The car was coasting. Kai heard the wheels crunch as it drew to a halt outside his house. The car door opened, and a young man hopped out. He popped the hood and disappeared beneath it. “You’ve got to be kidding me!” he fumed.

Kai emerged from the front yard. It was late in the morning, and the street was empty. Cars were a rare sight around there. Kai often played in the street with his sisters. Mostly only bikes passed by, anyway—students on their way to class. Kai lived with his parents and sisters on a sprawling college campus, which boasted sculptures, water fountains, benches, flame trees, a Japanese garden, and enough space to spend the whole day wandering idly, accompanied by chirping birds.

“Hello. I’m Kai.”

The man ignored him.

“Is your car not working?”

“No,” the man grumbled. How would he get to class now? He was stuck in this damn residential area and would be too late for his exam. If he didn’t make it there on time, they’d mark him absent and fail him.

Kai spun around and dashed off. The man got back in his car and turned the key. The engine sputtered for a moment and died again.

The boy came running back. What the hell did he want? He was holding something in his hand.

“Here,” said Kai. “My mom’s key.”

“Excuse me?”

“You can take our car.”

* * *

Kai loved people, and it was hard not to love him back. At the age of two, he started twisting his way out of his father’s grip and running over to them—random pedestrians, the postman, elderly people sitting on benches basking in the warmth of the morning sun. Kai opened his arms and clung to their legs. He didn’t say anything. They froze at first, but when they looked down to see his twinkling brown eyes staring up at them, they couldn’t help but laugh. Kai didn’t speak much. He spoke with his hands and glowed from inside. He warmed their hearts more than the sun possibly could. Soon they were sitting on the benches because of him, the little boy who had just moved to Rehovot, Israel.

Kai was born in Heidelberg, Germany, on June 21, 1994, the first day of summer. It was the longest day of the year and proved to be the longest birth his mother Anat would have to endure, dragging on some twenty hours. While she twisted and turned in pain, Henry wandered up and down the hallway. Their two daughters, Kali and Linoy, would soon have a baby brother. They could barely contain their excitement.

Babies are often born with a smile on their face. Experts call this a reflex smile. It’s a newborn’s way of ingratiating itself. That smile is many parents’ first memory of their child. Henry doesn’t remember if Kai was smiling. He remembers something else: newborn Kai kept trying to lift his little head. His wide eyes had this absorbing glimmer, tracking every light and sound, darting back and forth on high alert.

Henry had treated many babies during his time at medical school, but he had never seen eyes like that. His son’s gaze seemed targeted, intentional. That was impossible. A newborn’s vision doesn’t develop for another few months. Until then, everything is blurry to their eyes—colors, contours. They can only see what’s right in front of them: their parents’ faces, the mother’s breast. Kai, however, behaved as though he could see.

His pupils darted nonstop. Henry was worried. The doctors on the ward huddled. They had never seen a child like that either. As they inspected Kai carefully, the worries vanished from their faces. Kai scored a full ten points on the Apgar test, which rates a newborn by appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration. “All good,” his colleagues told him. Henry’s fears turned to pride: “He is the most alert child on the ward,” he told Anat. “Our son is something special.”

* * *

Kai is different. Kai, the doctors would eventually realize, is autistic. Of course, like everyone on the spectrum, Kai isn’t just autistic—he’s so much more than that. Kai is Kai.

Doctors used to find one case of autism among every five thousand people. Today, according to a study by the US Department of Health & Human Services, the ratio is one in fifty-nine. Scientists speak of an epidemic. Kai may be different, but he is not alone.

Henry is one of the world’s most famous neuroscientists, but when Kai began withdrawing, he was as helpless as all the other parents of autistic children. He asked himself the same questions they did: What is autism? How can I help my child?

He researched for fifteen years. His findings would upend everything we thought we knew about autism, and offer us a new way of thinking about a number of conditions.

If Henry had just been a scientist, even a great one, he would have failed. He only succeeded thanks to Kai, the boy who changed everything.

