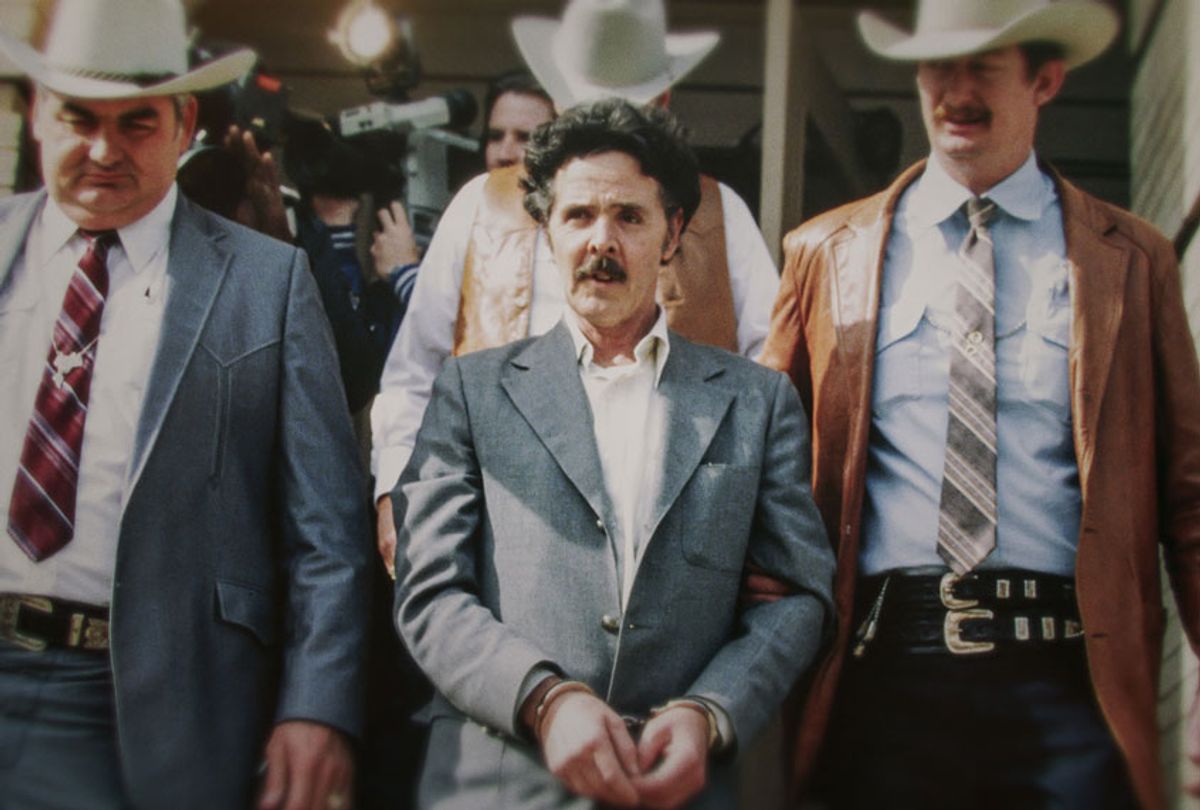

At one point in time, Henry Lee Lucas had confessed to killing over 600 people, an impossibly large number rendered even more incredible by the geographical spread of the supposed crimes.

The number had initially only been two, Frieda “Becky” Powell and Kate Rich, then ballooned to 100, then hundreds more while Texas law enforcement took him at his word, established “The Lucas Task Force,” and began closing these cold cases with abandon.

Unsurprisingly, as more evidence emerges and more modern investigation methods are developed, some inconsistencies between Lucas’ confessions and the cases emerge; in “The Confession Killer,” Netflix’s new limited docuseries, which is directed by Oscar-nominee Robert Kenner, these murders are then unsolved one by one — a typical true crime story in reverse.

Over the course of five deeply immersive episodes, through a mix of archival footage of Lucas (who died in prison in 2001) and current interviews with major players in the original investigations, viewers piece together Lucas’ troubled past and the reasons behind the officers' willingness to believe and perpetuate his self-proclaimed status as the country’s most prolific serial killer.

Lucas, who was born in Virginia in 1936, allegedly suffered an abusive childhood; his father was an alcoholic, his mother was a prostitute who forced Lucas to watch her have sex with clients, and made him cross-dress in public. Years later, Lee was convicted of killing his mother and served 15 years in prison.

After his release, he befriended a man named Ottis Toole, and the two drifted across the United States, eventually ending up in California, where he met Powell, Toole’s 15-year-old niece, and began working for Rich. It was eventually confirmed that he did, in fact, murder them both as he said when he first confessed in 1983.

But then the confessions just kept coming. In faulty interview sessions, during which police officers showed Lucas murder scene photography and files, Lucas parroted back information about the cases: how he had killed the women, what they looked like, where their bodies were eventually found.

Why? Put simply, the privileges that came along with being a serial killer — and an amiable one at that. Investigators agreed to give him a milkshake (strawberry, Lucas specified) for every confession he produced. He became the source of news stories and documentaries. Women wrote him letters. The prison minister was intent on his salvation. Lucas relished in the attention.

So in part, this is a story of a megalomaniac — a self-identified pathological liar — who went to extreme, almost laughable lengths, to keep the spotlight on him.

But perhaps more compellingly, “The Confession Killer” is about the shortcomings of the American criminal justice system and law enforcement. Officers cleared over 200 cases without any concrete evidence that Lucas was actually connected to the murders — no DNA remains, no new information provided by him that wasn’t found in the files officials had shared with him.

Despite this, very few of the cases have actually been reopened; that means that the actual murderers have gone free for years.

“I hated this dead man, but then the people that created it, I hate them more,” said a family member of one of Lucas’ alleged victims. “These are the people you trust to find the killer, bring them to justice and that wasn’t done.”

In “Confession Killer,” Kenner methodically lays out the faults in the system, taking no prisoners. He leaves viewers with a very clear message: while Lucas was a despicable human being, there’s true culpability found in the officers who so wanted to mark cases closed that they ignored the very real evidence to the contrary.

"The Confession Killer” is now streaming on Netflix.

Shares