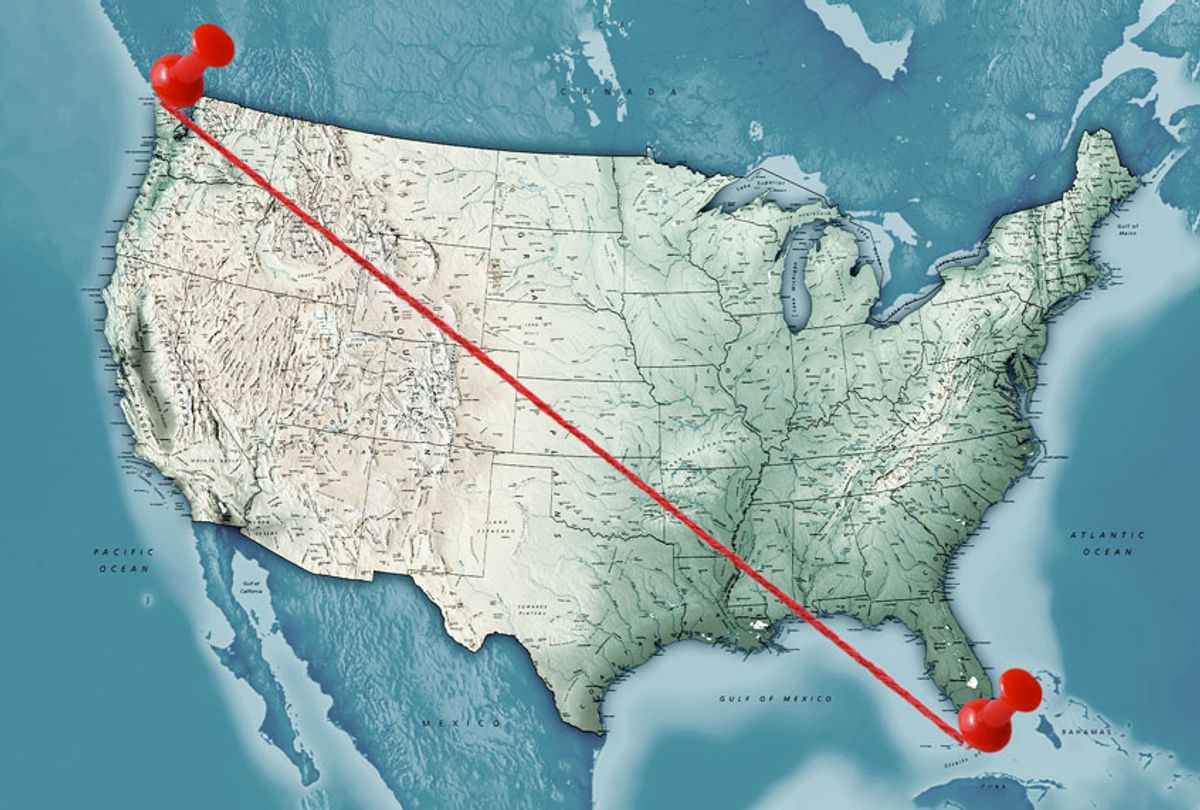

In his mid-'60s, my father unfolded a United States road atlas, laid a ruler across it, and drew a straight line from Cape Flattery, Washington to Key West, Florida. "It's downhill all the way!" he boomed. Then he drove that line, from the northwest corner of the continental United States to its southeastern endpoint—alone.

"I made a rule for myself," my father told me later. "No going beyond fifty miles either side of that line." He recorded notes on a hand-held recorder, documenting his own thoughts and conversations with people he met. Smack in the middle of the country, in a cornfield in Nebraska, he found a chunk of cottonwood and buried it where he could find it again.

"That's for when I go the other way," he said proudly. "Next year I'll go again— from Maine to California!" I'm calling it 'America on the Diagonal.' I'm going to make an X across the country." And he did.