* * *

It’s 4:00 a.m. Henry throws off the bedcovers. He tiptoes out of the bedroom, across the hallway into the kitchen and makes coffee. Quietly. Everyone is sleeping. He opens his laptop. The bluish light of the screen shines on his face. His eyes are smaller than usual, his hair messy. He is thin. Only a few weeks ago, he was in Portugal on a fasting retreat. He slurps his coffee and reads e-mails.

“Dear Henry,” a lady called Sandra writes to him. “I am autistic. Reading your story, I was overcome by emotion. For the first time in my life, someone was describing my experience. My family doesn’t support me.”

“Dear Sandra,” Henry types. “I know what you’re going through.”

He reads more e-mails from autistic people, their families, his colleagues. He reviews the data—rows of numbers that only a scientist can understand. Finally, he opens a lecture he was working on until midnight. “We think we see with our eyes,” it says, channeling Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. Unlike the Little Prince, however, Henry doesn’t believe we see with our hearts: our brains shape our view of the world.

“The pathways in your brain are so extensive, you could stretch them once around the whole moon: a hundred billion brain cells, a hundred billion synapses, a wonderful system, and six hundred ways to disturb it. Autism, ADHD, depression, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, schizophrenia. How are they all related?”

This question drives Henry out of bed every morning at 4:00 a.m. He is certain it will be answered in our lifetime. Humanity will decode the brain.

* * *

Autism manifests in various ways. If you know an autistic person, you know one and not all of them. Each person is different. Some require foster care. Others are superstars of music or math but are incapable of going shopping by themselves. Some live independent lives and resist being labeled sick or disturbed. To them, autism is a characteristic, a feature, like dyslexia or being left-handed.

At the time when Henry started his research, the experts couldn’t agree on much about autism—so many causes, so many symptoms, hardly any disorder is as multifaceted. But they could all agree that autistic people are not social creature. That they are mind-blinded, could not empathize, that they aren’t even particularly interested in other people. They lack empathy, the experts said. This became an article of faith. And this perpetuated an attitude dating back to the discovery of autism, which viewed people affected by it as essentially flawed. The conventional wisdom was set.

This was more significant and tragic than it may sound. The scientific consensus, which saw autism as a deficit requiring correction, has had a profound influence on how the condition has been researched and medicated. Almost every study was built on the same assumption. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of psychiatrists and psychologists, which defines and classifies diseases, placed autism in a class of mental disabilities. This guided all further research. Some studies searched for the causes of the deficit. Others tried to remedy it. Hardly anyone considered that perhaps there was no deficit at all.

Also Henry was searching for this deficit. But there was Kai. He brought something to his research that is often lacking in scientific inquiry: the constant confrontation with reality. And Kai didn’t behave as an autistic person was supposed to. He contradicted the studies, the doctrine. For years, Henry tried to reconcile Kai’s behavior with the old consensus; but then he dared to do something they never would have dared to do if it hadn’t been for him: he questioned the old dogma. Kai and him, together, they were a force. They were strong enough to go where no one in autism research had gone before: the fusion of life and learning.

* * *

After months of research Tania, Henry’s assistant professor, stood there, alone in her lab. She stabbed the micropipette into the patch, stimulated it, and could hardly believe what she was seeing through her microscope. The cells perceived the stimuli as twice as strong—they talked more to each other; they were really blabbering. And, to keep it in colloquial terms, they had a lot more followers too, many more cells receiving their messages: a firework of signals, doubly as fast, visible from twice as far away. Miracle cells.

Everything is amplified? Henry was baffled. They redid the experiment, and got the same result: it wasn’t a fluke. How on earth could that be? Everyone spoke about a deficit, but they had found an excess, a strength not a weakness. These high-performance cells weren’t connected to each other by the usual streets but by veritable signal highways. Impressions and perceptions sped through them. Everything seen, heard, or smelled was amplified.

* * *

The baby is sleeping.

Mom opens the door.

Light falls onto the cradle.

She lifts the baby up, strokes his head. Her skin is slightly rough from bathing him, so he doesn’t catch a single germ.

She says the most loving words.

