On this year's Oscar night, Brad Pitt won his first acting Academy Award for his role as stuntman Cliff Booth in "Once Upon a Time . . . In Hollywood," Quentin Tarantino's glossy, ultraviolent vision of Los Angeles in 1969. It's a film that culminates in a new interpretation of what happened the notorious August night that a few young members of the Manson family arrived at Cielo Drive looking for actress Sharon Tate. In 1975, another film about an earlier era in Hollywood, a story likewise mired in glamor, sex and murder, was also an Oscar night sweetheart, nominated for 11 awards and winning Best Original Screenplay. The movie was "Chinatown," and its director was Sharon Tate's widower, Roman Polanski.

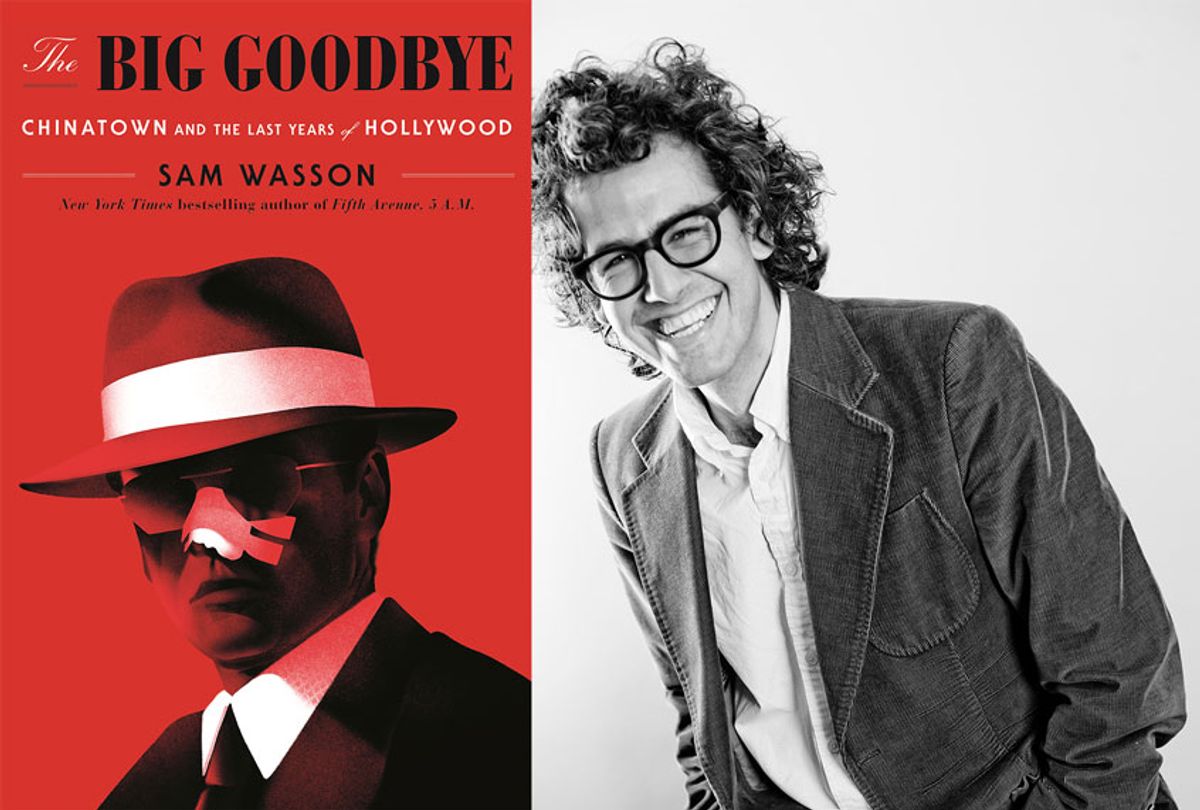

In author Sam Wasson's meticulous new book "The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood," the film historian ("Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M.") turns his eye to the minds behind one of the greatest, bleakest films ever to come out of the studio system. Delving into the lives of screenwriter Robert Towne, producer Robert Evans, star Jack Nicholson and director Polanski, he reveals the inspirations behind the film, as well as the aftershocks it left. And he makes it clear why "Chinatown's" themes of corruption and abuse of power have never seemed more painfully topical.

Salon spoke to Wasson recently about the classic film, why he wanted to write about it right now, and how Chinatown is a state of mind.

One of the films that was a winner on Oscar night rewrites the Tate-LaBianca murders. In real life, Roman Polanski wound up directing a film where he was very clear that it was important to tell a story where things don't work out, where evil wins, where a mother cannot protect her child. Now we have Hollywood celebrating a story that's, "What if that didn't happen?" What does that say about where we are now and the stories we need to tell now?

It's hard for me to understand what that says about where we are now, if it says anything at all. I didn't get it, which isn't to say I liked it or disliked it. I just was confused. It was a pleasure to be surprised. Anytime you're surprised, it's better than a cliche. It was a pleasure to feel something, even if that feeling was wrapped up in confusion.

