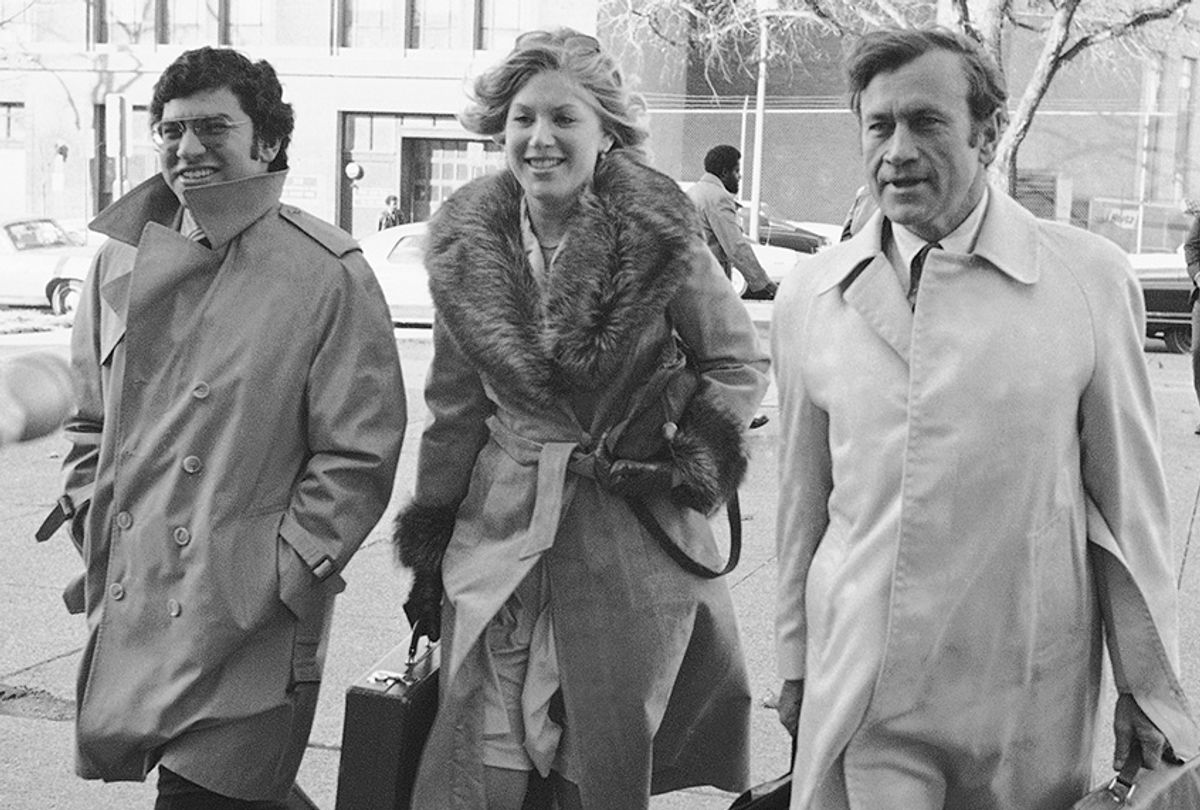

Jill Wine-Banks has seen the Donald Trump story before — at least in a manner of speaking. It played out for her in 1973, when she became the first and only woman serving on the Watergate prosecution team. As she writes in her new book, "The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President," Donald Trump reminds her of Richard Nixon, "corrupt, amoral, vindictive, paranoid, ruthless and narcissistic." But will Trump's story end the way Nixon's did, with him leaving the White House in disgrace?

When I spoke to Wine-Banks on "Salon Talks," the current MSNBC legal analyst shared her improbable story of breaking barrier after barrier. She was the first woman to serve as a staff lawyer in the Department of Justice's crime and labor racketeering section, then became part of the Watergate team and after that she made history when she was tapped by President Jimmy Carter to serve as the first female general counsel for the U.S. Army. But as Wine-Banks explained, she never set out to be a trailblazer. She simply had no choice because women in the legal field — as well as in larger society — had largely been limited to what men in power would allow them to achieve. She refused to accept that.

