The new year brings so many tantalizing possibilities, including a resolution to read more – whether it’s to fulfill a shiny new book challenge for 2020 or just fill your brain with something more nourishing than the noise from the depressing news cycle and social media. This is a chance to make a new author discovery, enjoy the next bestseller, or even possibly change your life. It’s a new decade; bring on the books!

January offers up some tantalizing books from familiar names, such as the late Zora Neale Hurston’s collection of lesser-known short stories “Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick” (Jan. 14) and William Gibson’s new sci-fi thriller “Agency” (Jan. 21)

The following seven novels are an eclectic mix of tales that explore how one’s identity can be built from trauma, the lies we tell ourselves or accept from our family, and society’s strictures upon race and gender.

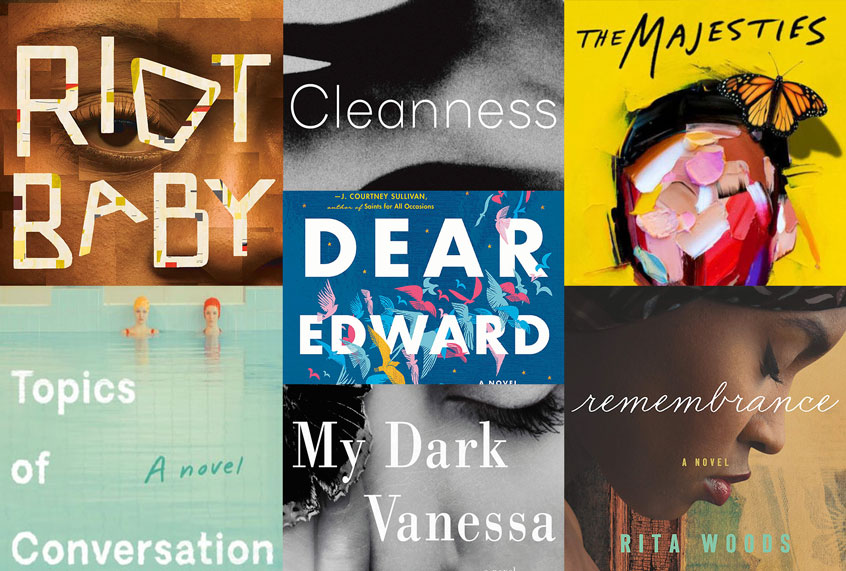

“Dear Edward” by Ann Napolitano (The Dial Press, Jan. 6)

Edward Adler wakes up in a pastel-colored bedroom. Looking around, it’s a little too soft for a 12-year-old boy, yet it’s simultaneously darkened by its original purpose: a nursery for the child Edward’s aunt and uncle never had. It’s a simple moment, but one that signifies so many things — so many lost dreams — and causes readers to ponder the reality that one morning you could wake up and confront that your life may not contain all that you planned.

“Dear Edward” begins with a freak accident. Following a pilot error amidst unprecedented weather conditions, Airbus A321 enters a tailspin and plummets to the ground somewhere in Colorado. Edward is the only survivor. Along with losing his family — a screenwriter mother, a mathematician father, a near-idolized older brother — Edward also loses the promise of continuing his childhood in California, where his mother had just gotten a job.

In alternating chapters, we get a glimpse into the lives of some of the passengers on the doomed flight, as well as Edward’s new life with his mother’s sister and her husband. Make no mistake, stretches of this novel are bleak; we’re introduced to new characters over and over with knowledge that we will once again have to experience their deaths (something that is cunningly mirrored by author Ann Napolitano in her writing about how tragic events are covered and recovered in the age of social media and 24-hour news cycles). Edward tries to block out these images, while also grappling with survivor’s guilt. To cope, he seeks “to remember nothing, think nothing, until all that exists is a flatness — a flatness that he now identifies as himself.”

But Napolitano provides respite from the emotional desolation of “Dear Edward” by writing in moments of extreme tenderness, specifically in her portrayal of Edward’s relationship with his precocious pre-teen neighbor, Shay. She is decidedly odd, but obviously so is Edward. She reminds him of this early in, and occasionally throughout, their friendship. Because of his survival, Shay says, he’ll never be “a normal kid.”

The book vacillates between heartbreaking and heartwarming (perhaps grounded more soundly in the former), but is a stark survey of how random occurrences and accidents can shatter our future plans. — Ashlie D. Stevens

“Topics of Conversation” by Miranda Popkey (Knopf, Jan. 7)

In her debut novel, Popkey brings a fierce insight and honesty to the story of a woman whose emotional growth is filled with fear, intellectual curiosity, self-loathing, and violence. Set over the course of 17 years, the unnamed narrator drops in on various moments in her life to chronologically relate a brief event or conversation – some life-changing, some seemingly uneventful – that builds on the chapter before. While occasionally disorienting as the reader catches up to what’s happening from the previous few months or years, the cumulative effect is to see what is familiar, the patterns in her life. And to see them is to judge them as various relationships fall away or are challenged through her self-destructive actions.

At only about 200 pages, the novel is a compact but intense experience partly because it is told in first person. The narrator meanders often, with quoted dialogue blending into descriptions of what a character is doing or wearing with hardly any nods to quotation marks or other visual dividers in between.

Popkey thrusts the reader into that moment in sun-soaked Italy or an avant-garde artist’s exhibit involving a swimming pool with confidence, but the narrator herself is anything but. While it’s clear to witness the sharpness of her mind, she also relates these events with a practiced detachment that can sometimes make the reader either want to shake her or begrudgingly identify with her.

“There is, below the surface of every conversation in which intimacies are shared, an erotic current,” Popkey writes in one telling passage. “This is the natural outcome of disclosure, for to disclose is to reveal, to bring out in to the open what was previously hidden. And that unwrapping, that denuding, is always, inevitably sensual.”

In many ways, “Topics of Conversation” is a quiet novel, an observation of a woman’s life and eventual awakening to her own patterns. And yet, below the surface of Popkey’s prose beats that intimacy that she has alluded to. And whether the reader is intrigued or repulsed, the force of that seduction remains long after the last page is read. – Hanh Nguyen

“The Majesties” by Tiffany Tsao (Simon & Schuster, Jan. 7)

Why would one woman commit mass parricide by poisoning 300 relatives, family friends, and herself at what should’ve been a joyous celebration? That’s what Gwendolyn Sulinado, the sole survivor of the event, is wondering as she recovers from her sister Estella’s horrifying act.

And thus begins Tiffany Tsao’s novel in which Gwendolyn, aka “Doll,” must search her past for clues to her sister’s state of mind leading up to the event. This takes the reader on a journey over decades and across seas, from the wealthy mansions of Jakarta and college campuses of Melbourne, to the California coast and Paris fashion week.

Despite the story’s globe-trotting nature, the mystery ultimately digs into the secrets that come with family and corruption. As more of Estella’s past is revisited, the reader will familiarize themself with the dark, morally bankrupt side of how the super-wealthy overseas Chinese (such as the ones in “Crazy Rich Asians”) make and keep their money, especially during the Krismon, or 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Amidst these real-world events is an element of the fantastic and an unexpectedly provocative showcase for – of all things – entomology. And that’s just part of the surprises in store for Tsao’s unusual novel that saves the ultimate toxic twist for the end. – H.N.

“Cleanness” by Garth Greenwell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Jan. 14)

Garth Greenwell follows up his acclaimed debut novel “What Belongs to You” (National Book Award longlist, among many accolades) with another stunner featuring his unnamed narrator who teaches English to college-bound high schoolers in Sofia, Bulgaria, while navigating the possibilities and contradictions of connection and alienation, risk and reward, and the boundaries of his desire.

In “Cleanness,” Greenwell’s teacher falls in love with the Portuguese college student R. Their tender and fragile relationship forms the centerpiece of the novel, bookended by the narrator’s explorations of power, surrender, joy, ethics, and fear, in sex and in his vulnerable identity as a gay man in a city where the visible queer community faces open hostility.

Intensely erotic, brimming with tension, sublime on the sentence level and pleasurably painful in its articulation of both yearning and ambivalence, “Cleanness” is more than a beautiful closing, perhaps, to the narrator’s Sofia story. With a follow-up this strong to one of the best books of 2016, Greenwell establishes his place firmly in the center of our must-read shelf. — Erin Keane

“Remembrance” by Rita Woods (Forge Books, Jan. 21)

“Remembrance” is not a book of suspenseful plot twists and shocking revelations. Critical details are dropped early and subsequent action is contemplated at length. This isn’t necessarily a mark against the novel, but think of it as a speed limit, of sorts, on a long-distance road trip. Buckle up, set the cruise control, and drive. There are no high-speed chases, but more often than not the scenery is worth it.