That crime set in motion a particular chain of events and became part of a moment in Hollywood and the industry looking at itself in a new way. "Chinatown" is obviously part of a cinematic wave that was already in progress, with movies like "Easy Rider," "Bonnie and Clyde," and "The Graduate." But there's this confluence between a real-life event and the insane oligarchy and corruption that was existing in Hollywood. "Chinatown" feels like it came at a moment where that story needed to be told.

It speaks to the American unconscious, and still speaks to the American unconscious. The movie is more relevant now, unquestionably, than it was even then. It was quite literally relevant then, because Roman would go home and he'd watch the Watergate hearings on television and say, "Oh my God, we're making this movie." It was never a conscious project, to make a movie about Watergate and Vietnam and what Robert Towne described as "the futility of good intentions." But it was very conscious of me now, after Trump won, to say, "We are deeper in Chinatown than even Jake Gittes was."

It circles back to this terrible, despairing idea of looking back nostalgically and looking forward, and feeling that there is a cycle of corruption and futility.

Cycle is such an important concept to this movie, and part of what personalizes it to me. The cycle is something we're all in, even on a psychological level. Divorce it from the political, and you get a movie that is about trauma. Chinatown is a stand-in for something that happens in our past that we can't escape from and we are constantly returning to on an emotional level. That cranks up the metaphor into the emotional, and makes it a movie that's so much more powerful than just a political statement.

There's not a moment, watching "Chinatown," that you don't wish that it doesn't turn out differently.

I never think it's going to turn out all right in "Chinatown." That requires a kind of forgetting. The movie is so doom-laden from the first moment that it doesn't let you forget what's coming, especially if you've seen it before. Every image and every sound is inflected with so much sinister feeling. You never really buy the dream.

It's one of the greatest screenplays ever written. Certainly the greatest of of its era. But it was a fight to make it as dark as it was. It was not a foregone conclusion that this story was going to be told in the way that it was told. It certainly doesn't scream, "People are going to love this." Maybe it could only have come out of an era that was already so dark and so painful and so cynical.

I would say we're in a dark and cynical and painful era now, but we do not have the benefit of a Hollywood studio system holding up a mirror to that.

Maybe that's why "Parasite" caught on the way that it did, because it's another film that you don't ever really believe is going to turn out great for these people. That is a film that resonates with such beauty and darkness in a way that "Ford v Ferrari" doesn't.

Yes, but it doesn't come out of our industry and our idiom. That's what I'm bemoaning, not the state of world cinema. There will always be a healthy world cinema as long as there exists a camera and a talented filmmaker. We no longer have a Hollywood to tell us to tell us stories. I do think the country would be a better place if we could use movies to create counter community the way that the Hollywood studios did in the '70s, when counter communities were so desperately needed. Instead we have our counter communities on social media, and they're filled with so much hate and contention that they defeat the purpose of community. Look, we're in Chinatown.

The movie is a perfect example of why we need the movie, because it's given us a metaphor to help organize our thinking about where we are, even though it is not a happy metaphor. It's done better than any movie that Hollywood has made since Trump has been in office to organize our emotions, and to tell us who we are.

Reading the book, I was struck by the deep layers of secrecy in so many of the key players' lives. It all comes together and makes sense then of this film that is about secrets. It's about how corrosive secrets are and how corrosive a misunderstanding of your own narrative is.

Unconscious secrets. Secrets that we don't know that we keep from ourselves.

This film is so relevant right now, because it's about what happens when we are lied to. What happens when we are not given information, even information that may be very painful.

So what can we do? What we can do is do the job of our own self-examination, to make sure we're out of our own Chinatowns. That's really all we can do — and vote obviously. In the personal level, who knows how the vote will turn out? We really can't control that. What we can control ourselves. Gittes' great tragedy is that he didn't have self-knowledge. He should have known better. That's our project in our lives, to know better ourselves. To say, "Oh my God, that's my Chinatown. I can't do that again."

"Chinatown" is such a beautiful way in to a story about this era in Hollywood and these fascinating, complicated, morally unique individuals. Was there something about this particular moment in time that drew you to wanting to write this book right now?

The state of the arts and the state of the government. There are enough people yelling at Washington now for good reason. I didn't need to add my voice to that chorus, although I'm happy to do that. I really wanted to yell at the other Washington, the other Washington being Hollywood, and yell at the art form and at the industry. As if Americans need another thing to get angry about. I'm giving them another, just in case they were starting to feel relaxed. Here's "The Big Goodbye" to ruin your day.

We need to hear it. This ridiculous pushback that Scorsese's gotten, for saying Marvel movies are roller coasters or whatever. That seemed a given, and that was received with such resistance and such animosity. That's what scares me about it. That he was made out to be a curmudgeon or a bad guy or out of touch with reality. Simply for giving what may be the most informed point of view in the industry? I thought, we are in deep trouble. And that it's coming from the left? My people? I'm standing with Marty.

Do you feel moviegoers know what "Chinatown" is? Do you think that this book is going to change that?

In a world where young people don't know "The Godfather," I certainly hope it does. This is a mission to educate. This is my attempt to do that, to educate, to say, "Hey, look at this." This is an art form. And this is what it looks like and feels like when it's in the hands of master filmmaker.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Shares