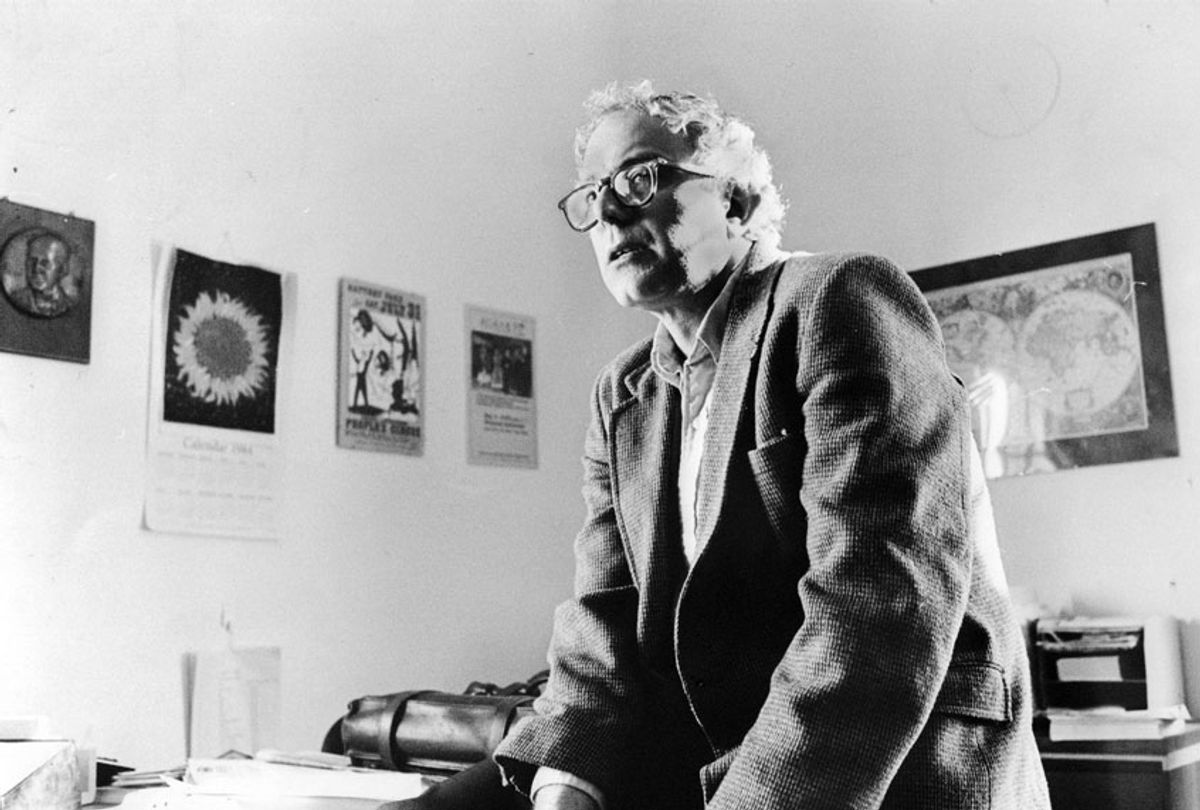

Late last Thursday, I noticed the name "George Wallace" — that nightmarish icon of the 1960s pro-segregation movement, a man so vile he hid his wife's cancer from her so he could exploit her politically — was trending on Twitter. Wallace died more than two decades ago, so I thought was it odd. As Twitter wants you to do, clicked. The situation was wild — people (and likely bots) were making outraged claims that Sen. Bernie Sanders had "praised" Wallace as being "sensitive" in 1972, when Sanders was running for governor of Vermont as an open socialist.

I was immediately skeptical, as Wallace was a notorious villain at the time and Sanders had spent the early '60s helping organize desegregation campaigns. Sure enough, a cursory search showed that the accusation came from the Washington Examiner, a right-wing website owned by conservative billionaire Philip Anschutz.

Of course the full context of the quote soon came out, courtesy of CNN's Andrew Kaczynski: Sanders had said that Wallace "advocates some outrageous approaches to our problems, but at least he is sensitive to what people feel they need." Sanders was not remotely a fan: He compared Wallace to Hitler and argued that Wallace's racism was appealing to his followers who were experiencing "rebellion, frustration, economic instability".

It's a version of the "economic anxiety" argument that often used to explain the rise of Donald Trump. The idea is that racist appeals work on voters who are feeling anxious and looking for a villain, and that if the left did more to ameliorate those anxieties, they could win at least some of those voters over. I think it's a misguided theory: Evidence shows people like racist appeals because they're racist, not because they're "anxious." But its appeal is often innocent enough, since it allows us to believe there's a solution to the often intractable-seeming problem of racism.

