The only thing that a lot of the Washington journalism crowd could talk about or write about after Thursday night’s Democratic president debate was the fighting.

“Boy,” said CNN’s Chris Cuomo. After a “pretty mild” beginning, “it’s like they went to their respective corners and they got told to start punching.”

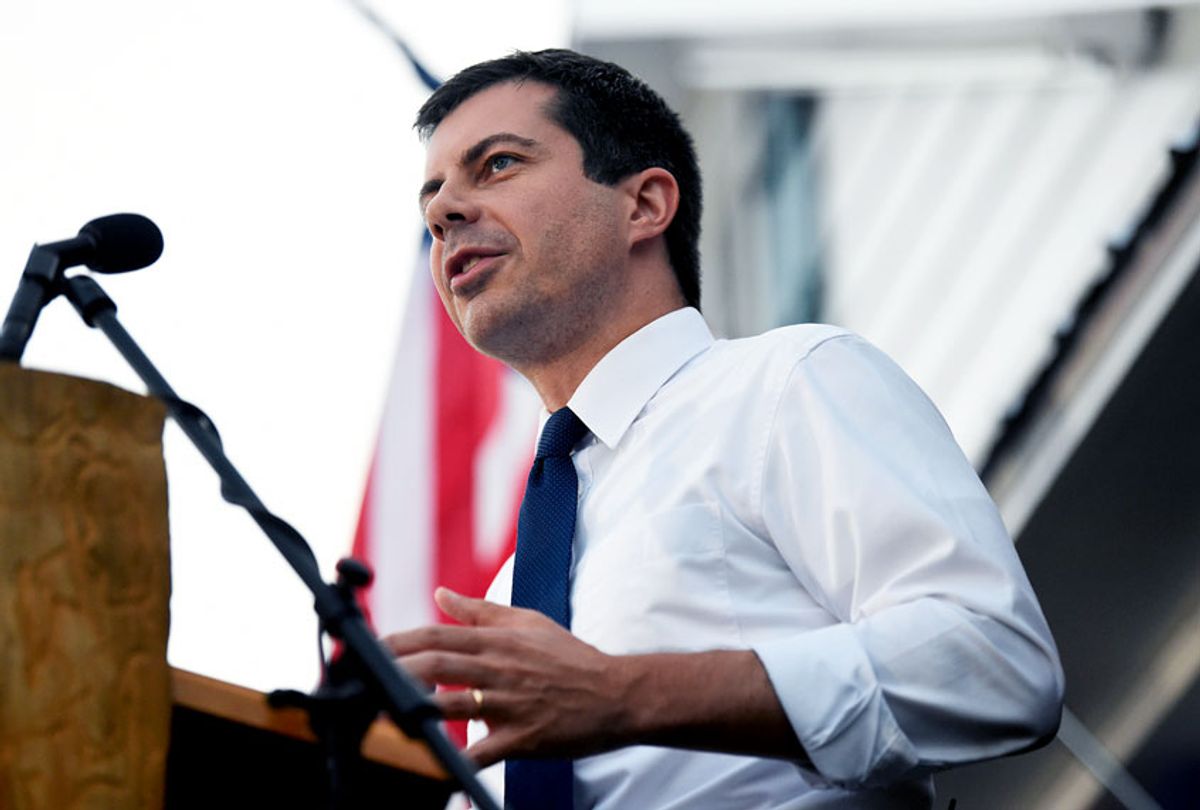

Pete Buttigieg “did get the incoming in the second half,” but “he was ready, he hit back and then some,” said Dana Bash.

There was talk of gloves coming off, pummeling, and slugfests, and that was just from Politico. Another Politico piece listed the “five most brutal onstage brawls” of the night, complete with a tally chart and boxing-glove emojis.

Dan Balz’s “analysis” at the Washington Post, headlined “A collegial start gives way to fireworks at sixth Democratic debate,” was really more of a play-by-play. He didn’t have a single word about what the fights were actually about for six paragraphs, and even then he wrote mostly about theatrics and who won. “In the moment, on the stage, it seemed advantage Buttigieg,” Balz wrote, without addressing the merits of the arguments.

Slate headlined Ashley Feinberg’s write-up: “Here Are Pete and Warren Ripping Each Other Apart; It took six months, but the debates are finally getting good.”

Enabling Trump

But here’s the thing: The media’s obsession with conflict over substance is one of the reasons Donald Trump won the election in 2016.

