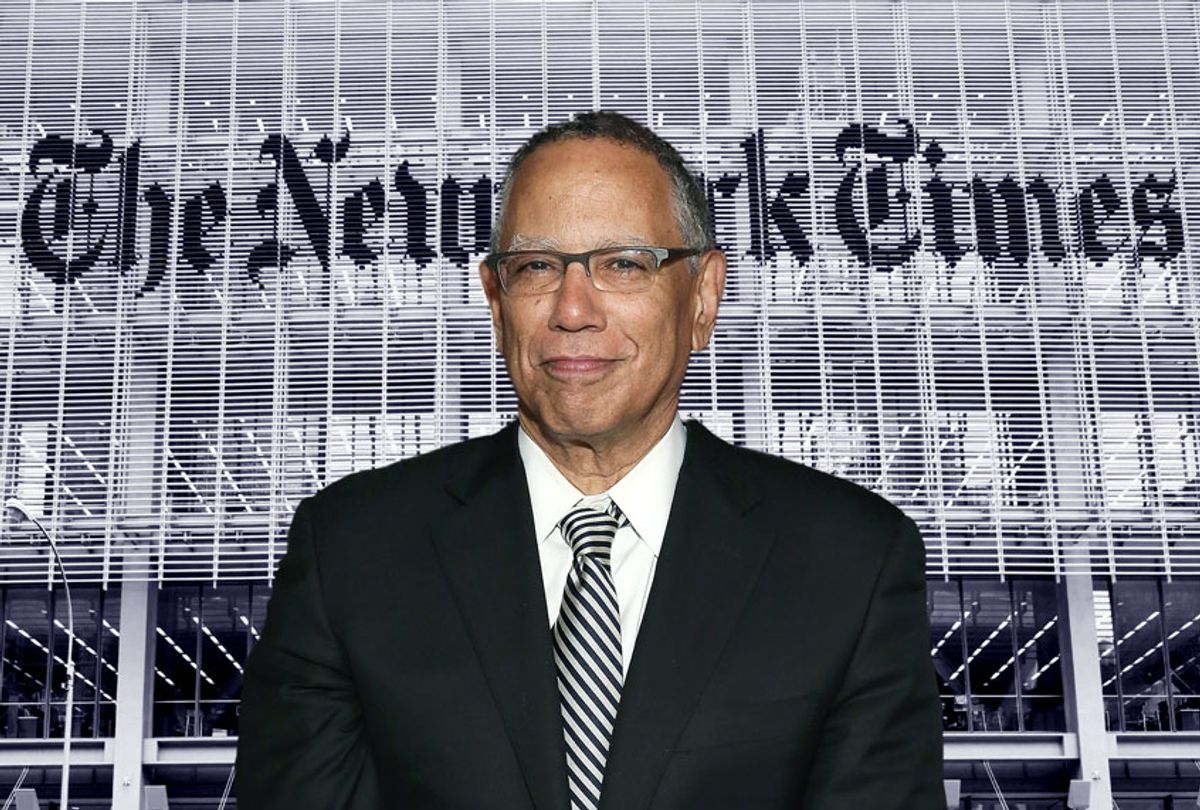

While technically acknowledging that "on the one hand on the other hand" reporting is "not the best way" to cover stories like the Trump impeachment trial, New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet made it clear in a new interview that Times reporters will not be "taking sides" — even when one side is the truth and the other side is a lie – as long as he remains editor.

Talking to Michael Barbaro on the Times podcast "The Daily," Baquet refused to in any way condemn a recent Times article that was widely and appropriately cited as a canonical example of both-sides-ism. The article lamented that "the lawmakers from the two parties could not even agree on the basic set of facts in front of them."

Baquet instead endorsed something he called "sophisticated true objectivity."

"The easy version of what I call 'sophisticated, true objectivity' … is: 'I'm writing my story on deadline. OK. This guy said this, this guy said that, I'm going to gather, you decide,'" he said. "That's not what I mean when I say sophisticated, true objectivity is a goal. True objectivity is you listen, you're empathetic, if you hear stuff you disagree with, but it's factual, and it's worth people hearing, you write about it."

I agree that's a wonderful goal.

But what do you do when what they say is not factual? Do you call it out?

In some cases, you engage in "deep reporting," Baquet said. But you don't do "labeling and cheap analysis." You don't call it a lie, he said.

"Let somebody else call it a lie."

"In my mind, I think of the reader, who just wants to pick up his paper in the morning and know what the hell happened — I'm beholden to that reader, and I feel obligated to tell that reader what happened."

But Baquet's aversion to taking sides means that it's the "easy" version of his "sophisticated" objectivity that has become endemic in his newsroom's political journalism. There are countless examples, but none better than the Dec. 13 story by Michael D. Shear, headlined "The Breach Widens as Congress Nears a Partisan Impeachment."

FiveThirtyEight editor Nate Silver tweeted at the time, "the phrase 'both sides' literally appears 4 times in it." Media critic Jay Rosen tweeted: "Asymmetrical polarization is just too much for the institution as currently led. So they changed it to 50/50 polarization and put it on page one." Author and magazine editor Kurt Andersen tweeted: "It isn't two 'different impeachment realities,' … it's reality and fantasy. Don't let norms of journalistic objectivity become a suicide pact."

