In 1994, 85 people died in a bombing at the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, or AMIA. The attack on the Buenos Aires Jewish community center was the largest terrorist attack in the Western hemisphere until 9/11. Prosecutor Alberto Nisman investigated the attack, and potential ties to government corruption, for nearly two decades, before he was found dead in a locked apartment the day before he was to reveal his findings.

While initial media reports suggested that Nisman died by suicide, the new Netflix documentary series, “Nisman: The Prosecutor, the President, and the Spy” revisits the case. In an interview with Variety, director Justin Webster — known for his work on the Emmy-winning “Six Dreams” and HBO España’s “The Pioneer” — said he hoped the series would shed new light on the conditions of Nisman’s death.

“‘The Prosecutor’’s thrust is to reach some more clarity on a subject that is so difficult, and so complex. As often happens, in lots of cases, they play out over a long period of time,” Webster said. “People have strong opinions about it, but they don’t really know the whole story.”

But over the course of six meticulously detailed and comprehensive episodes, it becomes apparent that the “whole story” isn’t about whether the trigger was pulled by Nisman or someone else; it’s about parsing through nearly 50 years of intergovernmental (and international) history and connections to understand how Nisman’s death could have occurred in the first place and what it signified to the people of Argentina about the integrity of their legal system.

While classified as a true crime series, “The Prosecutor” is not alone in this approach turning the camera from the crime itself to the bigger picture. It’s part of a movement within the genre wherein the narrative is less about solving a mystery and more about turning the magnifying glass on the legal proceedings that surrounded it; a sort of “true criminal justice” designation as opposed to “true crime.”

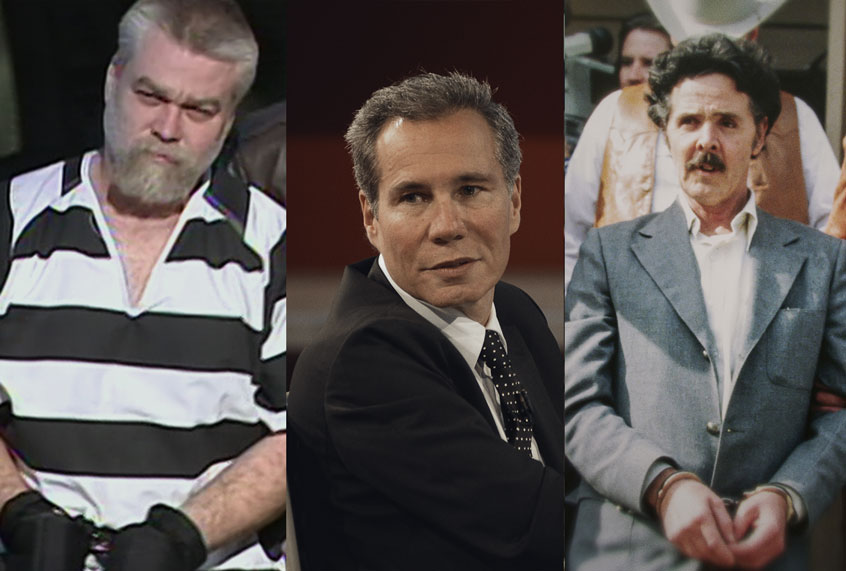

“Making a Murderer,” which premiered on Netflix in 2015, had glimmers of this. The series opens by telling the story of Steven Avery, a salvage yard owner from Manitowoc County, Wis. He served 18 years in prison for a sexual assault he didn’t commit, then was exonerated by DNA evidence in 2003.

Two years later, just as Avery was gathering steam for a civil lawsuit against the county for $36 million in damages for his wrongful convictions, he and his 16-year-old cousin, Brendan Dassey, were arrested (some would say conveniently) in connection to the murder of local photographer, Teresa Halbach. They are both currently serving life sentences.

The series became an instant sensation, I think, in part, because of its compelling (in not particularly unbiased) argument that personal vendettas by law enforcement and government officials sullied the actual investigation of the case. Avery’s attorney, Kathleen Zelner, accused Manitowoc officials of evidence tampering after a vial of Avery’s blood — which had been stored in an evidence locker since the 1985 trial — was found with broken container seals and a puncture hole in the stopper.

This means that it could have been used to plant his DNA at the crime scene.

By Season 2 of “Making a Murderer,” the series creators and Zelner will have at least some viewers convinced that Avery was framed for the murder and that Dassey had been coerced into confessing to the crime; but I would argue that nearly all viewers would agree that some level of prosecutorial misconduct existed within the Avery trial.

This upends the roles of typical true crime series a bit. Where once there was a clear delineation between the good characters (the victims and law enforcement) and the bad character (the killer), stories like “Making a Murderer” complicate the narrative.

This is something that is absolutely on display on the 2019 documentary series, “Confession Killer.” It starts with a salacious premise — at one point in time, Henry Lee Lucas had confessed to killing over 600 people. This would have obviously made him the most prolific serial killer who had ever lived.

The number had initially only been two, Frieda “Becky” Powell and Kate Rich, then ballooned to 100, then hundreds more while Texas law enforcement took him at his word, established “The Lucas Task Force” and began closing these cold cases with abandon.

Unsurprisingly, there were some inconsistencies in Lucas’ stories, wherein the impossibly large number of victims and the geographical spread of the supposed crimes just didn’t add up. So why did law enforcement take him at his word? Simple: to close cases.

While Lucas is an interesting character study — here we have a man who strove to keep himself in the limelight by confessing to an absurd amount of grisly crime — what makes this series infinitely more evocative is in its dissection of the shortcomings of the American criminal justice system.

As “Confession Killer” concludes, we find that officers cleared over 200 cases without any concrete evidence that Lucas was actually connected to the murders; there are no DNA remains, no new information that wasn’t in the original police files. Despite this, very few of the cases have actually been reopened; that means that the actual murderers have gone free for years.

It’s series like this — much like “Nisman: The Prosecutor, The President & The Spy” — that makes one realize the delineation between good guy and bad guy is often infinitely more complicated than we’d like to believe; these are the series, too, that show that good true crime is not just about retelling shocking events, but about speaking truth to power.

“Nisman: The Prosecutor, the President, & the Spy” is currently available to stream on Netflix.