I wish I could alert you, dear reader, to certain telltale signs that the political candidate you are working for night and day will self-destruct and take you down with them. If I told you to avoid narcissists, then you would have to stay out of politics altogether.

Most, if not all, politicians have massive egos, a burning desire for center stage, and a sense of mission. These men and women want to make history and change the world. Easygoing they aren't.

To be a politician, you need an ironclad ego and a rock-hard belief in yourself and your cause to call up friends and strangers to ask for donations. To wear out shoes going door-to-door canvassing. To sit for endless interviews. To attend tedious cocktail parties and conventions looking for donors with fat wallets. To repeat again and again—literally hundreds of times—your stump speech. And to sound as though you mean every single word of the speech and are uttering it for the very first time.

Perhaps most difficult, politics requires you to expose yourself, and yet more painful, your family, to press scrutiny. That is a big sacrifice. And it is growing larger with every election cycle.

So there's the rub. What makes a politician successful is also what can turn them — sometimes — into entitled narcissists who believe they can get away with things mere mortals cannot.

Politics is a hard business even when you work for someone like Barack Obama, whose administration and postpresidency are utterly free from scandal. And who truly seems like a devoted father and loving husband.

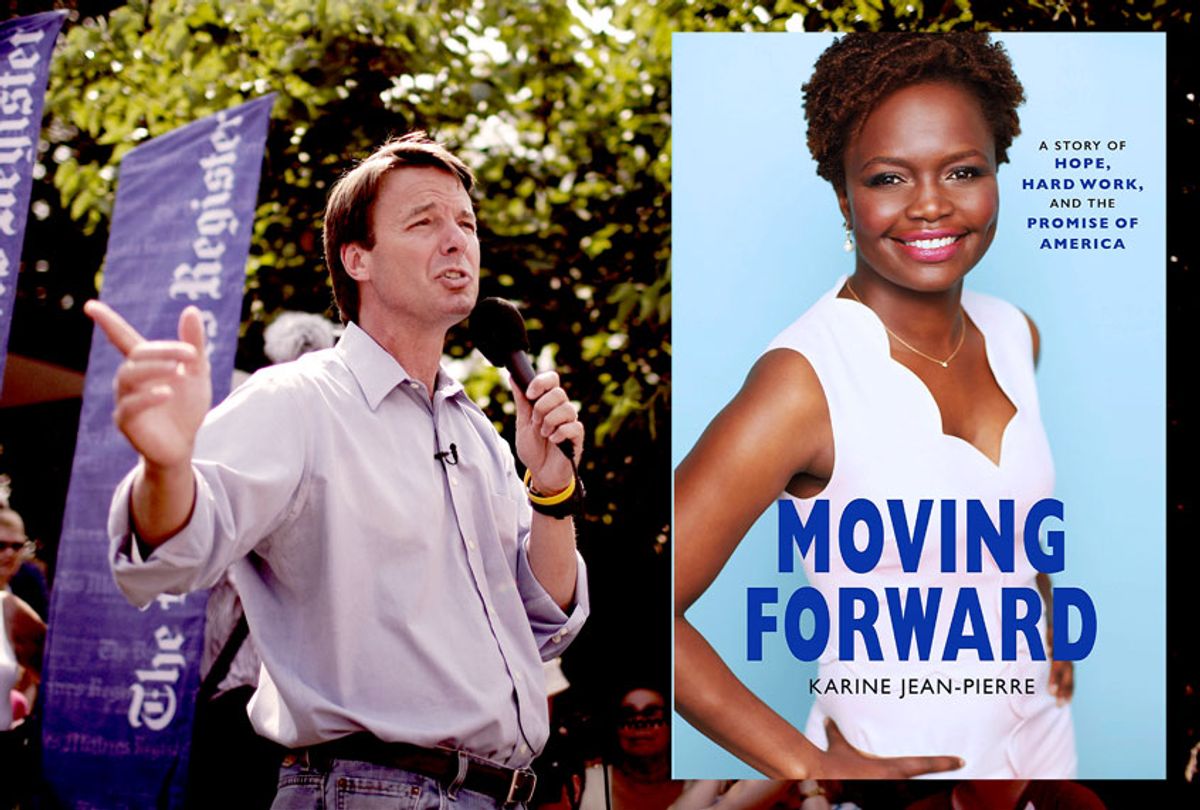

Which brings me to my time working for Senator John Edwards of North Carolina.

In the wake of John Edwards's personal scandal, it's hard to remember that back in the 2000s, he was a charismatic national figure who brought the issue of poverty front and center. Like me, Edwards was the first person in his family to go to college. His father was a mill worker and his mom a mail carrier. Reared in a tiny North Carolina textile town called Robbins, Edwards became an enormously successful and wealthy trial lawyer. After the death of his sixteen-year-old son, Wade, in a car accident, Edwards decided to enter politics and successfully ran for the US Senate in North Carolina. Political pundits called him "[Bill] Clinton without the baggage."

I joined his presidential campaign in February 2007. I had watched the New Orleans kickoff a couple of months earlier and felt inspired. I believed in John Edwards and his commitment to alleviating poverty. Heck, I still believe in Edwards's agenda! When he announced, he said he was committed to fighting climate change, providing universal health care, and withdrawing troops from Iraq.

