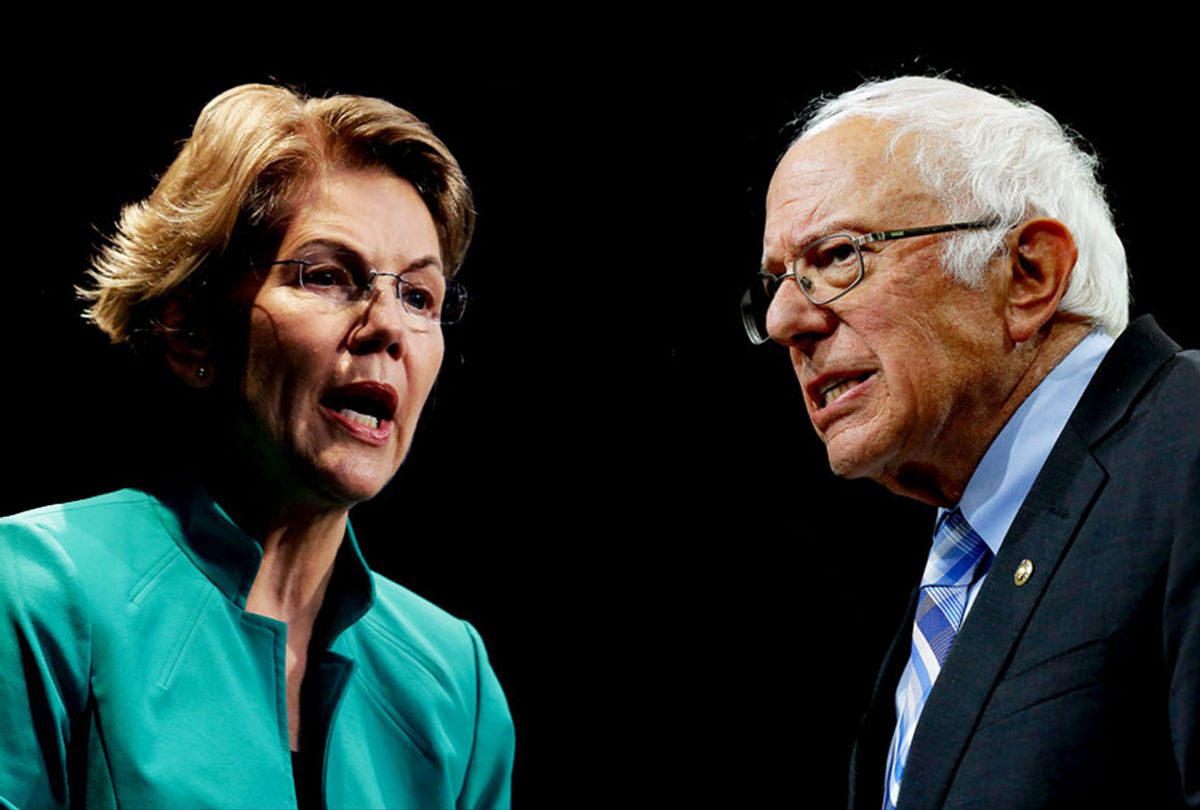

It started as garden-variety tensions between two campaigns competing for the same voters. Then it exploded into a testy exchange during — and after — Tuesday night's Democratic presidential debate, when Elizabeth Warren refused to shake Bernie Sanders' extended hand. By Wednesday morning, Sanders' supporters online were using a snake emoji to symbolize Warren, and it wasn't hard to decode the sexist reference to the original betrayal in the Garden of Eden.

The fight had a little of everything: an intra-family dispute about sexism on the eve of the Iowa caucus that allowed Democrats to fight, once more, about the lessons of the 2016 race and to relitigate Bernie versus Hillary. The two candidates' history of mutual respect was seemingly cast aside.

National political outlets couldn't get enough. "The Warren/Sanders feud just got way uglier," screeched CNN. New York magazine framed it as a boxing match: "The Sanders/Warren, he said/she said showdown over sexism." Talking Points Memo told the "story behind the tense non-handshake." NBC fretted that the Sanders and Warren camps were "so worried about reliving 2016, they're recreating it."

Nevertheless, as the negativity and bitterness spiraled out of control, it threatened to fracture not only progressives but Democratic unity this fall, should either Sanders or Warren capture the nomination and these intense feelings linger.

What did Sanders and Warren discuss at that meeting in 2018? Who misinterpreted whom? It shouldn't matter. This is no way to select a nominee. Sanders and Warren are natural allies. Their supporters share overlapping policy agendas. They seem to like and respect each other personally. They're only fighting this fiercely over ephemera to try and move a handful of voters from one column to the other ahead of a tight four-way race. Our very winner-takes-all election structure not only encourages this inane behavior, it almost necessitates it.

The problem isn't the people. It's the all-or-nothing nature of the system. It is time to change it.

Just imagine how different Sanders and Warren might campaign if we elected our leaders with ranked choice voting, and voters had the power to select their backup second and third choices to count if their first choice couldn't win. Sanders and Warren wouldn't be at each other's throats, and we wouldn't be seeing their supporters battling with snake emoji and unleashing powerful emotions about gender still raw from 2016. They'd be campaigning as a team, urging followers to support the other as a second choice.

Different incentives lead to a different kind of race. When candidates also compete to be second and third choices, they play nicer and engage in less negative campaigning. They need to appeal to supporters of other candidates. They can't risk alienating them. Numerous studies have shown that RCV elections not only produce more positive races, but that voters and candidates come away happier with the results.

Sometimes the candidates even campaign together. In San Francisco, which elects its mayor with RCV, two candidates formed a coalition in 2018 and asked voters to rank them first and second, in whichever order they pleased. That same summer, Mark Eves and Betsy Sweet, two progressive Democrats seeking to be the next governor of Maine, ran a unique joint ad ahead of the state's primary in which they endorsed each other for second place. "We are competitors, but we have been longtime allies," Eves said, as the two stood side by side. "We believe that the only way Democrats win in November is if we elect a strong progressive, and you've got two of us right here."

What a difference in tone. The positivity leaves much more room to discuss issues and ideas. It forces candidates to discuss their records, and their opponents, far more constructively. It makes it possible to emerge from a primary campaign unified, rather than bitter and bloodied. And it ensures that the winner is always the candidate with the widest support, that everyone can ultimately get behind.

The good news is that five Democratic presidential primary states will be using RCV this spring, one for early voting and four for the entire primary. New York City just amended its charter to use RCV for most city elections. Maine expanded its use of RCV to presidential elections. Cities and townships nationwide, from Massachusetts to Utah and New Mexico, have recognized that RCV gives voters more choice and incentivizes politicians to campaign — and govern — with everyone in mind, not just an influential base.

It's proof that we can have better elections. Our primaries shouldn't remind us of mom and dad getting into a fight. They shouldn't be covered as dramatic entertainment, like "Marriage Story" or "Kramer vs Kramer." Sanders and Warren decided to club one another because our electoral system made such ugliness make sense. There's time to flip the script — and build a healthier democracy.

Shares