Wine-Banks told me she believes Nixon should have been indicted for his crimes and criminally prosecuted in 1974. But Leon Jaworski, the special prosecutor in charge of the Watergate investigation, refused to allow his prosecutors to charge a sitting president.(Nixon was later pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, which meant he could not be criminally charged after leaving office.)

There's an interesting open question that Wine-Banks discusses: Had Nixon had gone to prison, would that have deterred Trump from his wrongdoing by making clear that even presidents are not above the law? Regardless of that hypothetical, Wine-Banks is adamant that Trump should be indicted for his criminal activity, from his hush money to Stormy Daniels in violation of federal campaign finance laws to his pressure campaign against Ukraine's president, urging him to investigate Joe and Hunter Biden.

You get the sense that Wine-Banks would love to be part of the prosecution team that may one day prosecute Donald Trump. She told me she believes that "Trump is more dangerous" than Nixon because he does not respect the rule of law and because the Republican Party is defending every action Trump takes. This is an alarming warning coming from a person who saw Nixon's criminality up close. Watch my "Salon Talks" episode with Jill Wine-Banks here, or read a transcript of our conversation below, lightly edited for length and clarity.

This book should be a series. It should be on Netflix. It's got everything. It's got intrigue, it's got affairs, it's got politics. It even unintentionally describes what we're seeing now with Donald Trump, to be frank.

Well, I hope Netflix is listening! Yes, I was at a unique time in history where I was able to be at the crossroads of the woman's movement, be a pioneer.

Let's talk about your fight for gender equality. At the time you were a pioneer, and even the title of your book, "The Watergate Girl" — explain why you have that word in the title.

I will say that it's a publisher's choice, what to call it, but I came to embrace the title because of two things. One, they said, "What were you called back then?" And I had to admit, I was called a girl. I was called a "lady lawyer," as if I were different than other lawyers, which I object to. I don't represent women. I represented the Department of Justice and then in private practice I represented criminals defendants. But I think that captures the era in a way that no other word could. It is what I was. I was the Watergate Girl. There were no other women on the trial team. The only other significant woman was the witness, Rose Mary Woods [Nixon's private secretary], who was actually looked at as a potential defendant for having possibly erased part of a tape that was subpoenaed.

During that time, did you feel an extra sense of responsibility that on some level you represented your gender?

Yes, absolutely. It's sort of like being the older sister. If you do something bad, the younger sister doesn't get to do it and it's the same thing here. My proudest moments are, for example, that I was the first woman to be general counsel of the Army. My successor was a woman and that made me very proud. I didn't screw it up. Somebody said, "Oh, women can do this job." So I think it's important. I didn't, by the way, start out to break barriers. That wasn't my goal. I didn't even become a lawyer to break barriers. I went to law school because when I graduated college, I was a journalism major and the jobs that girls were offered were on the "woman's page" and I wanted to do serious news. I wanted to do foreign affairs or legal stuff. So I thought if I went to law school, I would be taken more seriously by a potential editor hiring me for that. And somehow, somewhere along the line in law school, I decided I had to pay off my law school tuition debts, so being a lawyer for at least a few years would help. Somehow I never left it until now.

You studied journalism, and now you're on TV and you're known for your work on MSNBC as a legal analyst. During the Watergate investigation, you became known for your cross-examination of Rose Mary Woods, who was Nixon's longtime secretary. Everyone knows about the Watergate tapes, but they might not have the details. There's this 18-and-a-half-minute gap during a conversation with Nixon and key people after the Watergate break-in, which became critical. Share a little bit about that.

So first let me say Rose Mary Woods was much more than what a secretary was back then. She was an adviser to the president. She was a friend of the family. She and Pat Nixon exchanged clothes. Her brother, who was Sheriff Joe Woods of Cook County [Illinois], my hometown, exchanged suits with Richard Nixon. She was known as Aunt Rose by the girls. I have recently learned that she was called Uncle Rose by her great nephew and his family.

But going back to her role, she was thrown under the bus by the Nixon White House. When they finally realized they were going to have to turn over the tapes they said, "OK, we'll give them to you." And then they said, "Oh, there are two missing." So we had a hearing in public to find out what had happened. In the first hearing, Rose Mary Woods was a chain-of-custody witness, meaning, she had handled them. We had no suspicion that she had done anything to cause the two tapes to go missing.

She was my witness because I said to my trial partner, Richard Ben-Veniste, "You're taking too many witnesses. I'm taking the next witness and I'm going to share equally after that." She happened to be the next witness called by the White House, so she was my witness. A few weeks later, the White House said, "Oops, there's a third tape missing. It's not missing exactly, but there's an 18 and a half minute gap, just a hum where there should have been conversation. There can be no innocent explanation that we can find and the only one who can talk about it is Rose Mary Woods."

Since she was my witness the first time, I assumed she would be my witness again and just went ahead and prepared for it. In Leon Jaworski's his book, he actually takes credit for saying that she should be my witness. If he did that, I'm unaware of it. I just assumed she would be my witness, but I don't care who takes credit for it. She was my witness when she became basically the chief suspect in an obstruction of justice case. We had a very dramatic time together that ended in the White House because her demonstration in court failed.

She was sitting in the witness box, which is a small thing. On the edge of the witness box was the tape machine that she was listening to, her headphones, a foot pedal which was underneath on the floor, and the machine. In order to work it, she had to keep her foot on the pedal. She said she had her left foot on the pedal and the telephone at the far end of her desk rang. She had her left foot on the pedal and she reached over, keeping her foot on the pedal to get the phone, and talked for, she said, four or five minutes. Well, how do you erase 18 and a half minutes?

Then of course we had a group of experts look at the tapes and there were at least seven to nine separate erasures. It wasn't one continuous, "I made a mistake." It was, "I listened and erased because it was bad. And then I listened some more and erased more and more and more and more and more." It was not an accident. Clearly, it was a deliberate erasure. It did not happen the way she said.

In the courtroom she had the headphones on and I asked her another question and she sort of lifted them up and said, "What?" And I said, "Well, maybe for this demonstration you should take them off. So subsequently, when I'm asking her to please describe each step you took: You pushed the button, that was the mistaken button; instead of stop, you pressed play. What happened next? She said, "Well, I had to take those off to answer the phone." And as she delicately pointed to those headphones, her foot came off the pedal and you could see the tape stop moving. And the courtroom was filled with press. They emptied out to go to a bank of pay phones.

There were no cell phones back then. So they ran out to call the story in and she muttered, "Well, it's different in my office. I did it there." And I said, "Well, then maybe we should adjourn to your office." Nobody objected, and we did. So that was my first visit to the White House, and her office was just down the corridor from the Oval Office.

All the other lawyers went as well?

By that point, the White House was no longer representing her. The White House said, "We can't represent you anymore and you'll have to get your own lawyer. So her lawyer, his son, his son's wife and a friend of hers were there, along with a White House lawyer, the White House photographer, myself and one other person from the special prosecutor's office who had a science degree. It wasn't all that helpful to understanding what was happening with the tape machine.

There was a famous photo taken by the White House photographer, which is in your book. If people search for "Rosemary's stretch," they'll see it everywhere and how she made it impossible for her first story to be credible.

You can see her hand holding onto the chair, with white knuckles, in order to not fall off her chair when she was reaching. I got letters from secretaries around the country saying, "I've used that machine. It's not possible. You can't do it that way. It wouldn't just happen that way." It really did turn the American public against the president and make them really pay attention to the facts, which I wish people would pay attention to now.

It's remarkable: That one cross examination and that photo had a big impact on public opinion. It was one of the building blocks to Nixon being forced out eventually. When you joined the Watergate team, did you think Richard Nixon was personally involved or was that later during your investigation?

First of all, I was raised to respect the president and the presidency, so I didn't start with any negative determinations. But I also was an astute reader of [Bob] Woodward and [Carl] Bernstein, and their reporting made it clear that this burglary was not just a break-in, that it wasn't a random act, that it was something political.

And Judge [John] Sirica's questioning during the trial of the burglars made it clear that he didn't believe that it was a third-rate burglary, as the White House called it, that it was something much more. He kept pressing people. By the time we were appointed in May, one of the burglars had written a letter to the judge on the eve of sentencing saying, "Judge, you're right. There were others involved besides us. People lied in this courtroom when they could have told you the truth. Hush money was paid." That was James McCord and from the moment that was released, I felt pretty clear that there was involvement at the White House, from the Committee to Reelect the President, known as CREEP.

