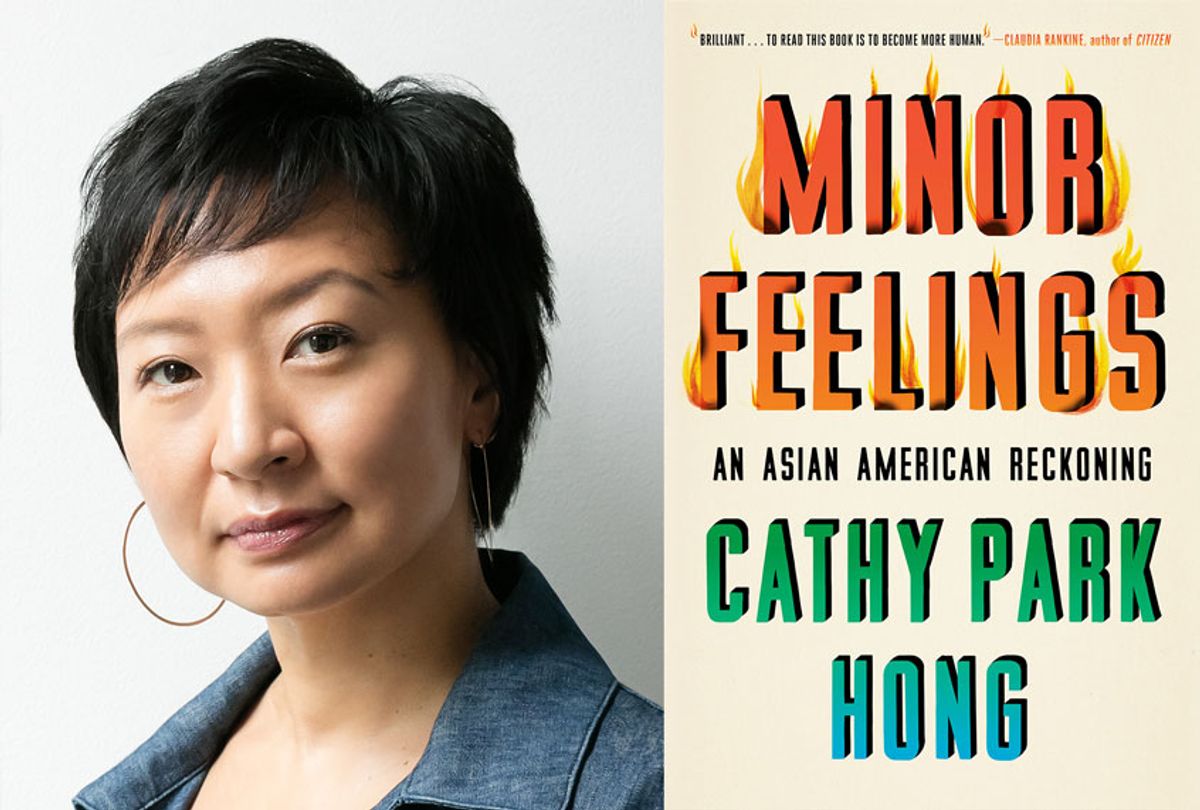

"Minor feelings occur when American optimism is enforced upon you, which contradicts your own racialized reality, thereby creating a static of cognitive dissonance," poet and essayist Cathy Park Hong writes in her book, "Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning."

"Minor Feelings," is Hong's fourth book, and her first work of nonfiction. The book wrestles with Asian American identity, and more than that, the larger topic of race in the United States. Of course, writing about "Asian American identity" is a kind of insurmountable task, given the vast differences in experience across ethnicity, gender, and class, compounded by histories of war and violence, and conditions under which Asians emigrated to the United States. It is further complicated by white America's insistence on seeing "Asian" as a monolith, forever foreign and othered.

What makes Hong's collection so powerful is the way she leans into these variegated truths. In "Minor Feelings," Hong firmly rejects the idea of having the authority to act as a scrivener or "spokesperson" for any racial identity. Instead, she brings together memoiristic personal essay and reflection, historical accounts and modern reporting, and other works of art and writing, in order to amplify a multitude of voices and capture Asian America as a collection of contradictions. She does so with sharp wit and radical transparency.

In recounting and collecting experiences as diverse as her own childhood in Koreatown as the child of immigrants, the history of Japanese Internment, the L.A. Riots, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's rape and murder alongside a study of her classic "Dictee" — among many other historical accounts — Hong undresses themes from shame and indebtedness, to the value of art, to white innocence. Through such contrasting narratives, Hong evokes these candid and uncomfortable "minor feelings," that are considered "overreactions because our lived experiences of structural inequity are not commensurate with their deluded reality," Hong writes her in book.

Salon spoke with Cathy Park Hong about "Minor Feelings."

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you begin writing these essays, and at what point did you know you wanted to publish them as a book?

I wanted it to become a book of essays probably early in 2015, though I didn't have an outline or even an overriding thesis of what this book was going to be. I began writing "An Education," the essay about friendship, and it just grew from there. Originally the book was going to be more focused on institutional racism in the arts. But after Trump got elected, I wanted to broaden the subject of the book and also make it more personal. It became more about my perspective as an Asian American about this country, and about my personal feelings about my racial condition.

I am a poet, and race has always been on my mind — this is not a new subject for me — and I have always been uncomfortable about writing directly addressing Asian American identity. I felt uncomfortable because I wasn't really sure how to address the racial identity that is both very monolithic and flattened by American culture, and also so tenuous and undefinable. And I thought the only way I could do it was to just sit in that discomfort and write through that discomfort. I thought being as self-aware and self-conscious as possible allowed me some integrity in writing about it.

I followed my obsessions. When I was done with one essay, I would think, "Wait, but I'm not finished with this one thread of thought." And that would become the seed of another essay. It happened rather organically within the span of a few years, and none of them were published before. I wanted it to really work as a book.

I think one of the book's major strengths is the way it conveys that impossibility of capturing a monolith. I'm wondering how you chose to weave together such a breadth of themes in your book.

I see the essay as a capacious form and a coalition of many genres. The book is a collection of essays, rather than one memoir with different chapters, or a history book, because I thought the only way I could write about it was through tackling it from as many different angles as possible.

I thought, well, I'll go at it from this angle, from my perspective growing up in Koreatown and then living in a white neighborhood. This angle will be about the rape and murder of the poet and artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and the silence surrounding it. This one will be about my teacher Myung Mi Kim and, of course, "An Education" is about my friendship with these two Asian American women. And this one will be about Richard Pryor — who is not the expected subject on Asian Americans. I was hoping through different anecdotes and historical accounts and philosophical meditations, that people would have an idea of, at least my experience about race.

But I also did not want to prioritize the individual. For me, it was important to write about different perspectives of Asian America — that way I was able to amplify other Asian American voices, other people of color. This book is one perspective, but I'm hoping I also lift up other voices.

This makes me think of your essay "Bad English," where you call the modular essay the right form for your work, because it allows you to "speak nearby" the experience of others.

I think it was really important that I did not claim any kind of authority on the subject. Whenever you write a book like this — and you're writing about the Black experience or the Muslim experience — the audience, especially if it's a white audience, will automatically position you as a spokesperson. It's essential for me to qualify, in essay, that I couldn't speak for anyone. That it was my own perspective on Asian American identity. What I'm trying to do with the book is raise questions, and open up a conversation, so that the conversation about Asian American consciousness will be more liveable, agonistic discourse rather than one monolith replacing another monolith.

At what point did you put a name to the sensation of a "minor feeling"?

I had that lightbulb moment when I was working on the stand-up essay about Richard Pryor. I realized, this is what I'm trying to talk about, it's "minor feelings." I was struggling to write that essay. I could go for a whole day not even being able to write a good sentence, but the beauty of writing — or the torture of writing — is that when you feel like you're wasting time, your brain is still working. There were times where I would wake up at four in the morning and open up my laptop to write down my racing thoughts.

