It’s hardly surprising that if a Democrat wins the White House, taxes on wealthy Americans and corporations will probably go up. How they’ll go up is the more interesting question.

The 2020 Democratic presidential candidates generally agree the U.S. economy faces a variety of challenges: record-high income inequality, decaying infrastructure, failing public schools, climate change that is already leading to fires and floods and a lack of health insurance for millions of Americans, to name a few.

To remedy these problems, every candidate has proposed raising government revenue by increasing taxes on the rich in one way or another, whether through higher income tax rates, a wealth tax or changing how investment income is treated.

Here is a brief look at the tax plans of the top eight candidates in the polls – all of whom will be in the Feb. 7 Democratic debate except billionaire Michael Bloomberg – and what economists like me think about them.

Individual income taxes

President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax reform law reduced the top individual income tax rate from 39.6% to 37%. Every Democratic candidate running to replace Trump agrees that it should be raised. Most suggest returning it to 39.6%; a few think it should go higher.

Bloomberg proposes an additional 5% surcharge on income above US$5 million, yielding a 44.6% rate, while Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders wants a top rate of 52%.

For taxes on lower- and middle-income Americans, the candidates generally say they plan to leave the current rates in place or lower them.

The candidates focus on taxing the wealthy because they say the richest Americans have benefited greatly from U.S. tax policy in the recent past and are no longer paying their fair share.

The question that economists ask when assessing such policies is when do high tax rates have negative economic consequences, such as by discouraging productive work because Uncle Sam takes such a big chunk of each extra dollar they earn.

The standard economic argument for lower marginal tax rates is that it provides incentives for people to work hard and be productive. But it’s not clear at what rate that happens, and 37% does not seem to be the tipping point.

For perspective, every year from 1940 to 1980, the top marginal tax rate was at least 70%. Yet productivity growth and economic growth were both robust over this period.

Investment income

A related issue is should investment income, such as dividends, capital gains and carried interest, be taxed at a lower rate than labor income.

Currently, investment income is taxed at a top rate of 20% – as opposed to the 37% tax on labor income – with other rate differentials at lower incomes. The Democratic candidates all want to end the practice of taxing investment income at a lower rate than labor income.

I believe there are good reasons to do so, as do many other economists.

Primarily, a lower tax rate incentivizes the wealthy to find ways to convert earnings from labor into capital income to reduce their tax bill. And believe it or not, private equity managers who typically earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year have all their earnings classified as capital income, cutting their tax bill in half.

Corporate income tax

The 2017 Trump tax bill also cut corporate taxes, from 35% to 21%, with proponents arguing it would spur business investment and economic growth.

Several studies, however, found little or no evidence of this impact.

And the 2017 tax bill reduced corporate tax revenues as a share of GDP to 1.1% from the 50-year average of 1.9%, putting a larger proportion of the tax burden on individuals.

This is why all the Democratic candidates propose raising corporate tax rates. Some, such as former Vice President Joe Biden and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, want to raise the rate some, while others, such as Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, would restore the pre-Trump 35% rate.

Similar to the individual tax, finding the optimal corporate tax rate can be tricky.

Generally speaking, changes to corporate taxes have little impact on the U.S. economy, so raising them shouldn’t slow growth.

Higher corporate taxes do, however, reduce stock prices, since corporations will pay more money to the government and less to shareholders as dividends, thereby reducing incentives to own stock shares. This can hurt less wealthy Americans with investments in retirement plans and mutual funds.

