The recent global spread of a deadly coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has led world leaders to invoke an ancient tradition to control the spread of illness: quarantine.

The practice is first recorded in the Old Testament where several verses mandate isolation for those with leprosy. Ancient civilizations relied on isolating the sick, well before the actual microbial causes of disease were known. In times when treatments for illnesses were rare and public health measures few, physicians and lay leaders, beginning as early as the ancient Greeks, turned to quarantine to contain a scourge.

In January, Chinese authorities attempted to lock down millions of residents of Wuhan and the surrounding area, to try to keep the new coronavirus from spreading outward. The country's neighbors are closing borders, airlines are canceling flights, and nations are advising their citizens against traveling to China, a modern instance of the old impulse to restrict people's movements in order to stop disease transmission.

U.S. authorities are holding travelers returning from China in isolation for two weeks as an effort to halt coronavirus' spread. Always at the center of the policy of quarantine is the tension between individual civil liberties and protection of the public at risk.

Keeping contagion at bay

The meaning of quarantine has evolved from its original definition "as the detention and segregation of subjects suspected to carry a contagious disease."

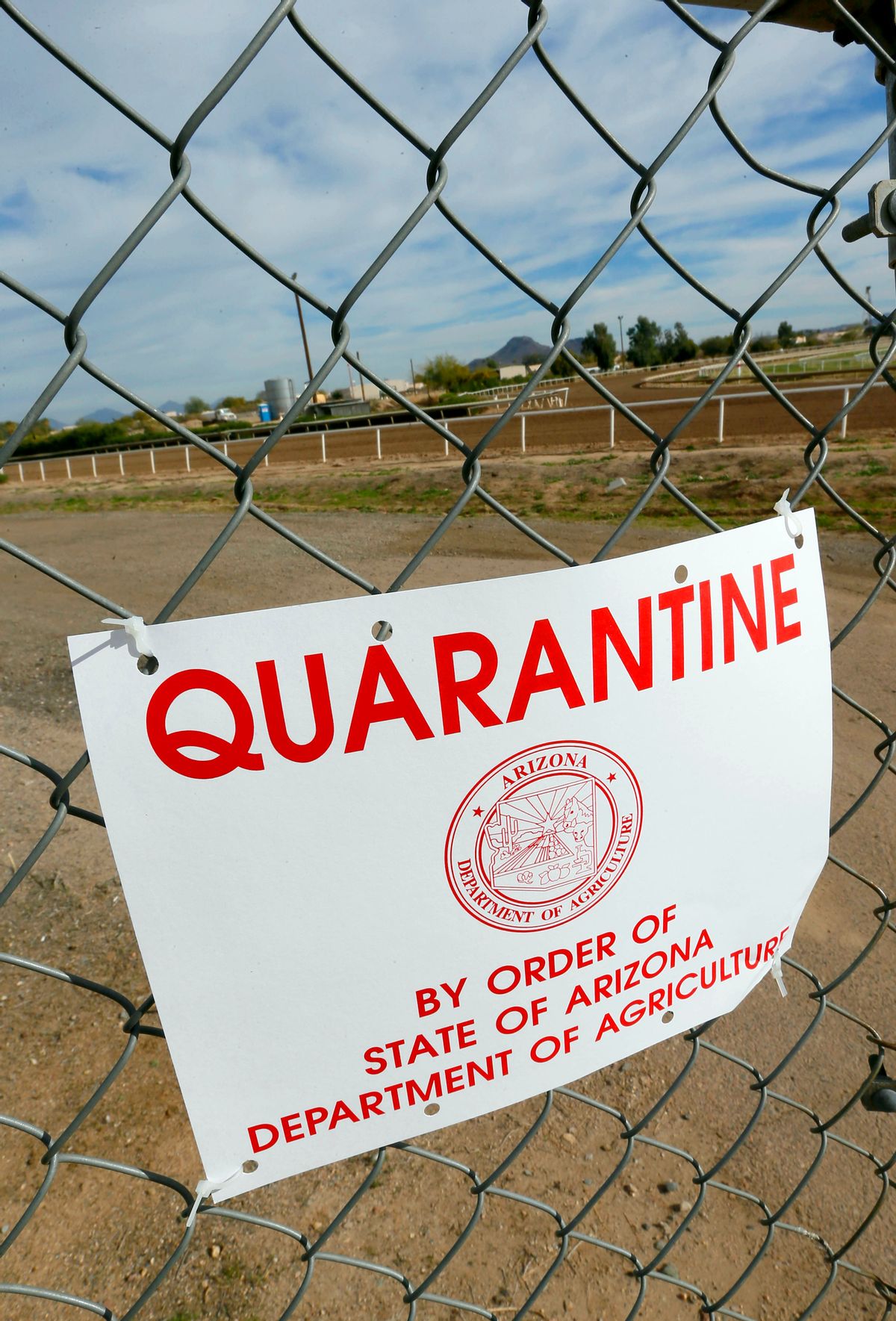

Now it represents a period of isolation for persons or animals with a contagious disease – or who may have been exposed but aren't yet sick. Although in the past it may have been a self-imposed or voluntary separation from society, in more recent times quarantine has come to represent a compulsory action enforced by health authorities.

Leprosy, mentioned in both Old and New testaments, is the first documented disease for which quarantine was imposed. In the Middle Ages, leper colonies, administered by the Catholic Church, sprung up throughout the world. Although the causative agent of leprosy – the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae – was not discovered until 1873, its disfiguring and incurable nature made civilizations wrongly believe it was easily spread.

The plague of the 14th century gave rise to the modern concept of quarantine. The Black Death first appeared in Europe in 1347. Over the course of four years, it would kill between 40 million and 50 million people in Europe and somewhere between 75 million and 200 million worldwide.

In 1377, the seaport in Ragusa, modern day Dubrovnik, issued a "trentina" – derived from the Italian word for 30 (trenta). Ships traveling from areas with high rates of plague were required to stay offshore for 30 days before docking. Anyone onboard who was healthy at the end of the waiting period was presumed unlikely to spread the infection and allowed onshore.

Thirty was eventually extended to 40 days, giving rise to the term quarantine, from the Italian word for 40 (quaranta). It was in Ragusa that the first law to enforce the act of quarantine was implemented.