I wrote a column titled "New York Times political coverage implodes at the worst possible moment," in which I despaired that capable Times reporters have been corrupted by an editorial regime, led by Baquet, that prevents them from acknowledging elemental truths.

So kudos to Barbaro for directly confronting Baquet with the critiques of both-sides-ism – and that article in particular.

(I transcribed a fair amount of the podcast for those of you who don't have that kind of time.)

Barbaro: When efforts are made to fairly cover this president, his voters, his allies, the Times has sometimes been accused of engaging in what's called both-sides-ism … I'm sure you're familiar with this… this tendency to represent both sides of a debate as equal or both sides as having contributed equally to something. And there was a story a couple weeks ago about the impeachment inquiry that was criticized for this. And I read it very carefully. And among the lines people zeroed in on was this: "Throughout the committee's debate, the lawmakers from the two parties could not even agree on the basic set of facts in front of them."

The criticism was: There can only be one set of facts, so lay them out. Another point in the article it read, "They called each other liars and demagogues and accused each other of being desperate and unfair." The criticism of that is that we can tell who is lying or who is not lying based on the testimony and the evidence that we have. But the story didn't do that. It suggested both sides had legitimate, equal cases. Are stories like that a kind of both-sides-ism abdication?

Baquet: So I'm going to stick my neck out here and I'm going to first offer what I think of as a spirited defense for sophisticated objectivity. I think that we're at a moment where people very much want us to take sides. And I don't think that's the right stance for The New York Times. I do think about the person who picks up his paper in the morning and just wants to know what happened. I do think that we have an obligation to that person, and I do fear that we're sort of — we're pretending that we don't have that obligation.

I do think that American journalism has a tendency to go for the easy version of what I call "sophisticated, true objectivity." And the easy version is: "I'm writing my story on deadline. OK. This guy said this, this guy said that, I'm going to gather, you decide." That's not what I mean when I say sophisticated, true objectivity is a goal. True objectivity is you listen, you're empathetic, if you hear stuff you disagree with, but it's factual, and it's worth people hearing, you write about it.

Does The New York Times, and every news organization, in producing tons of stories on deadline, fall into "On the one hand, on the other hand"? Absolutely. Because, you know, when you cover a trial and when you cover some kinds of stories, that's an OK formula. It's not the best formula for covering Donald Trump and the impeachment trial. And I do think that both-sides-ism — and too easily saying "on the one hand, on the other hand" — is not healthy for the discussion that we're having.

Barbaro: When you talk about people wanting us to pick a side, who are you talking about? Can you explain all that more?

Baquet: Look, I mean, there are different gradations, but many of our readers hate Donald Trump and want us to join the opposition to Donald Trump. Right? Well, I'm not going to do that. And then there are people who disagree, understandably, with what I describe as a sophisticated objectivity. There are people on our staff who disagree with that as a goal. I get that. I really do. That premise of sophisticated objectivity and independence, we should always debate it and question. But I think that that view — that in my mind, I think of the reader, who just wants to pick up his paper in the morning and know what the hell happened — I'm beholden to that reader, and I feel obligated to tell that reader what happened.

I would hazard that people in the Times newsroom are not objecting to the concept of "sophisticated objectivity," but to using it as an excuse for false equivalence. So I think his comment there is pretty despicable.

Anyway, Barbaro did not let up. He cut to the chase.

Barbaro: But where do you draw the line between picking a side and holding truth to power? Because at this point … there's a well-documented pattern of President Trump telling his allies and supporters, denying established facts, spreading misinformation, embracing conspiracy theories. And frankly — this is uncomfortable to say, it was not easy to embrace this reality over time as a reporter, it's against our nature — many of them have a different relationship to the truth than the Democrats and the Democratic Party. Do you think our journalism has sufficiently adjusted to that reality? And how central should that understanding really be to our 2020 coverage?

Baquet: Yeah, I do, actually.

Amazing.

Barbaro: Do you agree with that? As a portion of the pattern? The way the truth is being handled by the two parties?

Baquet: Yes. I think it's less the parties, it's more Donald Trump. I mean, Donald Trump has attacked … well, he's supported by the party … But I think Donald Trump is the extreme version of that. Donald Trump has made it his business to attack all the independent arbiters of fact. And I think that you will find in the pages of the New York Times very powerful reporting that illustrates that. What we haven't done, which some people want us to do, is to say repeatedly, "He's a liar." That's the language, the word. But the reporting, there's no question we've done that.

Baquet's refusal to acknowledging the depth of the schism between the two parties when it come to their relationship with reality is telling, because it's one way of denying the asymmetry that is arguably the most important story of the political moment.

Later, Barbaro asked Baquet again how the Times covers Trump and the Republican Party "repeatedly acting deceptively — some people might call it lying."