Trump fights a lot, and in an entirely unrestrained manner. So when it comes to 2020 presidential campaign coverage, if the media continues to focus on conflict, he will once again get the lion’s share of attention.

What’s particularly depressing about the lame coverage of the “wine cave fight” is that it actually offered an entrée into a hugely important topic as we approach 2020: Drawing the line on political corruption.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who sees fighting corruption as a defining issue against Trump, called attention to the contrast between herself and Buttigieg when it comes to whether the next Democratic nominee should engage in pay-for-play fundraising. From the transcript:

I made the decision when I decided to run not to do business as usual. And now I’m proud to have been in 100,000 selfies. That’s 100,000 hugs and handshakes and stories, stories from people who are struggling with student loan debt, stories from people who can’t pay their medical bills, stories from people who can’t find childcare.

Now, most of the people on this stage run a traditional campaign. And that means going back and forth from coast to coast to rich people and people who can put up $5,000 bucks or more in order to have a picture taken, in order to have a conversation, and in order maybe to be considered to be an ambassador.

The established, bipartisan practice of giving posh ambassadorships to big donors is a pretty good litmus test. As Warren explained:

I have taken one that ought to be an easy step for everyone here. I’ve said to anyone who wants to donate to me, if you want to donate to me, that’s fine, but don’t come around later expecting to be named ambassador, because that’s what goes on in these high-dollar fundraisers.

I said no, and I asked everybody on this stage to join me. This ought to be an easy step. And here’s the problem. If you can’t stand up and take the steps that are relatively easy, can’t stand up to the wealthy and well connected when it’s relatively easy when you’re a candidate, then how can the American people believe you’re going to stand up to the wealthy and well-connected when you’re president and it’s really hard?

Butttigieg mocked the idea of a “purity test” and declared: “I’m not going to turn away anyone who wants to help us defeat Donald Trump.”

But he avoided saying whether he would reward those big donors with access — which he has — or with favors, such as ambassadorships, later on.

The "wine cave" as symbol of corruption

A lot of the coverage dwelt on the now-infamous wine cave where Buttigieg had held his fundraiser — but, amazingly, whiffed on its extraordinary resonance as a symbol of corruption.

Several reporters noted, as an Associated Press story pointed out, that the “Hall Rutherford wine caves in the hills of California’s Napa Valley boast a chandelier with 1,500 Swarovski crystals, an onyx banquet table to reflect its luminescence and bottles of cabernet sauvignon that sell for as much as $900.”

But the most significant thing about the wine cave is that its owners, Craig and Kathryn Hall, are virtual poster children for buying Democratic politicians off.

As the AP story points out further down, Bill Clinton gave major donor Kathyrn Hall an ambassadorship to Austria. (A nice house comes along with that, including a four-acre garden):

Massive contributions to Democrats in the 1990s helped secure an Austrian ambassadorship for Kathryn Hall during Bill Clinton’s second term. Risky investments by Craig Hall, the chairman and founder of the Hall Group, during the savings and loan meltdown in the 1980s culminated in an over $300 million federal bailout and the resignation of House Speaker Jim Wright of Texas, a Democrat he turned to for help.

Federal regulators had been zeroing in on a series of Hall’s unpaid loans. To push back, the developer and bank operator turned to Wright, who was then ascending in the House leadership, to get them to back off, the AP reported at the time.

Wright held up legislation that would have given the struggling industry a $15 billion lifeline and told federal officials they had a “choice.” A few days later, the regulator overseeing some of Hall’s loans was replaced and the legislation moved forward.

This 1989 Washington Post story has more details.

Best practices

Over at the Los Angeles Times, Janet Hook wrote a solid article about the debate that didn’t focus on the fighting but rather on an issue closely related to corruption: electability.

Hook wrote that the candidates aiming to unseat Trump “turned with fresh urgency Thursday night to the question of who is best positioned to beat him at the ballot box next fall”:

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who largely shares that part of [Bernie] Sanders’ theory of the race, argued that an anti-corruption fighter like her is needed to provide clear contrast to Trump.

On the opposite side of the argument were the three more centrist candidates — former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind. Although the three differed from one another, especially in the case of Klobuchar and Buttigieg, they shared a view that defeating Trump requires an emphasis on pragmatism over ideology.

So it’s possible not to write about the debate like a bad TV critic.

More than that, it’s essential.

Shares