Over time, variations in the nature and regulation of quarantine emerged. Port officials asked travelers to certify they hadn't been to areas with severe disease outbreaks, before allowing them to enter. In the 19th century, quarantine was abused for political and economic reasons, leading to the call for international conferences to standardize quarantine practices. Cholera epidemics throughout the early 19th century made clear the lack of any uniformity of policy.

Imported to America

The United States has also had its share of epidemics, beginning in 1793, with the outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia. A series of further disease outbreaks led Congress in 1878 to pass laws that mandated involvement of the federal government in quarantine. The arrival of cholera to the United States, in 1892, prompted even greater regulation.

Perhaps the best known example of quarantine in American history, pitting an individual's civil liberties against public protection, is the story of Mary Mallon, aka "Typhoid Mary." An asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever in the early 20th century, she never felt sick but nevertheless spread the disease to families for whom she worked as a cook.

Officials quarantined Mary on North Brother Island in New York City. Released after three years, she promised never to cook for anyone again. Breaking her vow and continuing to spread the disease, she was returned to North Brother Island, where she remained for the remainder of her life in isolation.

More recently, in 2007, public health officials quarantined a 31-year-old Atlanta attorney, Andrew Speaker, who was infected with a drug-resistant form of tuberculosis. His case grabbed international attention when he traveled to Europe, despite knowing he had and could spread this form of TB. Fearing quarantine in Italy, he returned to the United States, where he was apprehended by federal authorities and quarantined at a medical center in Denver, where he also received treatment. Following release, deemed no longer contagious, he was required to report to local health officials five days a week through the end of his treatment.

Quarantine today continues as a public health measure to limit the spread of contagious disease, including not just coronavirus, but Ebola, flu and SARS.

Its stigma has largely been removed by emphasizing not only the benefits of quarantine to society, by removing contagious individuals from the general population, but also the benefit of treatment to those who are ill.

In the United States, where the Constitution guarantees personal rights, it's a serious decision to restrict an individual's freedom of travel and compel medical treatment. And quarantine is not an ironclad way to prevent the spread of disease. But it can be a useful tool for public health officials working to stop the spread of a contagious disease.

Leslie S. Leighton, Visiting Lecturer of History, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares