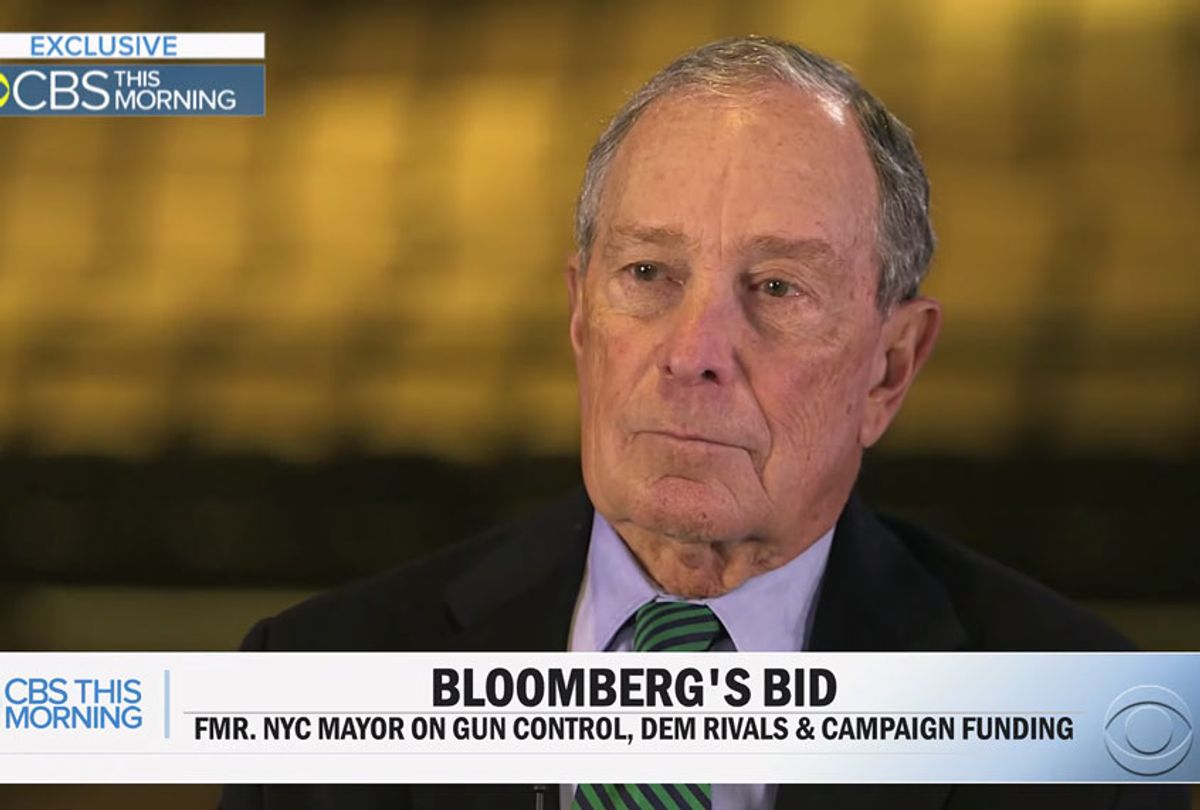

Last night tens of millions of Americans watching the 54th Super Bowl got a preview of what it would be like if our major party Presidential choices turn out to be President Donald Trump and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, one of the richest men in the world.

Both billionaires spent $10 million each to air national commercials, a first for any Presidential campaign. The ads were radically different in tone and substance and presage what an around the clock dueling campaign ad barrage would feel like between the two very different men.

Both billionaires have nine-figure war chests and Mr. Bloomberg, who Forbes ranks as the 9th wealthiest man in the world, is reportedly worth $55.5 billion. Forbes estimates that Trump is worth $3.1 billion.

Trump opted to go with two different 30 second ads.