Nor was it particularly a controversial idea at the time. Even Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress, made an appeal to Wallace voters when she ran for president, visiting Wallace in the hospital after he was shot and paralyzed in a 1972 assassination attempt.

This whole situation illustrates what Democrats and their supporters need to understand about the 2020 election if there is any hope of beating Trump: Republicans and their allies in right-wing media — and quite likely in Russian intelligence — will attack the Democratic nominee (whoever he or she may be) primarily from the left. Those attacks will look very much like what Sanders just experienced with this Wallace story.

If that sounds confusing, well, it is. The old playbook of conservative politics was more straightforward: Attack the Democratic candidate from the right, with accusations of socialism and insufficient patriotism and none-too-veiled homophobia and class prejudice and racist implications — all with an eye towards winning over swing voters by appealing to their base instincts and mobilizing hardcore conservative voters.

That playbook worked in 2000 against Al Gore, who was characterized as effete for his environmentalism. It worked against John Kerry in 2004, when he subjected to false claims that he hadn't earned his Purple Hearts in Vietnam.

This strategy has stopped working, as increased polarization and the explosion of right-wing media mean that old-fashioned swing voters have all but disappeared, while conservative voters live in a state of permanent mobilization.

Subsequently, the attack-from-the-right playbook failed in 2008 against Barack Obama. Oh, Republicans tried. They attacked the minister at Obama's church, freaked out over Obama's habit of using the "fist bump" gesture, and floated rumors that he hadn't been born in the U.S. — all efforts to appeal to racist fears in white voters. But it didn't work, in no small part because Republicans already had most of the racist voters, and such tactics didn't add to their coalition.

By 2016, however, with the help of Trump's natural instinct for sowing division and the influence of Russian propaganda, another strategy had emerged. Republicans might not be able to add voters to their coalition, but they can subtract voters from the Democratic coalition. The method, then, was to attack the candidate from the left, causing some progressive voters to believe that the candidate was a secret conservative working against their interests and thereby convincing them to sit out the election or waste their votes on third-party candidates.

The explosion of social media has helped a lot, because it can spread rumors far and wide while concealing their origins. For instance, it's clear now that the rumors that Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party had "rigged" the 2016 primary campaign against Sanders stemmed largely from Russian intelligence services, using WikiLeaks as a cut-out to float false accusations based on misinterpreted emails stolen from Democratic officials. These accusations ballooned into a nightmare at the Democratic National Convention, as many Sanders delegates, drunk on outrage over the rumors, booed any mention of Clinton's name at the convention. The controversy helped damage Clinton in a narrow election, by driving angry Sanders voters to vote for Trump, vote third-party or simply stay home on Election Day.

This kind of strategy works by exploiting the fact that few people bother to actually read stories closely, much less track down their origins, before choosing which ones to believe. This is doubly true when the fake story confirms what someone already wants to believe. With Sanders voters, it was easier to believe that Clinton cheated than that she had legitimately won more votes.

Flashing forward to 2020, many of Sanders' critics are suspicious of his commitment to racial justice. So they were primed to believe the Washington Examiner story, especially as the story spread across social media and got detached from its right-wing origins. Things were not improved when knee-jerk Sanders defenders like Elizabeth Bruenig of the New York Times floated the idea that Wallace must have had redeeming characteristics to merit such apparent praise, instead of simply waiting for the clarifying details that showed Sanders had never been an admirer of Wallace.

This little flare-up seems like it's dying down quickly, though who knows whether it will be resurfaced by right-wing sources pretending to be outraged leftists on social media later in the election cycle. But a big problem the Democrats will face in 2020: Republicans will use the chaos of our current media ecosystem to pump lies about the Democratic nominee into the national bloodstream, with an eye towards demobilizing the left and depressing turnout on Election Day.

If it's Sanders, expect more alarming stories about racism and sexism that spread far and wide before they get debunked. If it's Elizabeth Warren, we'll see misleading rumors about her being a Republican, which have been bolstered by trolling headlines from Politico calling her a "diehard conservative" and burying the fact that this refers to her high school days deep in the article. With Joe Biden — well, Trump is already priming the pump with another round of accusations that the primary campaign is being "rigged" in Biden's favor. And there's already a troll army out there spreading rumors that Biden is racist.

We can all do our part to fight back. Check where a story is coming from before you share it on social media. Read articles, not just headlines. Slow your roll on social media, and try to wait for more information to come in. Be wary of trollish outlets like Politico and The Hill, which prioritize sowing discord over telling the full truth. Check Snopes.

Above all else, remember the main rule of skepticism: The more you want to believe it, the more you need to slow down and ask hard questions before sharing.

It's hard. God knows I've screwed up on this front, more than I'd like to admit. But the alternative is electing Trump to another term, so keep that in mind before giving into that temptation to share a juicy story about a Democratic candidate's supposed Judas-like betrayal of all that is good and decent.

Shares