Woods’ debut novel takes place in three distinct time periods: modern-day Ohio, antebellum New Orleans, and revolutionary Haiti. In each of these time periods, we meet black women grappling with crises, some personal and some social. At the core of it all is a multigenerational saga of slavery and otherworldly power.

We begin with Gaelle, a modern Cleveland nursing home worker who is caring for a resident known only to staff as Jane Doe. Her background is a complete mystery, though she seems to understand the Creole that Gaelle speaks to her. But then one day Jane Doe abruptly grabs Gaelle, pulsing with a hot, magical energy — an energy that Gaelle too possesses. From there, it becomes apparent that their stories are connected, but just how deeply (and to whom else they are tied) remains to be seen.

“Remembrance” is a thoughtful 2020 read for fans of our August 2019 recommendation, “She Would Be King” by Wayétu Moore. — A.S.

“Riot Baby” by Tochi Onyebuchi (Tor/Forge, Jan. 21)

Equal parts provocative and riveting, “Riot Baby” is what all speculative fiction should strive to be: wholly captivating. The titular character is Kevin, a black boy born in 1992 Los Angeles, just hours after the courts acquitted the cops that beat Rodney King and the city erupted in violence. Over the book’s span of 28 years, it seems that society is hurtling closer and closer to dystopia, but Kevin is locked onto one goal: protecting his sister, Ella, from herself.

You see, Ella has a “Thing.” She can see things that haven’t happened yet. Her consciousness exists on multiple planes. She knows what her classmates will be when they grow up; she knows which ones won’t make it to adulthood.

But Kev can only protect her for a while. Then the roles are reversed. As a teenager, he is savagely beaten by law enforcement and is arrested despite committing no crime. He’s sentenced to eight years in Rikers. While incarcerated, Ella visits him. Sometimes in person, and sometimes psychically — using her powers to allow him a glimpse of life outside prison walls where police brutality is on the rise, and encouraging him to find hope for a better future in (not despite) his justified anger. — A.S.

“My Dark Vanessa” by Kate Elizabeth Russell (William Morrow)

UPDATED: The publication date for “My Dark Vanessa” is March 10

Calling “My Dark Vanessa,” the electrifying debut of Maine native Kate Elizabeth Russell, “a #MeToo novel” — as it surely will be tagged — would not be not wrong, exactly. But it would be an incomplete assessment of a book that feels both necessary for this exact cultural moment and decades in the making, answering Nabokov’s “Lolita” by asking the urgent question of what happens then to a Lo who lives, haunted by what was done to her and also unable to name it for what it was.

When Taylor, a graduate of a bucolic New England boarding school, announces in the thick of the 2017 reckoning that a longtime English teacher had sexually assaulted her when she was a student, another former student now in her 30s — narrator Vanessa — immediately takes her old teacher’s call, reassuring him that she won’t allow herself to be “roped into” the narrative too. As Taylor tries to enlist Vanessa as an ally while an enterprising journalist seeks to make her a source for an exposé, Vanessa goes through her own private reckoning with her past. Russell takes us back and forth through Vanessa’s point of view, from her sophomore year as a 15-year-old misfit scholarship student groomed for an “affair” by charismatic 42-year-old Jacob Strane that blows her entire world apart and continues to define it up through the unfolding of the #MeToo movement. Vanessa struggles with how to make sense of all that happened to her now that she might finally not be seen, or need to see herself, as culpable — or worse, as the villain of the story.

Crucially, Russell makes Vanessa an unreliable narrator of her own knowledge, enthusiasm and agency, but never on Strane’s actions and manipulations, which are unambiguous to the reader if not to her. In this way, the fictional Vanessa offers valuable insight on how and why survivors of sexual abuse or trauma who are inconsistent in their accounts or who are reluctant to speak out or to see themselves as victims might process, explain, and define what happened to them differently from what’s expected. And Russell doesn’t restrict her damning gaze to Strane — this is not a story about one bad man and a girl he harmed, but rather an entire system that perpetuates these damaging cycles because of whose perspective must be privileged in order for the whole structure to remain standing. — E.K.