That was when I started thinking, oh yes "minor feelings" is what I'm talking about — that racialized range of emotions that you have because your reality is not acknowledged by dominant culture. And so that stuck.

But I want to emphasize that I am not the inventor of this term, it's really in conversation with so many thinkers. It's in conversation with Sianne Ngai's "Ugly Feelings" and with Claudia Rankine's work. It's also in conversation with the Korean idea of "han," it's just my own set of interpretations of everything that I've been living. The word "minor" also has so many shades of feeling. You could say minor as opposed to major, minor as in minority, minor as in diminutized and unimportant. But underneath that minor is, of course, these very major, roiling emotions that are not legible, that are not being recognized . . . Minor is not just a stand-in for minority! . . . Sometimes you just have to push back – being offended is part of the process.

Now there's a million dollar quote. Anyway, is there anything that didn't make it into the book that you had a hard time cutting?

I don't know if I should say this, but the first essay I actually wrote didn't get into the book. It wasn't even an essay, it was just a really bad draft. And it was about watching pornography while I was pregnant. I don't know, it was about sexuality, which I address a little in the book. But I thought, that's a whole other book. There's just too much I'm already covering in this book, and I don't need it. It was also my first attempt at writing nonfiction for this book, and it just wasn't very well written.

I actually did talk about the essays that didn't make it in the book. In the last essay in the book, I mention the anecdote about the pool. I tried many many times to write an essay about the history of the swimming pool in the US — the racial history of the swimming pool. That didn't work out for reasons I mentioned in the book, which is that the swimming pool was so much about segregation, black white relations. I didn't know how to bring my own experience into that. A lot of the research was not my research, it was what I was getting from other books and articles. I just didn't feel comfortable writing an essay about that.

I had a really difficult time trying to find a final essay for the book. Another essay was trying to imagine what life would be like in 2050, and I was like, I have no idea — I just can't imagine. I'm just imagining "Mad Max: Fury Road." And I thought, maybe I can write about how representation is the future, and the problems with that. But that felt too big and broad. There were others, a lot of half finished essays and ideas that just didn't make it.

The transparency of your writing — your own minor feelings — are part of what makes this collection feel so evocative to me. I wanted to ask if you felt trepidation in publishing, though I'm not sure if this is a reductive question. As I read it I couldn't stop thinking about what my own mom's reaction to sharing this type of information would be, and how it runs counter to "saving face."

It helps if your parents don't understand English, but that was going through my mind. I have a 5-year-old kid myself, and I'm still scared of my parent's reaction to the book. I had to reveal some painful memories, and I definitely felt a lot of trepidation putting it down and publishing it. Not all Asian cultures are like this, but definitely in Korean culture there is the saving face phenomenon where you want to present the best side of yourself, and present nothing vulnerable and negative, otherwise you're bringing shame upon the family. And it is a kind of censorship, I think it censors a lot of the way Asian culture has been presented. You don't see any of the toxicity and also realness of the way Asian families are, and so that was also just really tough, trying to reveal as much as I could.

I just found out there's a Korean publisher that's interested in translating and publishing the book. I don't know if that's a good idea, because that means my parents can understand the book, plus I have no control. My Korean writing skills are terrible. I don't know how good the translation would be. This is a problem I never had to deal with as a poet.

So, will you be doing any stand-up during your book tour? I loved that bit in your Richard Pryor essay, and I told myself if this was going well, I could maybe ask you that.

Oh no, that is a phase that I will never return to. And I think that will be a gift, not only for myself, but for the audience. I will not try to force that on anyone else. Nope, I am not doing that ever again. I think I was in a very weird period of my life where I was feeling very masochistic and I was like, you know what, f**k it — I'm just going to do this and see what happens. I'm over that phase, I'm not returning to it.

"Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning" is on sale now.

Shares