I know we got the news on a Wednesday because my phone rang during Lilly’s guitar lesson. I never answer the phone while I teach, but this was an unknown number from Cincinnati. I thought maybe it was about a clinical trial for my father’s rare sinus cancer.

Instead it was my six-year-old’s agent, calling to tell me that Graham had been cast in a film he’d auditioned for two months earlier. Anne Hathaway had just signed on to star, opposite Mark Ruffalo, with Todd Haynes directing. My mind just about exploded.

I didn’t push my kid into acting. As someone who’s made a career in the arts, I would much rather my child work in finance or plumbing or truly, anything with a steady paycheck. Anything with health insurance. Anything to avoid the hustle. But Graham loves telling stories and playing pretend. I’d signed him up with a local theatre group to keep him happy, but I never expected he’d book actual jobs — and definitely not a Hollywood blockbuster with a bunch of A-listers.

After I got off the phone, the first person I wanted to tell was my dad Kenny, who was upstairs doing crossword puzzles. But the agency said I couldn’t tell anyone yet. Instead I apologized to Lilly for answering the phone during her lesson and went back to teaching the G-blues scale.

Graham and my dad — his “Grandude” — were the best of friends. Grandude had been living with us for four months, since my mom died from cancer, while he was being treated for his own bout with cancer.

The timing is never right for a cancer diagnosis, but my father’s had been a real What the hell, Universe? moment for him and for me, an only child. He got the “You’ve got cancer” call the same week he admitted my mom to hospice care.

Never one to complain, Dad carried on with his mantra — “It is what it is” — while going to daily radiation or chemo treatments during the last six weeks of Mom’s life. Graham and his little brother Angus kept us smiling through that awful waiting period until Mom finally drifted away, holding hands with my dad. It was the only time I’ve ever seen my dad cry.

Dad was never very emotional and definitely not talkative. He loved to brag about me and his grandchildren, but he rarely talked about himself.

Growing up, I never even knew much about my dad’s work. We weren’t a chatty family; we enjoyed our easy silences. I knew that he worked in hazardous waste disposal (which as a kid I’d secretly hoped was code for “mafia”), traveled a lot, and that he felt he was doing the world good by disposing of toxic chemicals safely.

He came to Career Day at school a few times, bringing a gas mask and hazmat suit and boring my classmates with talks of superfunds, landfills and 55-gallon drums. While I soared with pride, everyone else fell asleep. The pilot-father was way cooler than the chemist-dad, apparently. My dad was pretty cool, though. He read voraciously, could crush anyone at “Jeopardy!” and after retirement he launched a second career as a beloved bartender. (“Still a chemist,” he always said.)

The sinus cancer diagnosis felt like a cruel joke. Despite years of nosebleeds, headaches, and vision problems, doctors dismissed it as classic Ohio River Valley allergies, endemic to our area. Eventually the mass in his sinus grew so big that his cheek ballooned, and I insisted he get a CT scan, where we learned that the tumor had already invaded the bone.

Dad’s oncologists were not surprised to hear that his work history included hazardous waste disposal. Sinus cancers and cancers of the nasal cavity (grouped together in American Cancer Society research) are rare — only about 2,000 cases a year — and scientists say they can be caused by chemical workplace exposure. Dad was “an interesting case” (you never want to be an “interesting case”) but his team remained optimistic about treatment.

Four days after mom’s funeral, Dad had a large portion of his face and sinuses removed. Surgeons got clear margins, with no further treatment recommended. Good news at last! When the nurse asked who he lived with, Dad mumbled (because he had no teeth or soft palate), “No one. My wife died last week.” Facing an empty house with too many stairs, Dad moved in with us.

Graham was thrilled to have his best friend living with us. They adored each other. By age three, Graham was doing crossword puzzles with him. By four, he’d snuggle on the couch and read side-by-side with Grandude. Dad would teach him ridiculous vocabulary words, so Graham would come home and tell me I was “addled” or “grievous.” They went to train shows. They played “pirates” in the swimming pool for hours. Graham would beg to go visit Grandude at work behind the bar at the American Legion, where my dad would feed him maraschino cherries and Cheez-Its and let him play pull-tabs until I insisted it was time to leave. Now that Grandude was his roommate, there were constant giggles and treats.