My father's cross-country road trips were pure joy for him. He had traveled on business to places like Thailand, Slovakia, and the Cayman Islands. But in the American small towns, honky-tonk bars, river boatmen, and drive-in movie theaters that he encountered along the way he saw parts of himself.

A decade after those drives, though, my father embarked on an even more impressive journey, one for which he had no map or compass. At 75, still a strong man, he was having trouble with night sweats and a flu-like cold. It was not like my father to be sick. When he was given a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, we never doubted he could lick it. Even at 75, his immense power— 6-foot-4, with a will of iron—always made me think of Mt. Rainier, the highest peak in his home state of Washington, one of many he'd scaled in his 30's.

Dad and I sat in the oncologist's office and discussed treatment. The doctor shuffled his papers impatiently and told us that with chemotherapy the odds were quite high for a continuing to live a "quality life."

But Dad had some concerns. "Several of my friends have really suffered with chemotherapy," he said. "I've seen them in worse shape from the medicine than from the cancer. What would happen if I didn't do the treatment?"

This was 2003 and the doctor looked at my father as if he'd just spit up a hairball.

"You would die," he said. "My job is to keep you alive; this is the only smart choice."

"But has anyone actually chosen not to take this course?" My father folded his large hands in his lap. The doctor paused in dismay, then shook his head. "No," he said, closing dad's file and ushering us out the door.

After a month of treatment, though, Dad contracted an infection and had to be hospitalized. When I visited him at the huge Seattle medical center, he lay flat on the bed, the flimsy bedclothes barely covering his commanding frame. My father fumbled with the straw in his water glass and groaned when he was asked by a nurse to turn over.

Dad's infection soon turned into pneumonia. High fever made him slightly delirious, and he claimed to see people we didn't see. He gasped with pain every time he tried to roll over. To make things worse, his room was regularly shaken by banging on the hospital floor below, where workers were renovating the ICU. The ear-splitting sound of jackhammers and the crash of crumbling plasterboard accompanied the flurry of nurses who scurried in and out with thermometers and pills. I made a fuss about the noise, but a nurse said, "We don't have any control over it!"

"This is exactly what I did not want to happen," my father uttered from his damp, rumpled sheets. He waved his hand at the tray of pale chicken soup made even less appealing under the fluorescent lights. "Do I want this to be my life?"

The next morning, my brother called from Dad's bedside. I had just returned from the hospital late the night before. "You have to come right away," Paul said. "Dad says he has something important to tell us." He wouldn't tell Paul or my sister Rosemary until I got there. So I turned around and drove the three hours back to Seattle, including a ferry crossing. When I arrived my father was radiant, sitting up in bed and smiling, his powerful forearms taut. His hands gripped the handrail. Dad shooed the nurses out and swung his legs over the edge of the bed so he could sit up and command the room.

"I've made a decision," he said. We leaned forward. "I had an epiphany in the night," he closed his eyes. "I was awake, sick of the noise going on below and the madness of this hospital. But then I heard singing." Hallucinations? But his story had none of the feverishness of the previous night.

"I looked up," my father raised his hand. "And the night nurse – her name is Kristy –was singing a spiritual." Dad paused and took a breath. "I said to her, 'Could you sing that louder?' She told me she'd love to and closed the door." Dad looked up at the ceiling. His eyes filled with tears.

"She began singing 'Amazing Grace.' The sound filled the room." My father stretched his arms out to his sides, his hospital gown draping off his strong shoulder like a Roman soldier's tunic. His eyes glowed not only with tears, but with a clarity we had not seen in months.

"Right then," I felt as if I were being freed." He took another long breath. "I realized – he paused, his ice blue eyes bright – "I don't have to do this! I don't have to have chemo anymore or do this awful hospital!" We all flinched as a jackhammer's frenzy vibrated up through the floor.

A nurse burst into the room. "Mr. Hemp! It's time for your shot!"

