I had been in the Magic Kingdom for all of 15 minutes when I saw it out of the corner of my eye: the shirt. The worst shirt in the world, likely.

But before I tell you about the shirt, let me explain why, at age 32, I was visiting Disneyland in the first place. I had never been to any Disney property (or any other entertainment industry theme park), and had arrived under the auspices of writing an essay on what it would be like to visit the Happiest Place on Earth for the very first time as a childless thirtysomething.

Hence, by that point, everything I knew about Disneyland I learned secondhand: from watching movies or TV, mostly, that took place there. There was a 1993 "Full House" episode that my sister recorded on VHS, in which the Tanner family visits the Magic Kingdom, that informed my expectations. And of course, I had third-party knowledge of the Happiest Place on Earth from my elementary schoolmates' reports on their vacations. (That's how I knew what Space Mountain was.)

Beyond those data points, everything else I gleaned from pastiche. One formative Disneyland cultural reference that weighed on my mind was an old "Simpsons" episode in which the family visits Itchy & Scratchy Land, a Disneyland parody, only to find a surveillance state engineered to leech money from visitors. Upon entering, Homer purchases something called "Itchy & Scratchy Dollars." "It's like regular money, but — uh — fun," the cashier tells Homer, who accedes and buys $1,100 worth — only to find that nowhere in the park takes Itchy & Scratchy Dollars.

Hence, I entered Itchy & Scr — er, Disneyland — expecting the deepest pit of consumer hell. Because I had never been there as a child, I was a good candidate, I thought, to write about it as an adult — unencumbered by nostalgia. The rides, the food, the environs and the cheap souvenirs were entirely new to me.

But what I had not understood was that Disneyland wasn't merely a consumer spectacle; it was also a culture. Every city has its own fashion subcultures; Disneyland, and I presume Walt Disney World and the other Disney parks around the globe, apparently have their own rules of dress that apply only within the confines of the property. Hence, people visiting wear things there that they do not wear anywhere else. I did not realize this prior.

Often, "Disneyland style" takes the form of cheesy custom-printed t-shirts donned by families. There's a practicality to this, I suppose — if the whole clan is wearing the same pink shirt, it's a lot harder to lose each other in the crowd. These shirts say things like "Gonzales Family Disneyland Trip 2018," and then will usually be accompanied by a relevant graphic, like the outline of Mickey Mouse's head. The homemade, print-on-demand nature of these shirts guaranteed that they were not actually licensed by the Walt Disney corporation. (Indeed, on Etsy one can find hundreds of t-shirt printers that offer custom Disneyland family vacation t-shirts, all of them skirting copyright law.)

But there were also many guests — often adults without children — sporting hoodies or t-shirts that just read "Disneyland," or had a picture of Goofy or Mickey. It was very much like attending a sporting event in that regard: I pull my orange Giants shirt out of the closet when I go to see a San Francisco Giants game, as do many fans. Similarly, Disneyland attendees pull out their Disney shirt to go to Disneyland. The sports fandom and the theme park fandoms parallel each other, evidently.

It is curious that this doesn't apply to other realms beyond sports and Disneyland. When I eat fast food, for instance, I don't wear a themed t-shirt that says "Wendy's burgers"; when I go to walk my dog, I don't wear a special dog-themed outfit (though perhaps I should). If only we applied Disneyland fashion logic when dressing for all of life's happenings.

But Disneyland fashion is not merely t-shirts and hoodies. There's also the far more elaborate culture of Minnie skirts (as in Mickey's love interest). Many women — probably men too, although I didn't see any this visit — arrive at Disneyland engaged in a mild form of cosplay, clad in Minnie Mouse–inspired attire: a red skirt with white polka dots, a black cardigan, and a matching polka dot bow on their heads, generally.

There is something unusually quaint about this distinct Disneyland custom. I can think of no other fashion culture that transcends state lines so fluidly. An Alaskan, a New Yorker and a Montanan — all of different political stripes, and with little in common culturally — might all converge in Anaheim, donning similar "Family Disney Trip!" shirts or sporting the Minnie Mouse aesthetic.

Ten minutes after entering the park, I was taking this all in, when I saw a man with his family sitting on a bench. He was white, probably ten years older than me, with two young children and wife. His t-shirt featured the outline of Mickey Mouse's head. But rather than the mouse's face inside, there was an image of the Blue Lives Matter flag. I did a triple-take to make sure I had seen what I thought I had seen.

Why? What could possibly compel this shirt to exist? As I attempted to enjoy the train ride around the park, these questions turned over in my head.

The incongruity at the heart of the t-shirt is this: The Blue Lives Matter flag is a symbol of authoritarian obedience. It expresses opposition and denial of the notion that there is a systematic racialized bias in the way police treat African Americans, something that is empirically provable. The ideology of the Blue Lives Matter pseudo-movement is aligned with white supremacy and authoritarianism, in that it suggests that our increasingly militarized police force occupies some sacred place in America, immune to scrutiny.

So you have that; and then you have Mickey Mouse, a giggling, shirtless cartoon rodent.

To quote one of Mickey's avian coevals: One of these things is not like the other.

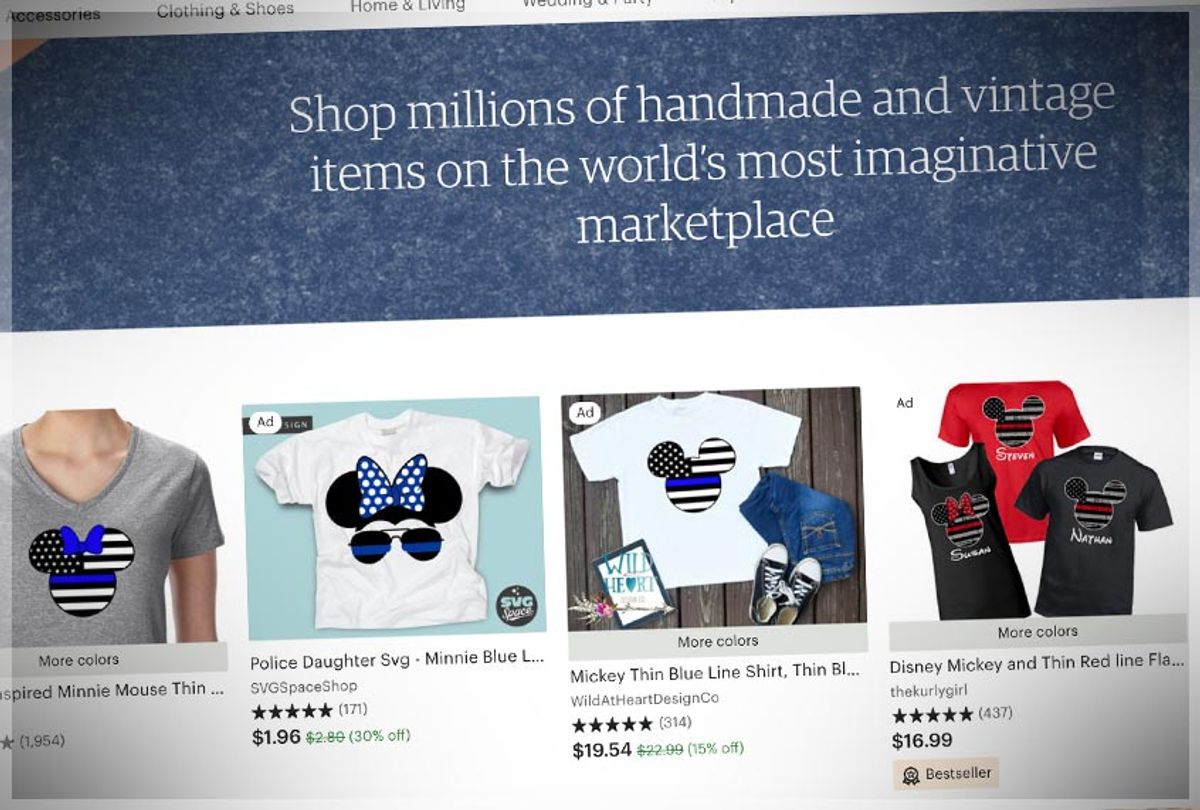

I saw four more of these shirts as I walked through the park that day. That meant it wasn't merely an anomaly. And indeed, when I got home, I searched on Etsy. There are dozens of sellers of this shirt. It goes by many names, including "Thin Blue Line Mickey," "Mickey Blue Lives Matter," and — most pithily — "Blue Lives Mickey."

My day at Disneyland ended, but questions over the shirt persisted. What were its wearers trying to convey? And what did this say about the state of American culture? I spent months turning over these questions in my head.

The transposition of logos and imagery from fiction onto political causes is not a new phenomenon. The Punisher skull, the logo of the Marvel Comics vigilante with questionable morals, has struck a chord among both troops and police. As David Masciotra noted in Salon last year, some police departments attempted to get the logo incorporated into their squad car decals — ironic, given that the character is, as Masciotra writes, a "fictional character who [r]outinely violates the U.S. Constitution, and appoints himself judge, jury and executioner when dealing with anyone under suspicion of illegal activity."

Mickey Mouse is not like The Punisher, surely. He doesn't enact vigilante justice and routinely violate the U.S. Constitution — as least, as far as I can remember from the cartoons I watched as a child. I consulted with my friend Jess, who accompanied me on my trip. What did they make of this? "Don't think of it as literally Mickey Mouse," Jess told me. Instead, Jess said, consider Mickey Mouse's head as a general symbol of Disneyland — of the kind of controlled, imaginary fantasy world that the theme park creates. Postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard observed this of Disneyland too. He called the surreality of Disneyland, and the image it projects, the "Disneyland Imaginary". As he wrote:

Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation. ... The Disneyland imaginary is neither true nor false: it is a deterrence machine set up in order to rejuvenate in reverse the fiction of the real. Whence the debility, the infantile degeneration of this imaginary. It is meant to be an infantile world, in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the "real" world, and to conceal the fact that real childishness is everywhere, particularly among those adults who go there to act the child in order to foster illusions of their real childishness.

Suddenly, everything clicked. The "imagineers" who build the world of Disneyland; the imagined idea of America that fuels violent right-wing fantasies about empire — these converge to form the heart of Blue Lives Mickey.

The contemporary American right is motivated by a fantasy of America, an idea of an idyllic past that never really existed. The maxim "Make America Great Again" encapsulates this. When was America great, and why? It is doubtful that many of us, accustomed to 21st century comforts, would actually enjoy the 1950s if we were to time-travel and live back then; and besides, the things from that era that made us prosperous — namely, the union movement, the post-New Deal welfare state, and the comparatively low cost of higher education — existed because of the left, not the right. Those who pine for an imaginary 1950s pine for something they saw on television, the stable, peaceable version of the midcentury that was depicted on film and in sitcoms from that eras. But those visions are not real: those are fantasy versions of America dreamed up by screenwriters. Yet they propel the right's idea of the "real" America.

In the same vein, Disneyland is a fantasy version of America, and particularly California. There are main streets, a simulated version of a national park, a faux-1950s era gas station, a 1950s diner. But these are all weak stand-ins for the real versions of these things, quite different from the real versions. Most tellingly, they all function as glorified souvenir shops: Disney takes the real markers of American civilization and history and makes fake versions whose main function is to document, through souvenirs, that one has been to the fake version. The real version of these things is uninteresting to Disney. There's no gas at Oswald's gas station, because there are no cars that can drive in that area; it's just a celebration of an imitation.

This incongruity really came to a head when I spotted, in the simulated version of a national park, a fake rock with a small box next to it. "Caution: Rodenticide. Keep children away," it read. How ironic to see this in a kingdom whose logo is a giant rodent. You like the fake rodent, and kill the real ones.

This is all to say that "the celebration of an imitation" also perfectly describes the Blue Lives Matter fantasy. The entire movement is just that — a fantasy about policing, authority and peacekeeping. Just as with Disneyland, the Blue Lives Matter fantasy is made real through television and film: police procedurals and films that celebrate the inherent goodness of police, their righteous mission, while taking a myopic view of criminality as something that is innate, rather than a result of social problems. One cannot underestimate the extent to which Hollywood is responsible for Blue Lives Matter, and for all our rosy feelings about cops, really.

Yet there's one more piece to the Blue Lives Mickey equation. How does one print those horrifying shirts without running afoul of Disney's lawyers? It turns out you can chalk this up to Silicon Valley "innovation."

Indeed, the Blue Lives Mickey shirts exist because of the contemporary internet marketplace and how it works. Disney is notoriously litigious; upload an image of Mickey, Minnie, or Goofy to the big on-demand t-shirt printing sites like CafePress or RedBubble, and you'll find the image deleted within minutes, and a copyright warning in your email. But there are platforms like Etsy and eBay that do not literally print t-shirts — they are marketplaces of resellers and small businesses who screenprint themselves, and use Etsy and eBay as storefronts. Like Airbnb and Facebook, these so-called platforms don't actually manufacture anything or own much beyond servers; they're just contractor factories who let anyone sell via these platforms, then take a cut of the proceeds. Thus, it is too difficult for Disney to systematically sue any of the thousands of screenprinters in assorted states who are making their own variants on Blue Lives Mickey and shipping them to Officer Buzzcut in Reno just in time for his family trip to Disneyland.

Baudrillard had one final, ironic note about the Disneyland Imaginary. He noted that all of Los Angeles, theme parks and film studios, was complicit in the creation of fantasies that fueled civilization. "Disneyland is not the only one," he wrote. "Enchanted Village, Magic Mountain, Marine World: Los Angeles is encircled by these 'imaginary stations' which feed reality, reality-energy, to a town whose mystery is precisely that it is nothing more than a network of endless, unreal circulation: a town of fabulous proportions, but without space or dimensions. ... As much as electrical and nuclear power stations, as much as film studios, this town, which is nothing more than an immense script and a perpetual motion picture, needs this old imaginary made up of childhood signals and faked phantasms for its sympathetic nervous system."

You could very well say the same thing about American policing. It relies on an imaginary idea of what it is, and what police do, in order to keep functioning. Mickey Mouse has been drafted into that fantasy.

Shares