prisoners.

In some instances, senior military staff encouraged soldiers to treat prisoners like dogs; some, including a white female soldier, forced prisoners to wear dog collars and leashes.

Statistics demonstrating that police dogs are more likely to be found patrolling African-American and Latino neighbourhoods in Los Angeles provide more evidence that military and police working dogs have been co-opted into dehumanizing racialized populations.

"Alpha dog"

In effect, specially trained dogs perform by proxy the dominance attributed to the slave owners of the past and today’s mostly white military and police and, regardless of the gender of the dogs or their handlers, hegemonic masculinity.

Trump’s use of canine imagery against the ISIS leader and his followers establishes the president’s alpha dog status over subordinates, and their submission to him.

Indeed, Trump, the first president in a century not to keep a pet dog at the White House, has long used the word “dog” to deride and humiliate enemies, critics and women in particular.

Flesh-and-blood Conan appears to have elicited warmer feelings. Trump, who shirked service in the Vietnam War, faces an impeachment inquiry and is eager to best Obama’s achievements, understandably wishes to capitalize on the dog’s “American hero” status.

He tweeted an image of himself awarding a medal to a real-life Vietnam veteran who was photo-shopped to look like Conan and has even invited the dog to visit the White House.

Trump’s newfound and likely transactional affection for a high-performing dog should not distract a nation from his administration’s disgraceful dealings with migrants, refugees and minorities.

And the rapturous stories of the heroism and sacrifice of specially trained military and police dogs, however moving, should not obfuscate the history of their ugly deployment against racialized peoples, and their current use doing the same work.

Christabelle Sethna, Professor, Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies, University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares