That Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont has a floor in this Democratic primary race is undeniable. His base of supporters has been enthusiastic and loyal, and apparently not even a little tempted to decamp to Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who has largely the same policy goals but a more detailed roadmap for how to achieve them. Sanders’ base has been an invaluable asset, creating a floor of support of about 20% below which his numbers never really dipped, even after he suffered a heart attack that threatened to end his campaign.

The only question really is whether or not Sanders has a ceiling — a level of support where he maxes out and cannot expand further— and how close to that floor the ceiling is. Would the self-described democratic socialist who isn’t a registered Democrat be able to win the majority of Democratic voters? How many people outside the Sanders base can be persuaded that he’s the Democratic Party’s best bet against Donald Trump in November?

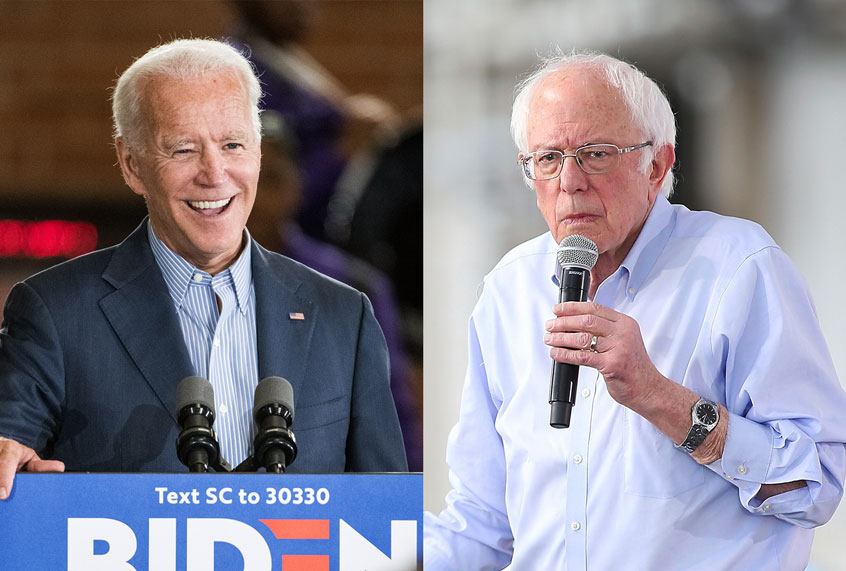

Unfortunately for Sanders, the results of Super Tuesday suggest he’s not doing a great job of winning over those ordinary Democratic voters that he needs to win the nomination. Former Vice President Joe Biden swept not just the Southern states that voted this week, but also won states like Massachusetts, Minnesota and Oklahoma. Biden edged out Sanders in Texas, where the latter has led the polls for several weeks. Yes, Sanders appears likely to win California by a substantial margin once all the votes are counted, but Biden will almost certainly hold a lead in pledged delegates after Tuesday, and may be ahead in the popular vote as well.

To be certain, the situation isn’t as cut-and-dried as headlines declaring which candidate won which state might suggest. Delegates are awarded proportionally, which means that while Sanders apparently did not “win” Texas, he’ll be close enough behind Biden to get a substantial chunk of those delegates anyway. This contest is still very much alive: It would be foolish to write Sanders off because he had a bad night.

But the results of Super Tuesday should trouble Sanders and his supporters all the same, because it’s not clear that Biden’s success has much to do with Joe Biden himself. On the contrary, it looks like the result of Democrats who aren’t comfortable with Sanders coalescing behind the one remaining candidate who seems best poised to beat him.

The New York Times’ analysis on Wednesday morning noted that Biden didn’t win on the strength of his campaign, since in many of those states he almost didn’t have one. Biden won “where he was overwhelmingly outspent in advertising” and “where rivals had a better organization” and even where he didn’t campaign at all.

If anything, there’s reason to believe that Biden does better the less voters see of him. He got hammered in the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary, the two states where voters get to see candidates up close and personal. Biden’s debate performances have been alarmingly poor. His speeches are rambling messes and he has a bad habit of making up odd stories with a flexible relationship to the truth. The Biden rally I attended in New Hampshire was a desultory occasion, while Sanders continues to hold rock-concert-level affairs.

Biden isn’t winning because he’s got some secret winning sauce. He simply seems to have consolidated the not-Sanders vote. He’s literally the last man standing: Sen. Kamala Harris of California and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey quit the race before the voting even started, and Biden worked some party-insider magic to convince Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former South Bend, Indiana Mayor, Pete Buttigieg to drop out right after the South Carolina primary. Now Biden is positioned as the last possible choice for folks who don’t want Sanders to be the nominee.

As Super Tuesday showed, there are a lot of people in that not-Sanders crowd. Sanders has argued on the campaign trail that he has a unique appeal and will win by turning out large numbers of voters who otherwise don’t turn up. Well, turnout was high Tuesday night, but it was driven in large part by suburban women, i.e., those “resistance wine moms” with their Women’s March buttons and oversized strollers who are such an object of mockery in Chapo Trap House circles.

There is little doubt in my mind that by saying this, I’ll get hammered on social media, trashed as an “identitarian” and a “neoliberal shill,” and accused of wanting people die from lack of insulin. (Despite the snake emojis tweeted at me, when the chips are down I prefer Sanders over Biden.) This “Bernie Bro” dog-pile tactic has been effective at silencing some online criticism of Sanders and his campaign, but as the results from Super Tuesday suggest, it’s not nearly as effective in bringing more people on board the Sanders train.

No, before you get typing, I’m not saying that the Bernie Bros are, in themselves, losing this race for Sanders. I fully agree that most voters, especially those pussy-hatted middle-aged moms who are too busy for Twitter, don’t have a lot of direct encounters with that set. But that annoying subculture is, unfortunately, the result of the larger Sanders tendency to approach the Democratic Party in the spirit of conquest instead of outreach.

The Sanders plan, as Ezra Klein wrote Wednesday in Vox, was to “sweep away the Democratic establishment and build his own party in its place,” presumably by bringing in so many voters that he wouldn’t need the existing ones.

Biden, on the other hand, “still has that legislator’s touch,” an ability to strike deals with political allies to gain endorsements and support. While Sanders’s campaign staff and most ardent supporters view “transactional politicking with contempt,” it’s also true that such outreach is necessary to actually win allies and build a winning voter coalition.

For instance, there is the case of Warren, who has not yet dropped out and endorsed Sanders, despite many public demands from Sanders supporters that she do so. (Apparently Warren is weighing her possible departure from the race on Wednesday. She will do it on her own terms, if and when that happens.) Klein asks “why Sanders hasn’t been able to convince her” and suggests, much as it may pain the Sanders camp to accept it, that offering carrots to Warren and her supporters might work better than constantly battering them with sticks.

The reality of it is that exactly what supporters say they like about Bernie Sanders — the fact that he’s been saying the same things for 40 years — might be hurting his ability to build a coalition. In particular, women over 40 and black voters don’t appear to be feeling the Bern, and that is likely in because Sanders’ messaging doesn’t prioritize issues that take precedence for many of those voters, such as gun violence, the rise of white supremacy or domestic violence.

Biden, on the other hand, has put the war against white supremacy and an anti-gun message at the center of his campaign, and can take full credit for his work on the Violence Against Women Act. So, even if voters don’t feel he’s the most charismatic or connected of politicians, he seems to be hearing their concerns and shaping his message to meet them.

Which isn’t to say that Sanders doesn’t have the right opinions on those issues — he does. But it sometimes feels like checking off the boxes, before getting right back to the class-based message about economic inequality he’s been pushing for 40 years. Which is important, of course, but may be a harder sell when the recent rise of an overtly racist and misogynistic president feels, to most Democrats, like an urgent development that needs immediate and focused attention.

As I said earlier, this campaign is far from over. It’s not clear at all which of these two men will win, or if either of them will go into the convention in July with a clear majority of delegates. But the results also suggest that the Sanders ceiling is very real and that he could now face a situation where many Democrats, however quiet they may be about it, are voting against Sanders more than for Biden.

Ironically, this is the very situation that Hillary Clinton faced in 2016, when she won the nomination but struggled to get the people who had voted for Sanders — specifically because they disliked her — rallying to her side in November. If Sanders’ outreach to reluctant voters doesn’t improve, he might be stuck in the shoes of the woman who became his enemy the last time he ran for president.