Baquet: First off, you report the heck out of what they say and when they say something that's false — I mean, we've done two or three reconstructs of what happened with the U.S. attack on the Iranian general, that shows that some of the descriptions were false — that's reporting. That's not like labeling and cheap analysis. That deep reporting, a lot of reporters. That's my answer to how we cover Donald Trump.

Barbaro: Let somebody else call it a lie.

Baquet: Let somebody else call it a lie. The world today is filled with pundits. The world today is filled with people who can use labels. The world today has very few institutions that can go out and do the reporting independently, powerfully, and that's what I want to do.

The lessons of 2016

This interview was ostensibly about "The Lessons of 2016."

Baquet said that the Times had failed to see what was going on out in the country, and won't make that mistake again.

But he didn't cop to over-covering Hillary Clinton's scandals, or under-covering Trump's.

He expressed almost no remorse for all the horse-race coverage.

And for a guy who talks so much about just reporting what happened, when it suited him he argued that sometimes "you do have to tell people what to think."

That came up when Barbaro asked about the Times story about Bernie Sanders' entry into the presidential race in 2015, which described his candidacy as a "long shot."

Baquet: Yeah, well, let me say two things first. He was a long shot and here, if I can pull back for a second and just talk about journalism. I mean, journalism, by its very nature, is flawed. I want to say flawed, it's also great. It's also for my money, the most beautifully designed way of communication imaginable and there's nothing like it in the world. But there are built-in flaws. The flaws are, you do have to tell people what to think. Most Americans had not heard of Bernie Sanders. Most Americans had heard of Hillary Clinton. And while I acknowledge that we went too far in making her seem inevitable, Bernie Sanders was a guy from a small state, who was a democratic socialist, which is not a perspective that Americans have been known to embrace. I actually think it would have been sort of weird to not pull up and say: This guy's a long shot. I do think we have an obligation, and I think we met it with this story, because we also told you what he stood for — right? — that's the main thing. And you can decide whether you want him to be a long shot. I think we have an obligation to pull back in the moment and say, "Here's our best sussing out of where we think this person stands." And I think that was accurate for Bernie then ….

You know, political reporting, probably more than any other kind of reporting, to be honest, because of the nature of the ups and downs of the horse race, I suspect I would go back at every campaign and re-edit a bunch of stories. But I think we gotta tell the readers in the moment: How should we think about this?

So what has Baquet changed about the Times' political coverage?

Baquet: We've done a whole series of stories from out in the country. We've brought in people from the business staff to go out into the country to talk about the effects of the economy. We're about to announce a plan to put writers in the seven or eight states that we're usually not in. We've added to our regular political staff a religion writer, because I think religion — and, to be frank, abortion — are currents that I don't think we quite had a handle on. And we give huge play now to stories about anxiety in the country. I think if you read the New York Times right now, you read a New York Times that reflects a country that's divided — much more than we understood in 2016.

When it comes to "stories from out in the country," however, the Times has frequently been accused of overcompensating badly with a seemingly endless series of reporters interviewing Trump supporters at diners across Red America, and discovering that against all odds they still support Trump.

Barbaro asked Baquet if he thought maybe the Times had overcorrected:

Baquet: I don't. Not as long as you write about the other perspectives — not as long as you write about, you know, black people who are anxious about Trump and love Joe Biden …. Look, one of the greatest puzzles of 2016 remains a great puzzle: Why did millions and millions of Americans vote for a guy who's such an unusual candidate? Why did people who are very religious vote for a guy who's been married three times, I think? Those puzzles are reporting targets. And I know that every time we go out and we ask people questions about that to try to understand it, people roll their eyes and say, "Why are you going to talk to those people?" Because understanding how those people voted, and how they will vote in the future, is a big and important thing. And to dismiss them as a group of, you know, 35, 40 percent of Americans — that's a helluva thing to dismiss — who should not be in our pages? That's not journalistic to me.

But the problem, as I describe in my article "Political journalists are doing voter interviews all wrong," is not that Times reporters talk to these people. It's that they ask stupid questions that aren't remotely revelatory, the articles all say pretty much the same thing, and they often elide obvious motives, like racism.

As for calling out racism — in Trump or his supporters — Baquet had this to say:

Baquet: There was a big debate in our newsroom and outside our newsroom about whether the New York Times should use the word "racist". And I accept disagreement. My view is the most powerful writing lets the person talk, lets the person say what he has to say, and it is usually so evident that what the person has to say is racist or anti-Semitic that to actually get in the way and say it yourself is less powerful.

I liked what Baquet said about his approach to publishing material that may have been nefariously obtained and released with the intent to manipulate the election.

Baquet: There should not be a whole lot that we learn about important stories that we don't publish. My view is that publishing is journalism; not publishing is political balancing.

Overall, the interview was a clear indication that nothing much will change at the Times until Baquet and other top political editors are replaced with people more willing to stand up for the truth in no uncertain terms

Early in the interview, asked about the Times' failure to see Trump coming, Baquet made clear that he wasn't about to engage in a whole lot of self-criticism.

"If I can say one thing about journalism, though, we do have a tendency to beat ourselves up a little bit too much," he said.

Shares