Promises made promises kept

The one headlined "Stronger, Safer, More Prosperous" hyped his on the job performance using cherry-picked economic data points and closes with him promising the "best is yet to come." It features several images of Mr. Trump addressing large crowds including one at a Royal Dutch Shell plant in August near Pittsburgh, at which the Los Angeles Times reported the workers "were coerced into attending… on pain of losing overtime pay for the week."

"It used to be illegal for employers to dragoon their workers into participating in their political activities," the Los Angeles Times reported. "But that ended in 2010, with the Supreme Court's decision in a case known as Citizens United."

It was that decision that extended to corporations the right to make unlimited independent political expenditures as a protected right to free speech protected by the 1st Amendment. It built on the Supreme Court's 1976 Buckley vs. Valeo decision that equated campaign spending with speech.

"A dog in the fight"

The Bloomberg ad took aim at the nation's gun violence epidemic that claims the lives of close to 3,000 American children a year. The ad is narrated by the mother of a 20-year-old high school football standout who lost his life to gun-violence..

"Lives are being lost every day," said the mourning mother, Calandrian Simpson Kemp. "It is a national crisis. I heard Mike Bloomberg speak and he's been in this fight so long. He heard mothers crying, so he started fighting and when I heard Michael was stepping into the ring, I thought now we have a dog in the fight. I know Mike is not afraid of the gun lobby. They are afraid of them."

The massive scale of the money being thrown around on the national stage so early in the primary process seems to dwarf the actual contests where voters will go to the polls to vote or to caucus as they will in Iowa today.

A process that once started as exclusively localized with real voters in Iowa and New Hampshire, is now becoming increasingly nationalized where the scale of the spending is in the and millions eclipses the actual process of people voting.

Always on turf of his choosing

In fact, Bloomberg's strategy called for him to opt out of these initial local contests where he might be exposed to the perils of the potential awkwardness that comes with that kind of intensive, almost around the clock retail campaigning in one state.

Bloomberg's already running a national campaign and like Trump can pick and choose where he touches down and what he wants to highlight on any given day, anywhere in the country.

Bloomberg stops usually include being endorsed by a local Mayor that he's worked with on his Mayors Against Illegal Guns or with his Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy.

Meanwhile, on planet Earth, the candidates who couldn't afford the $10 million ante for the Super Bowl, are hamstrung by their relatively limited treasuries and the discipline of the primary calendar.

Experts predict that the 2020 election spending to shatter previous spending records. Media industry estimates that spending on political ads could hit $10 billion, a huge spike from the $6.3 billion on 2016.

Has Trump now set the standard?

As divergent as Bloomberg and Trump are on the issues, they both appear to have a flaw when it comes to the disclosure of what they pay in taxes.

Since he announced in 2015, Trump has famously resisted complying with the modern era practice of major party presidential candidates disclosing their taxes to this day.

He did comply with the Federal Election Commission legal requirement for financial disclosure which gives the public a rough sense of his holdings.

For his part, Politico reported Bloomberg has applied for an extension for when he has to file the mandatory FEC disclosure forms until after March "more than halfway through the delegate race and after Super Tuesday, when Bloomberg hopes to make his first splash in delegate-rich states like California and Texas."

As far as his taxes, as I have reported in this space before, all through his 12 years in office as Mayor he refused to disclose his Federal taxes because he said it would provide an unfair advantage to his business competitors.

Politico reports no date for their release has been given.

Back when he was Mayor, Bloomberg saw himself as the champion of Wall Street, to which he himself, and he reasoned the City of New York owed so much. Indeed, he parlayed the $10 million golden parachute he got when he was fired by the brokerage firm Salomon Brothers into a multi-billion-dollar information system business that grew exponentially as Wall Street developed increasingly more complex and riskier financial instruments that helped drive the world to the brink of financial disaster in 2008.

Bloomberg, ever a defender of his friends on Wall Street, publicly pushed back on President Obama's efforts at reforming Wall Street as over reach that would hurt New York City's economy.