A wealth tax

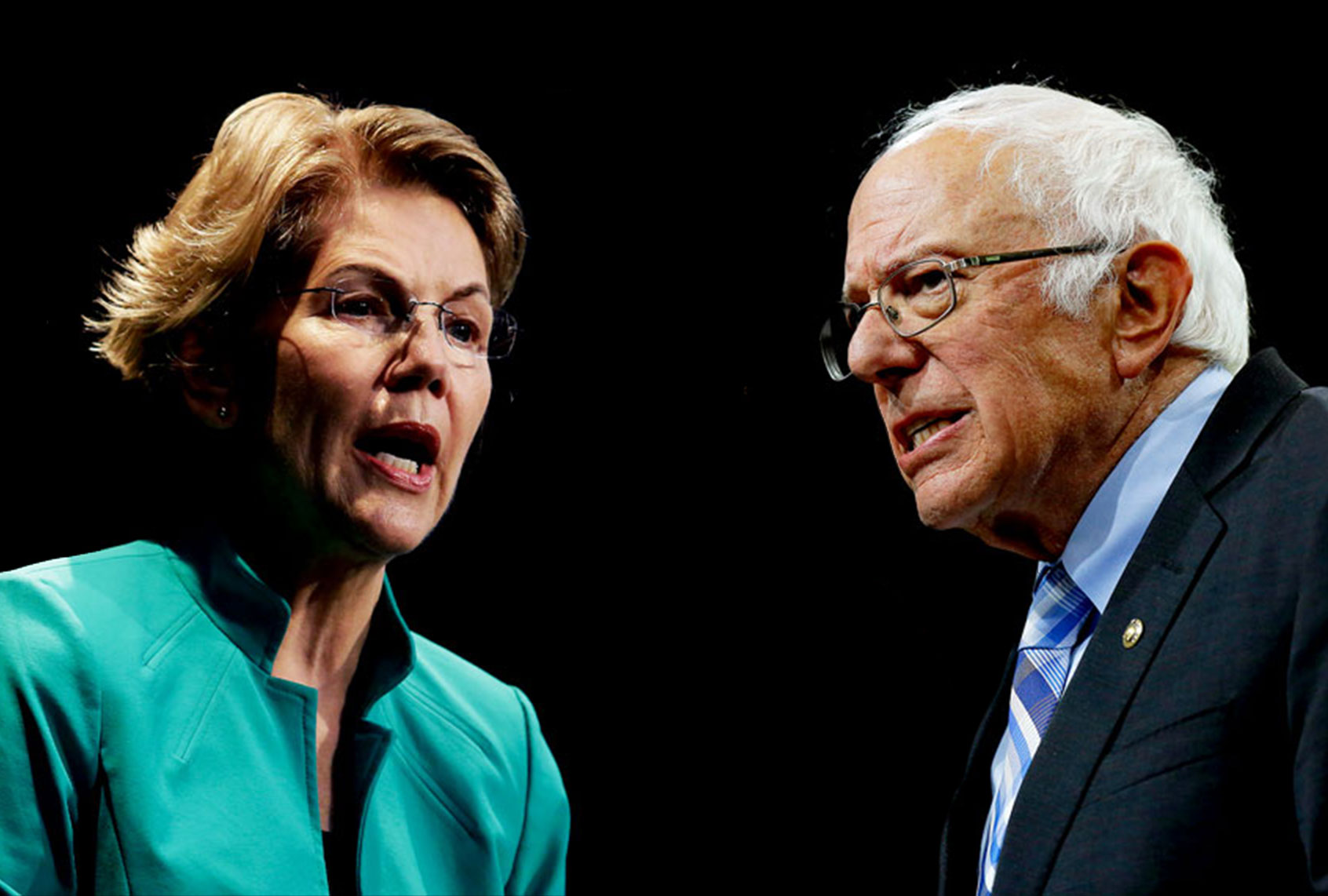

Sens. Sanders and Warren argue the super wealthy should pay even higher taxes to reduce inequality – and to cover their bigger spending plans. Most Americans agree.

Warren wants to slap a 2% tax on net worth in excess of $50 million, and a 3% tax on fortunes in excess of $1 billion.

Sanders would go further. He suggests a tax of 1% on net worth over $32 million that would get progressively higher, rising to 8% on wealth over $10 billion.

Economists are not huge wealth tax fans. They think it would spark tax evasion and, for this reason, not likely lead to much additional revenue.

More than that, a wealth tax may be unconstitutional. Even if Congress were to pass such a tax, it would immediately be challenged in the courts. The Supreme Court would likely hold it unconstitutional, as was the case with the individual income tax, which required the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution be passed before it could be implemented.

Carbon tax

Carbon taxes are taxes on polluting activities, such as the use of gasoline or electricity.

Economists across the political spectrum tend to support taxing carbon because it creates incentives for consumers and businesses to spend money in ways that reduce carbon emissions and slow climate change.

It would, however, increase the cost of driving, flying and heating one’s home. It would also increase the price of all goods transported long distances and whose production requires a good deal of energy. This regressive side to the tax is why Sanders doesn’t support carbon taxes – though most of the other candidates do.

As an example, Yang’s $40 per ton tax would cost the average American family $2,000 a year. Besides helping the environment, the entrepreneur says a carbon tax would help finance his basic income guarantee.

Turning the page

With few exceptions, the Democrats running for president seem to be on the same basic tax policy page.

They all want to raise more revenue by taxing capital income at the same rate as labor income and increasing rates on the wealthy and on corporations. They differ over the extra taxes, like on carbon, wealth and financial transactions.

Whatever combination of these tax changes might be enacted, if a Democrat wins the White House in 2020 and Congress is controlled by the Democrats, the rich will almost certainly lose their large gains under Trump.

Steven Pressman, Professor of Economics, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.