For decades land use regulation across the U.S. has emphasized single-family houses on large lots. This approach has priced many people out of the quintessential American dream: homeownership. It also has promoted suburban sprawl — a pattern of low-density, car-dependent development that has dominated growth at the edges of urban areas since the end of World War II.

Now, however, Americans may be starting to question the desirability of a private house. In the past year, the Minneapolis City Council and the state of Oregon have voted to allow duplexes and other types of multi-unit housing in neighborhoods where currently only single-family homes currently are allowed. Democratic lawmakers in Virginia, who recently won control of their state’s legislature, are seeking to enact similar legislation. And several Democratic presidential candidates have included changes to zoning laws in their housing policies.

Headlines have predicted a housing revolution. But based on our research, we believe that while attitudes about suburban life may be evolving, the transition away from single-family zoning will be slow and difficult.

Sprawl’s heavy costs

Elected officials are rethinking single-family zoning because some of their constituents worry that single-family houses cost too much, are wasteful and can isolate people from their communities.

Many researchers have shown that single-family zoning promotes discrimination and exclusion. Our research focuses on its environmental impacts. Dozens of studies have shown that sprawl is energy-intensive, mainly for transportation; consumes too much land; degrades air and water quality; reduces species diversity; and contributes to climate change.

We have examined how Oregon’s land use policy affects residential density and Oregon’s housing affordability crisis. Oregonians are known to be progressive and environmentally conscious. They hate density because they value privacy and space. But they also hate sprawl because it consumes valuable agricultural land.

In short, Oregon would seem to be the ideal starting point for policies curbing single-family zoning. One of its 19 statewide land use planning goals, which were adopted in the early 1970s, addresses housing and requires cities to include many housing types. But exclusive single-family neighborhoods still dominate Oregon’s landscape today.

Single-family nation

In the early 1970s, in what came to be named “the quiet revolution in land use control,” some states started taking back authority over zoning that they had ceded to cities and towns. In 1973, Oregon created “urban growth boundaries” — a line of demarcation between urban and rural land uses — around each of its cities, along with other measures to contain growth and prevent sprawl.

Our research shows that this approach has helped contain urban growth and promote more efficient land use. Single-family density in urban growth boundaries, as measured by single-family housing units per acre, has consistently increased since the zones were created. Statewide, single-family density increased 22% from 1993 to 2012.

[Oregon Imagery Explorer](http://imagery.oregonexplorer.info/ )

Still, sprawl exists inside urban growth boundaries. We have found that land exclusively zoned for single-family homes can hold only a maximum of eight to ten units per acre. And as demand for houses exceeds supply, lower-income families are pushed into cheaper areas far from their work. Up for Growth, a national coalition that advocates for denser development, estimates that only 89 housing units were built in Oregon for every 100 households formed from 2000 through 2015.

In short, housing is getting more expensive. A 2019 Harvard study concluded that the supply of low-cost rental units (under US$800 per month) in Oregon decreased by 44% between 1990 and 2017. Today 63% of Oregon’s housing is stand-alone houses or detached single-family units.

Housing struggles make smaller dwellings more desirable

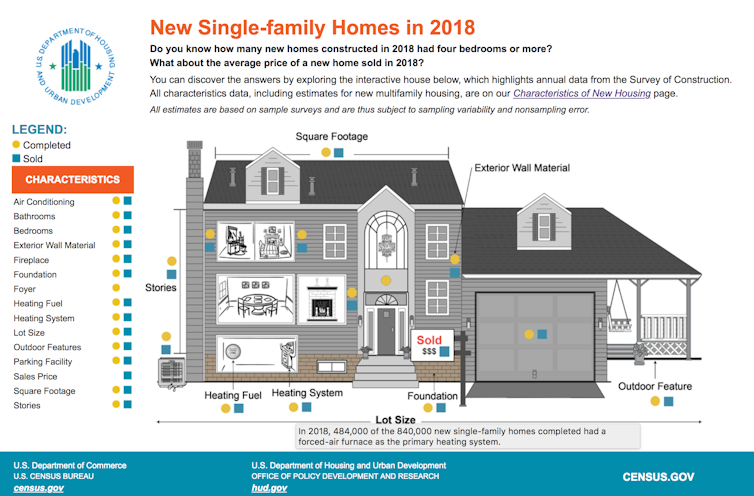

These issues aren’t limited to Oregon. According to the Harvard Joint Center on Housing, 47% of renter households nationwide are paying more than 30% of their income in housing costs. And new residential construction remains below pre-2008-2009 recession era rates.

Between 2000 and 2015, the U.S. underproduced 7.3 million units of housing, meaning that families across the country are struggling to find housing that is affordable and available. This shortage spanned 22 states and the District of Columbia.

Public officials are recognizing that allowing only single-family houses also creates equity problems. Single-family zoning segregated neighborhoods after World War II by excluding African American families, who could not afford to buy single-family homes, from middle-class white neighborhoods.

U.S. Census

Today demand for smaller, connected houses — including duplexes, triplexes and quadplexes — within walking distance of services is increasing. People like living this way, but as architect and urban designer Daniel Parolek has shown, regulatory barriers deter builders from producing more of these types of housing, which he calls the “missing middle.” As Parolek points out, many of the diverse housing types that are common in older neighborhoods, such as duplexes and triplexes, are illegal under most current zoning codes.

A modest but important start

All of these factors helped drive Minneapolis and Oregon to move away from single-family zoning and allow more housing types. But for all of the attention that these actions have received, we predict that they will have modest impact.

Housing markets are complex and are affected by much more than zoning. One key question is whether costs will decline if policymakers encourage construction of diverse “missing middle” dwelling types.

But this does not mean that changing zoning policies is misguided. Promoting construction of broader ranges of housing creates more vibrant neighborhoods, reduces conversion of farm and forest land for suburban development, reduces infrastructure costs and provides more equitable housing opportunities for all.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

Robert Parker, Co-Director, Institute for Policy Research and Engagement, University of Oregon and Rebecca Lewis, Associate Professor of Planning, Public Policy and Management, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares