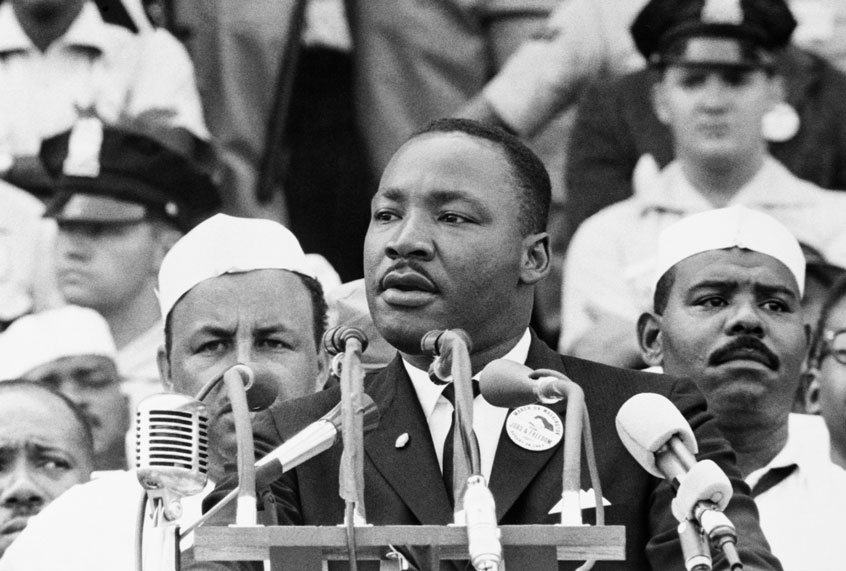

“We also realize that the problems of racial injustice and economic injustice cannot be solved without a radical redistribution of political and economic power.”

—Martin Luther King Jr., 1967

This Martin Luther King Jr. Day comes as moderate Democrats, falling in line behind former vice president Joe Biden, are warning that the party risks re-electing Donald Trump if it nominates too radical a candidate for president — by which they mean someone like Senators Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren.

This so-called moderate world view is underpinned by the belief that, over the arc of this nation’s history, we have been striving for and realizing a “more perfect union” through disciplined incrementalism and market capitalism.

Some pundits extol this as the great virtue of American moderation.

And yet, a glance at Martin Luther King Jr.’s actual words reveals the civil rights leader saw such moderation as a “fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity.”

From a Birmingham jail cell, he wrote he was “gravely disappointed with the white moderate” that he saw as “the Negro’s great stumbling block,” as much or more so than ardent segregationists or even the KKK. The white moderate, he observed, lived “by a mythical concept of time” and constantly advised “the Negro to wait for a ‘more convenient season.’ Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

As King saw it, the American embrace of moderation in his time was enabled by a belief “that American society is essentially hospitable to fair play and to steady growth toward a middle-class Utopia embodying racial harmony. But unfortunately, this is a fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity.”

In grade school, I was indoctrinated with this same moderate narrative — that we were on the conveyor belt of socio-economic progress that was a through line from Lexington and Concord, through Gettysburg, and on to the beaches of Normandy.

In this airbrushed history, America expiated its original sin of slavery with the massive bloodletting that was our Civil War. Scroll forward to 2008, and we have elected the first American African American president.

Perhaps too slow, argue the moderates, but progress none the less.

Revisiting reconstruction

But our actually history as it was lived, but too often not remembered, reveals that every civil rights breakthrough is accompanied by reactionary blowback. We saw it after the Civil War, with the abandonment of Reconstruction by a federal government that fell captive to capital interests and its own deeply embedded racist world view.

Scroll forward a century: the same happened in response to the passage of landmark federal civil and voting rights legislation. And as with the murder of Lincoln after the Emancipation Proclamation, the white supremacist terrorist rage murdered Dr. King and so many others.

And similarly, after the two-term presidency of President Obama, the election of Trump was the blowback.

There is a pattern here, one that has been flagged by writers like Michelle Alexander and Ta-Nehisi Coates. In 2020, there can be no excuse for not seeing it.

In the southern states after the Civil War, African Americans’ post-emancipation hopes for freedom were crushed when, as Ta-Nehisi Coates reminds us, Lincoln was assassinated by a white supremacist and replaced in White House with Andrew Johnson, another white supremacist.

It was Johnson, Coates observed, who curtailed “virtually all rights black people enjoyed” which cleared the way for white Southerners to “pillage black labor….. through a century-long campaign of domestic terrorism, and that for most of that history the federal government looked the other way, while state and local governments were complicit.”

Coates continues: “I have spent the past two years somewhat concerned about the effects of national amnesia, largely because I believe that a problem cannot be effectively treated without being effectively diagnosed. I don’t know how you diagnose the problem of racism in America without understanding the actual history.”

Black representation disappeared

As historian Howard Zinn writes in “A People’s History of the United States,” after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment — which prohibited states from denying former slaves their right to vote — there were two African Americans in the U.S. Senate and twenty members of the U.S. House of Representatives.

At the local, county and state level there were 2,000 African American elected to office, including 600 to state legislatures in the south.

“The southern white oligarchy used its economic power to organize the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist groups,” writes Zinn. “Northern politicians began to weigh the vantage of the political support of impoverished blacks-maintained in voting and office only by force [union troops] — against the more stable situation of a South returned to white supremacy, accepting Republican dominance and business legislation. It was only a matter of time before blacks would be reduced once again to conditions not far from slavery.”

This terror campaign included not only 4,000 hangings, but the rape of women, the burning of churches and the razing of entire neighborhoods. In response to this, African Americans moved into America’s booming northern industrial cities by the millions.

The Great Migration spurred a massive increase in the African American communities in northern cities. In just ten years, between 1910 and 1920, New York’s black population increased by 60 percent, Chicago’s by 148 percent, Philadelphia’s by 500 percent. Detroit spiked 611 percent.

A new kind of poverty

As Spencer Crew, an historian for the National Museum of American History, described it, the change of scenery and easy employment thanks to war time production did not bring prosperity — but a different kind of poverty.

“While job opportunities were readily available in most cities, these jobs were at the lower end of the occupational ladder,” writes Crew. “Northern labor unions generally did not accept Afro-Americans as members and often threatened to strike companies where nonunion workers performed union jobs. Even when Afro-American workers acquired better paying jobs during the war, many of them had to relinquish these jobs once the war ended.”

As a result, African Americans “typically wound up in dirty, backbreaking, unskilled, and low-paying occupations.” “These were the least desirable jobs in most industries, but the ones employers felt best suited their black workers,” Crew notes. “On average, more than eight of every ten Afro-American men worked as unskilled laborers in foundries, in the building trades, in meatpacking companies, on the railroads, or as servants, porters, janitors, cooks, and cleaners.”

And moving from the south to the north meant they fell prey to a scarcity of affordable housing that endures to this day.

“Funneled into certain areas in most northern cities, Afro-Americans have paid nearly twice as much as their white counterparts for equivalent housing,” according to Crew. “With the additional financial burden of having to pay higher prices in neighborhood stores for food, clothing, and other necessities, settling in the North was a mixed experience for many migrants. Though they earned better wages in the North, much of the increased income was offset by higher living expenses.”

In the mid-20th century, American multinationals, encouraged by U.S. tax policy, began to shift manufacturing out of America’s urban core offshore. Thus, the stage was set for the social unrest that would come in the 60s in places like Newark and Detroit. It was in these urban crucibles that the promise of an ascendant civil rights abutted the consequences of generations of poverty and widening income disparity between communities of color and white America.

“Capitalism is fine — it’s black families that are broken”

For the federal policy makers in the 1960s, like David Patrick Moynihan, an assistant secretary of labor under President Johnson, the real problem was not capitalism, which had decimated America’s big cities and exploited an African Americans underclass. Rather, the problem was the very nature of the African American family itself, which was increasingly led by single mothers.

In his 1964 report, “The Negro Family — The Case for National Action,” he conceded the enduring and systemic toll of the “virus” of white supremacy and offered praise for the civil rights movement. Yet, as others have observed, Moynihan blamed the victim for African American poverty. In turn, this would ultimately provide the academic underpinnings for the brand of overpolicing that endures to this day in black neighborhoods.

“In this new period the expectations of the Negro Americans will go beyond civil rights,” the Moynihan report states. “Being Americans, they will now expect that in the near future equal opportunities for them as a group will produce roughly equal results, as compared with other groups. This is not going to happen. Nor will it happen for generations to come unless a new and special effort is made.”

The report continued: “There are two reasons. First, the racist virus in the American blood stream still afflicts us: Negroes will encounter serious personal prejudice for at least another generation. Second, three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment have taken their toll on the Negro people.”

“The thesis of this paper is that these events, in combination, confront the nation with a new kind of problem. Measures that have worked in the past, or would work for most groups in the present, will not work here. A national effort is required that will give a unity of purpose to the many activities of the Federal government in this area, directed to a new kind of national goal: the establishment of a stable Negro family structure.”

To be fair, Moynihan’s report did observe that the Federal minimum wage provided a “basic income for the individual, but an income well below the poverty line for a couple, much less a family with children” and that the “most conspicuous failure of the American social system in the past ten years has been its inadequacy in providing jobs for Negro youth.”

But by zeroing in on the family and society and not flagging the defects in market capitalism that profited off of black poverty, the power structure now had a rationale to take aim at a “pathology of poverty” they had determined afflicted the African American poor.

War on drugs saddles up

As Jeff Guo wrote in the Washington Post, President Johnson’s “War on Poverty” was followed by a “War on Crime” that “would bulk up police forces with federal money and intensify patrols in urban areas.” “This would be the first significant intrusion of the federal government into local law enforcement, and it was the beginning of a long saga of escalating surveillance and control in urban areas,” Guo writes. He notes that President Johnson “liken[ed] the black urban unrest to a domestic Vietnam.”

As recounted in historian Elizabeth Hinton’s book “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime” Johnson sent “military-grade rifles, tanks, riot gear, walkie-talkies, helicopters, and bulletproof vests,” to local police forces who were afraid of civil unrest from young black men that came from families that liberals like Moynihan had determined were defective and if left unaddressed would be dangerous.

And with President Nixon’s so-called War on Drugs, the stage was set for the mass incarceration of African American men — and with it the tragic collateral social consequences.

Black people in chains: it’s just what we do

We have so deeply internalized structural racism that most politicians easily ignore the fact that between 1980 and 2015 the number of people incarcerated increased from 500,000 to over 2.2 million, according to the NAACP. That means that while the U.S. makes up only 5 percent of the planet’s population, we have 21 percent of the prisoners.

Evidently, we are just not that outraged by it. If people are in jail, there’s some justification for it. Right?

That’s how former Mayor Mike Bloomberg can joke through his recent The Late Show with Steven Colbert appearance and blithely explain away as merely “a mistake” his embrace of race-based profiling where the NYPD illegally stopped and frisked hundreds of thousands of young men of color annually for years.

And with hundreds of millions earmarked as new revenue for hungry broadcast media outlets, don’t expect Bloomberg to be pressed on how he plans on making right the tragic consequences from the NYPD’s unconstitutional actions that led to bad arrests, unjust incarcerations, lost jobs and ruined lives.

This Martin Luther King Jr. Day, pay close attention to the white moderates, like Bloomberg and Biden. Ironically, not only do these men fail to grasp the radical nature of his dream, their past actions actually helped defer it.