My father turned to her politely. "I'm not taking any more medicine. I am having a family meeting. Please let us be alone, if you will."

The nurse stopped short and backed up. "But this is the right time for…"

My father held up his large hand, palm toward the nurse. "I said that was it. Thank you. Please leave us alone now."

Against the advice of protesting nurses and without even telling his oncologist, my father was unplugging himself, demanding that he be released not only from the madness of hospital life, but from life as we know it. It felt like a victory.

"Are you afraid to die?" I asked him later. He shook his head. "No! I sent three children to college, I climbed some mountains, I saw a lot of places on the earth, and had a wonderful marriage and family. I think I've done everything I've wanted to do in this life."

His resolve created new strength in me, as if I were part of a winning plan. No jackhammers, no unfriendly nurses, no doctors talking down to us.

That afternoon, another oncologist, a woman in her early forties, came in (Dad's oncologist was out of town). She said she'd heard from the nurse that Dad wanted to leave the hospital.

"But, Mr. Hemp, do you realize what this means?"

"My daughter Rosemary has already arranged for hospice."

"But you can't just leave without your physician's approval."

"I most certainly can," my father said, the tubes dangling free of his arms. "I am leaving today. But tell me, Doctor, what will happen to me? How will it end?"

She explained that his lungs would slowly fill with liquid because of the pneumonia and it would become harder to breathe, until he could no longer do so on his own.

"Thank you so much. I appreciate your honesty. I'll get ready to go now."

She shook her head. "Mr. Hemp, I've never been forced to let a patient take this route before. Ever. It's a pleasure to meet you." She reached out her hand and my father held it tight.

After the doctor left, Dad said, "Guess who wrote this? No, it's not John Keats. He cleared his throat:

If I were to die tomorrow night

And I thought there were things I never might

Be able to do again.

I'd take myself down to the sea

Where the wind and the waves crash endlessly

And seagulls laugh at men.

"Dad," I said, "That's terrific. Who wrote it?"

"Me! Circa 1947." He lay back down in bed and closed his eyes. "Okay, I need to rest now."

The Hospice house — which my father called "The Hyatt Regency" — was filled with caregivers who offered him milkshakes and massaged his hands. "A lot different from that hospital!" Dad announced, smiling.

Our family always went as a group to the airport to pick up whoever was coming home from Boston, London, or Lagos. But we'd decided years before not to belabor farewells, so the departing traveler would head to the airport by shuttle. "No sad goodbyes!" my father would boom from the park 'n' ride.

This time was different. We'd see Dad to the gate.

"Dad is it hard having us all here?" I asked when we were alone. The martini he'd asked for sat on the dinner tray untouched.

"Are you kidding?!" Dad said. "This is the best three days of dying I've ever had!"

That night, I stayed the night with Dad in the fold-out sofa in his room. As he slept, his breath was labored and deep. Often he'd reach up above his head for something I could not see.

At one point, when Dad groggily awoke, he thanked me for looking after him and asked how I learned to do it.

"What? To do what?

"Taking such good care of me. Where did you learn that?"

"Well, I learned it from you, Dad. You always took such good care of me."

"I always will," he said and closed his eyes.

When my father woke again, he said, "Check, please!" and waved his hand toward an invisible waiter. I gave him the nearest thing I could find, one of the many cards sent from friends. I found a pen and Dad scribbled a bit on the card and then passed it to me, exhausted. "Will you sign it, Christine?" I did.

Not long before dawn, my father began speaking of airplanes, flight plans. At one point he asked me if he had his passport.

"Yes, Dad," I said gently. "You have it. No problem." I smoothed the coverlet across his chest.

"But what about you?" His voice carried the urgency of the one in charge of travel plans. "How will you get there?"

"Don't worry, Dad," I reassured him, stroking his solid forearm, "I have my passport, too. I'll be there. I promise. I'll just be on a later flight."

Shares