James McCord was a former CIA operative working at CREEP doing security. And Gordon Liddy, who was like the mastermind of this stuff, sent out an employee who they could easily trace back to CREEP.

Yes, and they taped the door [during the burglary]. They taped the door, which is how they got caught, because the guard who does security checks goes, "Oh, why is there tape on here?" That's what led to the discovery of the whole thing. And they had someone watching from the Howard Johnson across the street from the DNC offices in the Watergate, and that person was watching television instead of watching when the police actually pulled up because the guard called the police and he missed it. So he could have averted them getting caught if he had called them in and said, "Get out of there." They had walkie-talkies.

There's an event most people know about if you follow Watergate, called the "Saturday Night Massacre," in October of 1973, when Nixon forced the firing of the special prosecutor at that time, Archibald Cox.

Right. Yes.

You were part of the team. What was it like for you when you heard that the person you were investigating, the president of the United States, had fired the lead investigator? Were you stunned?

First of all, we were young and naive, but we weren't stupid. We knew we were building to a fight with the president because we were insisting on turning over documents and tapes, and he was stonewalling. Archibald Cox called a press conference because our press officer, Jim Doyle, said, "You need to tell the American people why you need the tapes and why you have a right to them." And no one could have been more eloquent than Archibald Cox. His integrity was beyond reproach. His way of presenting it really was convincing, but not to the president, who said, "Too bad, I'm still not doing it. And not only that, but you're fired." He tried to get [Elliot] Richardson, who was the attorney general to fire him. Richardson said no. So he was fired.

Then the deputy attorney general, Bill Ruckelshaus, took over, and he said no. So he was gone. And then the third in command was Solicitor General Robert Bork, and he carried out the order. By that point, I had left Washington for New York. I was at a family wedding, and when I got back to the hotel, the desk clerk ran from behind the desk and said, "You have a message." And he handed me a phone message that said "The FBI has seized our offices, call immediately." So I flew back at 6 a.m. the next morning, on the first flight I could get, and was there for basically everything else that happened.

Again, that was the world before cell phones. Today you'd be texted instantly.

I would have known. But I had no way of knowing. I left right after the press conference. At first I had said I wasn't going, and everybody said, "Are you kidding? What could happen? He'd have to fire Richardson to get rid of Cox. No, nothing's going to happen. Just go. No big deal." So I went. Now, we did anticipate — we had taken copies of documents to our homes.

You were fearful.

We were fearful that Nixon might do something. We didn't think it would really happen. But just in case. We didn't take any originals, but we took copies. We didn't want to have to do this, but we were prepared just in case.

You talk about wanting to indict Richard Nixon at the point where the crimes were clear, and obviously he was not indicted. This is all speculation of course, but do you think that if Richard Nixon had been indicted and prosecuted and gone to jail, it would have been a deterrent for future presidents, and especially Donald Trump, to know that you are not above the law?

I think it is the morally correct thing to do. I think it's the constitutionally correct thing to do. When you have clear evidence, there is nothing in the Constitution that I can see that says the president cannot be indicted. So I think he should have been. I was troubled by how a jury would react to the fact that all the people just under the president are indicted and going to be convicted, and he's not a defendant.

I was afraid that they would have jury nullification, that they would have voted not guilty because it wasn't fair. Obviously that didn't happen. The president was named an unindicted co-conspirator, and we were allowed by the courts and by Jaworski to turn over all the evidence we had to the House Judiciary Committee, which was conducting a credible investigation. They were calling witnesses, they were actually doing impeachment the way impeachment was intended to be done. So we did have an option that doesn't exist today. So I think that indictment is still allowed. We're going to have to rely on state prosecutors because the federal government under William Barr will not allow this to proceed.

When you look at the evidence of Donald Trump's potential criminality, is there enough there to indict him? Do you think he should be indicted?