That Wednesday of Lilly’s guitar lesson, I’d also driven dad to the oncologist for what we hoped would be the all-clear. A resident sauntered in and casually announced that the follow-up CT scans showed “a thickening above the eye.”

Not only had the cancer returned, it had returned aggressively.

Dad’s surgeon entered with an entirely different demeanor. This time he told dad there was “a lot to think about,” suggesting that while he was eager to do surgery, it would involve removing an eye, part of the nose and — no big deal — much of Dad’s frontal lobe. Just an eyepatch and a lobotomy, all with the hope my father, at 74, would even survive the operating table.

Perhaps Dad would like to travel first or think about his options.

We left the appointment with a stack of paperwork and silence.

That Wednesday afternoon my dad sat upstairs, doing crossword puzzles while I went into my basement to teach guitar.

When the call came in that afternoon telling me that Graham had been cast in the film, I wanted to run upstairs and tell my dad some good news for once. But along with the role came a non-disclosure agreement. There was silence during dinner, this time not so easy.

Fast forward a few weeks. I took Graham to Ohio to live in a hotel for a week while he filmed four scenes with an Oscar-winning crew. My dad knew something was up; suddenly I was on the phone with lawyers and mysteriously quiet about why Graham had to miss a week of school and why Dad would have to take an Uber to chemotherapy.

It didn’t take him and Google long to figure out what we were doing. There was only one film shooting in Cincinnati and IMDb said it was based on a New York Times article, telling the story of Rob Bilott, who sued DuPont on behalf of people exposed to hazardous chemicals disposed near the company’s Washington Works plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Once Dad figured out what we were doing, he let us in on a little secret.

“You know I worked there,” he told me.

Excuse me?

“DuPont. The Washington Works plant in Parkersburg.”

To me, now Graham’s film wasn’t just about a legal fight with DuPont, it was about a specific place: Washington Works, the exact plant where my dad had traveled to as a contractor, working with Teflon. It was the exact landfill and creek where my dad had filled 55-gallon drums with toxic chemicals.

When I asked him more about it during his last weeks, he said he had known he was dealing with toxic waste at the time, but he and his colleagues thought gas masks and hazmat suits were protective enough and that they were doing the community and factory work right by burying or incinerating the waste. No one had ever mentioned higher cancer risks to the workers.

This was Graham’s first time on a film set, but you’d never know it by watching him. Between craft services and the private tutor, Graham was in heaven. His own trailer, constant snacks and one-on-one attention? It was his extrovert’s dream.

Director Todd Haynes introduced himself to Graham warmly, kneeling down and smiling kindly with a handshake. Two actors introduced themselves as Mark and Annie. Graham was polite and quiet, knew his lines and sat on a couch on set while cats crawled over him playfully. He was wearing his red cowboy boots — a gift from my parents — because it had been raining, and the costume designer and director decided to leave them in the shot — I mean, what three-year-old doesn’t wear his cowboy boots with his pajamas?

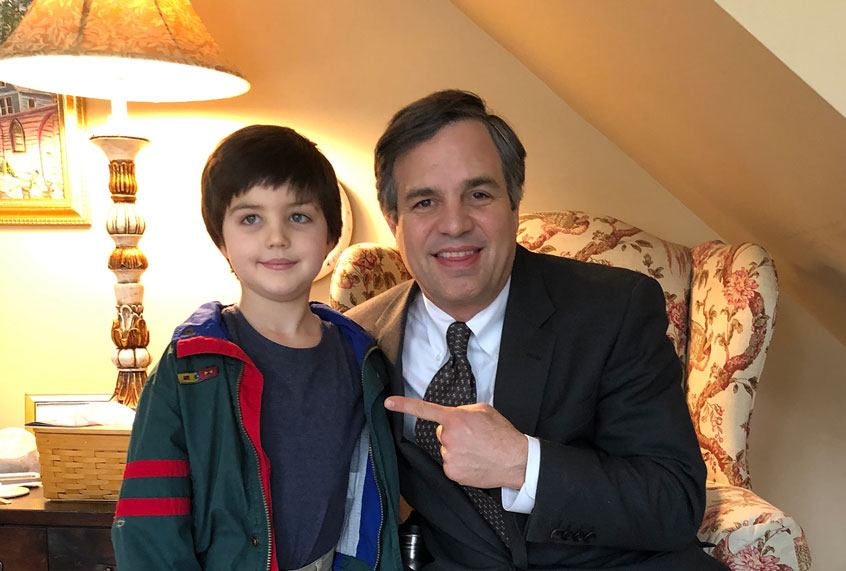

In the scene, the Bilott family is watching Barbara Walters report on the dangers of Teflon. Graham had a few lines, while he snuggled on the couch between Mark and Annie. I stayed out of the way. After three takes, they were finished. Graham quietly said bye and rushed off to craft services to raid the sugar supply.

We were swimming the hotel pool the next day when I told him that Grandude had worked at the exact plant portrayed in the script.

“Is that why Grandude’s got cancer?” Oh, Graham. “Mom, can I ask you something?”

“Anything, always,” I gave my standard answer to our script.

“What’s Teflon? And why would companies keep making it if they knew it was poisoning people?”

Nothing like a six-year-old to ask the hard questions.

Graham’s questions were heartbreaking. Even the SAG-AFTRA set teacher, who’d brought puzzles fit for a kindergartener, abandoned her lesson plans to join us in discussions of business ethics, chemistry and economics. Graham declared that everyone should know about the movie’s story. At one point he proposed, “They should get some famous people to be in the movie, you know, so more people will go see it.” (He had no idea who “Mark and Annie” were.)

Valentine’s Day was Graham’s last day of work. He and Mark were sitting around an old farmhouse on break, eating vegan snacks and doing crossword puzzles together. Graham made Valentines for people, from the PAs to the director. In his card to Mark, he’d wanted to tell him about Grandude, but told me, “It’s making me sad to write about it. Will you tell him, Mommy?” I added a little postscript thanking him for using his platform to tell the stories of the less powerful. Graham distributed his Valentines sheepishly during lunch and returned to his puzzles. I remember my optimism in writing to Mr. Ruffalo, “Dad can’t wait to see the film (we think he’ll make it).”

Life returned to normal after Graham filmed “Dark Waters.” He went back to school. Dad’s oncologists were pushing surgery as “the only curative option,” but also suggesting that he travel first. Even if he survived the operating table, he’d have a six-month recovery.

He’d wait a couple of months for the lobotomy. He had books he wanted to read. He wanted to see Angus turn three in March. He wanted to come on tour with me in Scotland in April. He wanted to see Graham do Shakespeare in May. And of course he wanted to see Graham in a Hollywood blockbuster that told the story of how he and so many others were allegedly poisoned by a chemical company. He was convinced he would see Graham at the Oscars.

By mid-April, we were on my Scotland tour, somewhere in the Isle of Skye, when it became clear that Dad was in the preactive phase of dying. He was either in denial, or was addled from a brain tumor, but he insisted he felt fine, only taking ibuprofen, despite grunting with every slow step, needing a cane to stand still, with a very obvious and nasty growth from his eye spread across his forehead. That music tour became more about quiet car rides through fairy pools, the slow ingestion of the beauty of the earth, sweeping landscapes and walking (or in my dad’s case, using a mobility scooter) in the footsteps of ancient kings.

Between long and not-so-easy silences, Dad would tell a story of his childhood or mine. He’d send a text to Graham when we passed Inverness Castle and Graham would reply, “Make sure you don’t get killed by Macbeth!” followed by 25 snake emojis and a Scottish flag. Dad would quietly sip a beer at a folk club in Edinburgh, smiling with pride as I sang. He’d go to bed early every night, his nosebleeds and his pain growing worse by the day.

We returned from Scotland on April 24, and Dad went straight to bed. He left only three times, not counting oncology appointments — twice to go to his favorite pub and once to see Graham in “Macbeth.”

After a difficult conversation with the neurosurgeon, we called off surgery and admitted Dad to home hospice care. He lay in his bed, both asking for Graham and not wanting Graham to see him like that. I asked Dad all the questions — about his childhood, his after-school jobs, his parents, my mom, his work. I asked him more about his time at DuPont. He grimaced with pain and anger, asking me to tell his story and never be afraid to speak out against injustice.

He died on June 10.

As for telling my Dad’s story, my son is taking that on, too.

Graham is seven now. He told his Grandude’s story at school recess, and in a way, through the beautiful film “Dark Waters.” He continues the family tradition of being an obsessive bookworm, sharing book reviews on his surprisingly popular Instagram account. He writes and directs short plays and films for neighborhood kids. He speaks out about environmental issues and is never afraid to ask a question.

Anything, always.