"Before I take questions, let me start out by saying how glad we are that President Obama came to New York City to make his case for financial reform," Bloomberg told reporters in April of 2010.

Bloomberg predicted that if the reforms limited the size of U.S. banks, the finance sector would flee off-shore to seek out less strict regulations — taking their business, jobs, and tax revenue with them.

"My concern is for the police officers, fire fighters, teachers and sanitation workers and anyone else who lives in our neighborhoods, shops on our main streets, and keeps our city strong," Bloomberg said. "They get paid by the taxes the financial industry generates."

He called for an open exchange for the sale of derivatives and said he agreed with the president that increased market transparency is critical.

"For me, transparency is not just something I support, I have lived it. I spent part of my first career at Salomon Brothers and all of my second career as an entrepreneur finding ways to build transparency of information and markets," the mayor said.

It's a global world-get over it

But when it was time for reporters' questions, the topic turned to the transparency of the Bloomberg's charitable foundation, which invested hundreds of millions of dollars in legal but controversial off-shore tax havens, like the Cayman Islands.

Sara Kugler of The Associated Press asked Bloomberg to reconcile his call to keep the financial sector within the United States to employ people and pay taxes here with the global investment strategy of his philanthropy.

The exchange grew testy.

"–I don't have anything to say about my investments," Bloomberg said.

"You signed those tax forms, so you had to…," Kugler continued.

"I did not sign those tax forms," Bloomberg said.

"Well, that's your signature on it," Kugler pressed.

"If they're tax forms that I signed, I signed," Bloomberg said. "But I don't have any control over where my investments go. And incidentally, as far as I know the investments that my money managers make are perfectly legal. There're fully disclosed and they're appropriate to maximize the assets which I'm giving away to charities."

"We live in a global world," he added,

In 2012, when I asked him about the structure of Bloomberg LP, which at the time included Cayman and Bermuda subsidiaries, he insisted it was not a tax avoidance strategy.

"We don't leave money overseas," he said. "A lot of that I think is done, and I am not an expert on it, but companies do it, they make money overseas and they don't repatriate it. In our case, other than operating capital all our money is made in sixty-eight countries, but it is all brought back here. It has nothing to do with our business."

Accountability for wealth beyond borders

What is clear is that the growth of great wealth like Bloomberg's has come at a time when globalization appears to have facilitated the amassing of these fortunes in a way that has countries in a race to the bottom in hopes of attracting a piece of the action.

While people get hung up by borders, even made refugees by them, great wealth is its own passport.

"Last year 26 people owned the same [amount of wealth] as the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of humanity," reported Oxfam International in 2018. According to the anti-poverty charity, in the decade since Wall Street's pillaging of Main Street that induced the Great Recession, "the fortunes of the richest have risen dramatically" with the number of billionaires doubling.

Yet, there is an increasing awareness that the structural means by which massive wealth like Bloomberg's and Trump's is legally accumulated — via the U.S. and the world's system of taxation — is what's driving the acceleration of income disparity and wealth concentration both here and around the world. In other words, you can't have one (massive wealth) without the other (increasing poverty and inequality).

We know here in the U.S. that the share of what corporations pay in federal income tax has dropped dramatically, with the biggest multi-nationals like Amazon paying zero. "The corporate share of Federal tax revenues dropped by two-thirds in 60 years from 32 percent in 1952 to 10 percent by 2013," according to Americans for Tax Fairness, a non-profit advocacy group.

Recently the DNC decided it was going to rejigger its rules mid-primary process for participating in the debates by eliminating the requirements for attracting a certain number of donors, making it easier for Bloomberg, who is self-funding, to qualify, assuming he hit the new polling thresholds.

Perhaps the time has come for the DNC to add another requirement, that all the candidates release their taxes.

If Bloomberg really wants to distinguish himself from Trump that would be the most effective way to do it.

Shares