She disinfects her hands. And changes his diaper.

The baby cries.

You’re asleep.

You hear it slam.

You see it flash.

Thunder echoes in your head. Light stabs your eyes. The light fires into your tongue. You can taste the pain. It’s stamping toward you. Your whole world wobbles. It yanks you upward, your scalp in scraping pain.

Her voice hurts, screeching you feel to your fingertips. Your nose burns all the way into your head.

Your butt is in scraping pain.

You cry.

That was Kai’s life as a baby.

And then comes the day when the child starts to withdraw; when he turns away, wanders off, rejects everything. It often occurs slowly, almost imperceptibly.

* * *

Thirteen years of searching. Seven years since the diagnosis. It had been a long, hard journey: Kai’s eyes in the clinic, his silence in kindergarten, his tantrums, San Francisco, Lynda. After the diagnosis, with the mystery solved, he had continued to work in the wrong direction. When you ask the wrong questions, you get the wrong answers. Powerlessness, impatience. But who can be patient when their son is suffering? The search had become a hunt, and no one showed him the way. To the contrary, all the experts and textbooks had led him astray. How lucky he was that Kamila, another searcher, had joined him. And now it fell like scales from their eyes. They understood.

After thirteen years of trying, he finally understood his son. It was as if he had just gotten to know Kai. If only his son had been there with him, he would have hugged him. The hunt was over. Peace filled him.

And just as they sat there, with the sun sinking before their eyes, one thought after another rose to Henry’s head. Oh, that’s why Kai had done this and that. But not just Kai. He began to understand other children, like his friend’s daughter who suffers from autism. Every time she was supposed to shower, a drama unfolded. She resisted like a cat, scratching, biting, water-fighting. Her angry father scolded her: Can’t you just take a shower? It’s just a shower! Everyone showers! Don’t make such a fuss! It’s only water! But she wasn’t making a fuss. The drops of water felt like hot needles to her, torturing her. And since, like many autistic people, she didn’t talk, she responded with her hands and feet, trying to save her skin with desperate force. Was that so hard to understand?

Henry and Kamila realized that things were upside-down. Instead of dwelling on the supposed mind-blindness of autistic people, we should be discussing our blindness to their needs. Rather than talking about autistic people’s flaws, we need to focus on society’s flaws. “We say autistic people lack empathy. No, we lack empathy. For them.”

* * *

Their vacation was over. From then on, it was all about the article, typing and writing page after page in English and scientific jargon, supplementing their findings with numbers and tables, sources and studies. The Intense World Theory of autism. Translated into everyday language, the piece began like this:

Intense World Syndrome

Until now, no theory could explain autism in its varied manifestations. We are proposing such a theory. It is based on cell research and behavioral science.

Autism is multifaceted and ranges from disability to superability, with the latter being the exception. Most autistic people are considered stunted. Building on that assumption, established treatments have attempted to stimulate the brain.

We believe the opposite is true. The autistic brain is not stunted—it is too powerful. It is excessively interconnected and stores too much information. Autistic people experience the world as hostile and painfully intense.

Flooded with stimuli, the autistic person can only perceive the world in snippets. They focus on these snippets with excessive attention and a frighteningly good memory. This leads to savantism but also to social withdrawal and repetitive behavior.

This is important and points to a fallacy in many old studies. Scientists have often shown autistic people pictures of faces while observing the part of their brain that let them recognize those faces. If there was no discernible reaction, it was seen as supporting the scientist’s conclusion that their brain wasn’t working properly, i.e. autistic people suffered from a neurological deficit. It follows that one could cut out that part of the brain to see how they could live better without it. All that is wrong, says Henry. Many autistic people can’t recognize faces because their brain is overloaded, limiting its application. If you show an autistic child the faces of its favorite superheroes, instead of human faces, the apparently dead part of their brain is suddenly animated. It sparkles and rejoices like our brains do when we run into a long-lost lover. The feeling is indescribably intense. The child’s brain is so preoccupied with these sensations that it has no space for other faces, for people who aren’t part of its world.

If autistic people have a hard time dealing with other people, it is not because they cannot interpret their feelings or cues. Autistic people are neither oblivious to feelings, nor do they lack empathy.

In 2017, ten years after Henry and Kamila, Nature magazine published a study by a neuroscience institute in Boston, a partner university of Harvard, that used new technology to inspect what occurs in the amygdala when autistic people look someone in the eye. The scientists write:

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder often report that looking in the eyes of others is uncomfortable for them, that it is terribly stressful, or even that “it burns.” Traditional accounts have suggested that ASD is characterized by a fundamental lack of interpersonal interest; however, the results of our study align with other recent studies showing oversensitivity.

# # #

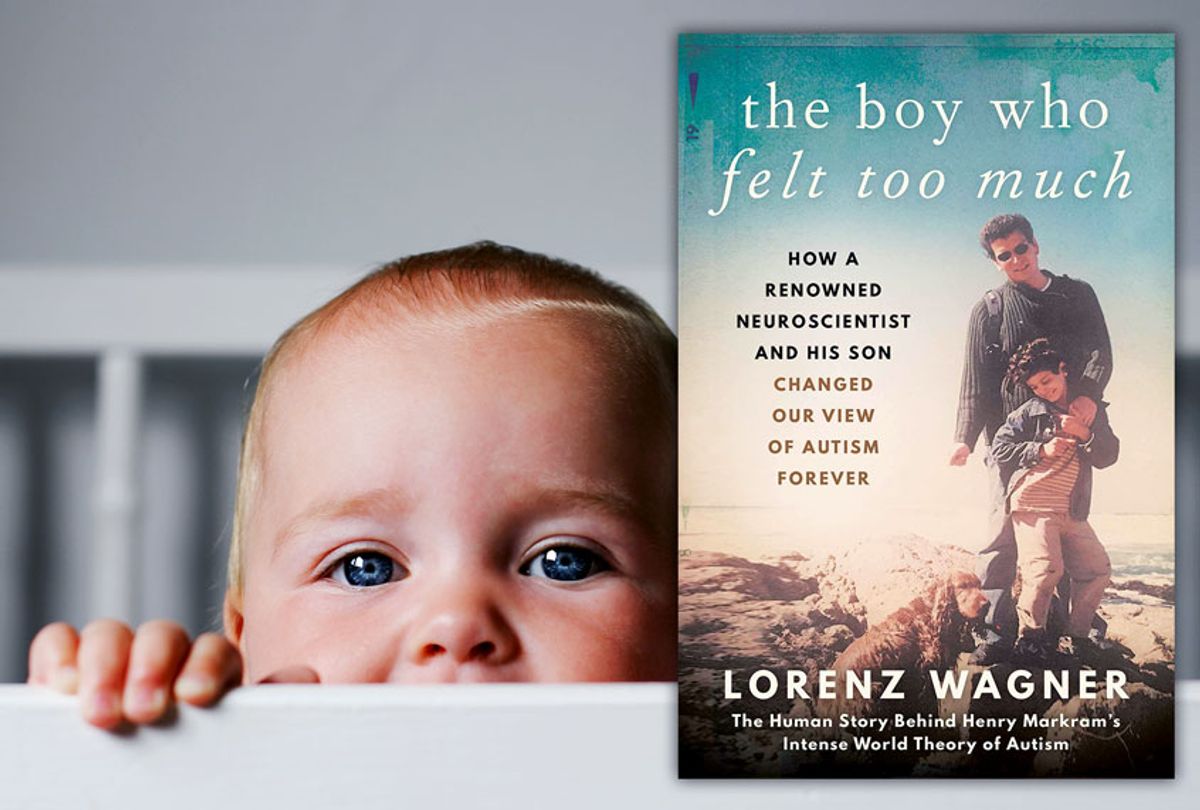

Excerpted with permission from "The Boy Who Felt Too Much: How a Renowned Neuroscientist and His Son Changed Our View of Autism Forever" by Lorenz Wagner. Copyright November 19, 2019 by Arcade Publishing, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Shares