As a midlevel staffer, I wasn't in constant contact with the candidate. My main job was calling local politicians to find any endorsement I could nab. But, as I wrote in my journal on March 18, 2007, about a meet and greet at Bennett College, a historic black women's college in Greensboro, North Carolina, "I got to meet my boss, the next president, and his wife and kids! Everything just seemed so surreal. It just clicked. This was everything I'd been working for in my life—to be doing that job and standing there in that tiny holding room with JRE [John Reid Edwards] and chatting with his wife. Damn! How did I get there? Unbelievable!"

Did I or any of the other midlevel staffers have any idea that Edwards was conducting a torrid affair with the campaign videographer, a woman named Rielle Hunter? Or that the couple would conceive a daughter and then try to get one of Edwards's closest campaign aides to claim that he, Andrew Young, was the father? And that Young would agree to the pretense. Then Young, along with his own wife and three children, would travel around the country incognito with Rielle. All the while the tabloid publication the National Enquirer would be hot on the trail of Edwards, the Youngs, and Rielle.

But when I was working for Edwards, I didn't know any of this stuff. One thing no one needed to tell me was that Edwards and his message were not connecting with voters. Between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, another white male candidate was as enticing as a bowl of cold grits. The polls showed it, the commentators were noting it, and my gut told me. In no uncertain terms.

Democratic voters like to fall in love with new candidates. So while John Edwards was dazzling and fresh in 2004, by 2008 the buzz was all about the new guy, Senator Barack Obama.

There's nothing more dispiriting than working on a dying campaign. The atmosphere resembles one of those sad birthday balloons with the air slowly seeping out as it deflates. You show up at the office. You're pumped. You attack the phones. You deliberately put pep in your voice. "Everything is going great!" we would blatantly lie to the movers and shakers we were calling. But the more we tried, the less it helped. In the 2008 Democratic primary in the first state where African Americans made up a large part of the electorate, the energy was all about Barack Obama. In South Carolina on January 26, 2008, Obama got 55.4 percent of the vote, Clinton got 26.5 percent, and Edwards got 17.6 percent. Timing is everything, and Edwards's time had come and gone.

Of all my career decisions, the one I most regret is choosing to join the John Edwards campaign in 2007 rather than Barack Obama's. Still, I feel sad about John Edwards. On one hand, I remain grateful that his team gave me a chance to work on a national presidential campaign. And I remain impressed that John Edwards, despite all his failings, really focused the nation's attention on poverty. He was right in 2004 that there are "Two Americas," and it is even more true today. Economic inequality has only grown worse since then. But the whole affair was so squalid. I try not to judge people and their personal decisions involving sex and love, but Edwards was conducting an extramarital affair while his wife was dying. (She would die on December 7, 2010.) That is just plain wrong. He was also running for president and raising enormous amounts of money from donors. Staffers were working their hearts out for him. People really believed in John Edwards.

When Edwards came in third in the all-important 2008 South Carolina Democratic primary, behind Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, I couldn't get out of town fast enough. The tea leaves were clear. John Edwards had been born in Seneca, South Carolina, making him a native son, and had grown up in neighboring North Carolina and served as its US senator. When a "favorite son" gets trounced in his home state and its southern neighbors, it signals that the campaign is DOA.

Back home in New York, I needed work, and Anthony Weiner needed a press secretary. This gig seemed like it had plenty of promise and opportunity. He was a successful congressman who had his eye on running for mayor of New York City but hadn't yet announced.

Yes, I worked for Anthony Weiner.

Yes, that Anthony Weiner.

Carlos Danger himself.

Guess what? Weiner was, hands down, one of the most gifted politicians I have ever encountered. He could read a room instantly. Work the crowd at any parade like a born showman. He was passionate, whip smart, and never at a loss for words. His speeches were effective, and he was a genius with graphic presentations. Anthony Weiner could have been an amazing NYC mayor, US senator from New York, or the governor of the state. The political fairy godmothers bestowed upon him all the gifts. All of the gifts except, well, dare we suggest self-control?

The documentary Weiner captures both his charisma and the collapse of his career because of sexting. It also conveys the manic excitement of working on a high-pressure campaign. There are the scads of fresh-faced, eager volunteers and people seated at phone banks cold-calling voters. It's a good documentary, and I urge folks interested in politics to watch it.

I wasn't burned by my association with Weiner. To be honest, it was just a blip on my résumé. Even a fun nugget to bring up at cocktail parties. Unscathed, I left Weiner's office to go work for the Obama campaign in Chicago, which opened up so many extraordinary avenues. Fortunately, my luck—as well as the luck of the nation—had already turned. I was campaigning my loafers off for a candidate who, as I write these words, still inspires me and fills me with pride.

It is so easy to become jaded in politics and cynical about politicians. You begin to feel dirty just thinking about the endless "dialing for dollars," the trade-offs, the lobbyists, the favor exchanges, the media spin, the quid pro quo. So I end this cautionary tale on "flawed candidates" with this warning: believe in the mission, not the messenger.

You, the volunteer or staffer, should believe in the politician's mission, their goal of changing society, more than in the politician him or herself.

Shares