Yes and yes. Those are the short answers. The evidence from the Mueller report was clear enough, and in fact a large group of Watergate prosecutors — not just my Watergate conspiracy and obstruction of justice trial team, but from the entire office — we wrote an op-ed based on the Mueller report saying there is enough here. Anybody else would be indicted on this fact basis. In the Ukraine case, with absolutely clear violations of law, that's definitely an indictable offense. And let's not forget that his lawyer, Michael Cohen, is in jail for things that he did at the direction of Donald Trump. Clearly that's indictable. He is Individual #1, named in the indictment.

So yes, there are plenty of crimes, and that doesn't even count his fraud on his foundation, for example, his charity — there's a lot of state violations. We haven't seen his tax returns yet, but I'm willing to bet that there are some crimes there. But I'm not going to prejudge that until I see the evidence, and I believe the court will say that he has to turn them over or that his accounting firm has to turn them over.

I think we see a lot of parallels between Richard Nixon and Donald Trump. There is one human person that is actually involved in both, which is Roger Stone. Roger started working on the committee to re-elect Nixon, the youngest person on that team at the time, and now Donald Trump is interfering in the prosecution of his longtime friend Roger Stone.

It's not a coincidence. When you look at Richard Nixon and Donald Trump, which one do you think is a bigger threat to the rule of law and to the nation? Nixon at that time or Trump today?

No question that it's Donald Trump, because he has absolutely no respect for the rule of law. Remember, in the end Richard Nixon resigned because he accepted the rule of law. Remember, in the end he did turn over the tapes. He stonewalled as long as he could, but when the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision, he turned them over and that was his undoing. The "smoking gun" tape was part of it. Roger Stone is the least of what Donald Trump is doing to interfere with justice. All the pardons that he's issued recently are sending a message. His attack on the whistleblowers is all saying, "You better stick with me and don't do anything or you lose your job." I mean, his behavior and his empowerment by McConnell and the Senate, his empowerment by Attorney General Barr, has made him really have no guardrails.

It is sad. There was a recent New York Times op-ed by Admiral McRaven that talked about how the president is challenging democracy. It was very well written, very moving to me. It was so touching about the danger of Donald Trump. I really fear for democracy. If he is re-elected I lose all hope for democracy, and I'm not being overly dramatic. I really, truly do. Everything that he has done has been, I mean, the gender and racial bias is horrible. The rule of law is horrible. I'm not talking about his policies. I'm not talking about whether he's right or wrong on taxes. I'm talking about what he has done to unleash hatred in this country and to make us not a democracy anymore. I think it's a very serious thing.

It seems that Republicans, except for Mitt Romney, will do anything to save Donald Trump. Is the political world we live in today more concerning because of the enablers in the Republican Party as opposed to the Republican Party of 1974?

You've said it exactly correctly. I think one of the most painful hours of my life was listening to senators who had said yes, he did all the things he's accused of, we don't need more evidence because it's already proved beyond a reasonable doubt, say, "Not guilty." It wasn't a question of saying, "Not impeachable." It wasn't a question of saying yes or no, he should be impeached. The words they had to speak were "Not guilty," and that was such a lie that that was extremely troubling to me and should be to all Americans. It should lead to all those people losing their Senate seats when they're up for re-election.

Is Donald Trump how democracies die?

Yes. I know this is an offensive comparison, but I remember when I first moved to Chicago, a book by Herman Wouk called "Winds of War" and "War and Remembrance" came out and I was riding the train commuting to work reading that book and it was so realistic that I felt like I was on the train being taken to Dachau. I'm not comparing them. Please don't misunderstand me, but I have that same feeling. Hitler did not do one sweeping thing where everything in democracy is gone. He took away the rights one at a time. First, it was that Jews couldn't shop and thenthey couldn't own the shop and then they couldn't leave their homes. They had to stay in the ghetto. It wasn't all at once. You get desensitized. This whole thing about, you know, the boiling of the frog. They don't jump out because they just get used to it.

America, don't be desensitized. Don't forget that we're losing our rights, one at time. And when Donald Trump says, "Oh, I'm protecting pre-existing conditions," please pay attention to the fact that he's in court trying to kill them. These are the ways we lose our rights, one at a time, and we really need to catch up on it.

Shares