The book world has had a tumultuous 2020 so far, starting in January with the raging controversy around Jeanine Cummins' inevitably bestselling novel "American Dirt," which critics, Latinx writers in particular, dismantled for relying on stereotypes, appropriated reporting and falling far short, on both literary and social merits, of its cover blurb claiming to be "a 'Grapes of Wrath' for our time." The "American Dirt" discourse hasn't faded — in fact, an Oprah's Book Club special in which Cummins "faces her critics" began streaming Friday on Apple TV Plus.

Meanwhile, dozens of Hachette Book Group workers walked out on Thursday to protest the planned publication of Woody Allen's memoir, which had been set to be published by its Grand Central imprint in April. One of the leading voices speaking out against Allen's book deal was his estranged son Ronan Farrow, who has been an outspoken advocate for his sister Dylan in support of her longstanding claims that Allen sexually abused her when she was a child. Ronan Farrow is also a Hachette author, having published his devastating book about his investigation of the Pulitzer-winning Harvey Weinstein story, "Catch and Kill," with Little, Brown. Farrow had indicated he would cut ties with Hachette over their decision to do business with Allen, and on Friday afternoon we learned that the protests worked and Allen's book had been dropped by Grand Central.

Then coronavirus made book travel an uncertain proposition for the near future. While the annual AWP conference went on as planned this week, many authors and small presses opted to stay home from the otherwise don't-miss event.

But let's not let that overshadow the excellent new books due out this month, just in time for spring break or primary season distraction (or illumination, depending on your needs). On March 10, Rebecca Solnit's "Recollections of My Nonexistence" — a memoir from the feminist author of "Men Explain Things To Me" — is due out from Viking, and you can read Salon's Amanda Marcotte interview with Solnit in which she discusses her anti-memoir, Elizabeth Warren, and punk rock. Progressive economist Robert Reich's "The System: Who Rigged It, How to Fix It" is coming from Knopf on March 25. Don't want to wait for a new read? Edited by Lizzie Skurnick, "Pretty Bitches," an anthology of essays on the words used to undermine women, features a powerhouse lineup of contributors, from Glynnis MacNicol and Laura Lippman to Monique Truong and Afua Hirsch, is already out from Seal Press.

Fiction readers have an abundance of intriguing choices this month. Look for Kate Elizabeth Russell's much-anticipated "My Dark Vanessa," a novel about a teenage misfit at boarding school groomed for sexual abuse by her charismatic English teacher, out on March 10. (Read the Salon interview here.)

Maisy Card's debut novel "These Ghosts Are Family" (March 3, Simon & Schuster) travels back and forth in time between colonial Jamaica and present-day New York to explore how a man's long-buried secret affects the women in his family. And also out now from Riverhead, Celia Laskey's debut novel "Under the Rainbow" sends a queer "task force" to a fictional Kansas locale dubbed "The Most Homophobic Town in the U.S." to live for two years as a social experiment.

Series fans can have a little reading, as a treat: Hilary Mantel completes her acclaimed Thomas Cromwell trilogy that she launched in 2009 with "Wolf Hall" on March 10 with "The Mirror & The Light" (Henry Holt and Company), and eerie fictional podcast "Welcome to Night Vale" creators Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor add to their growing "Night Vale" expansion bibliography with "The Faceless Old Woman Who Secretly Lives In Your Home" (Harper Perennial, March 24).

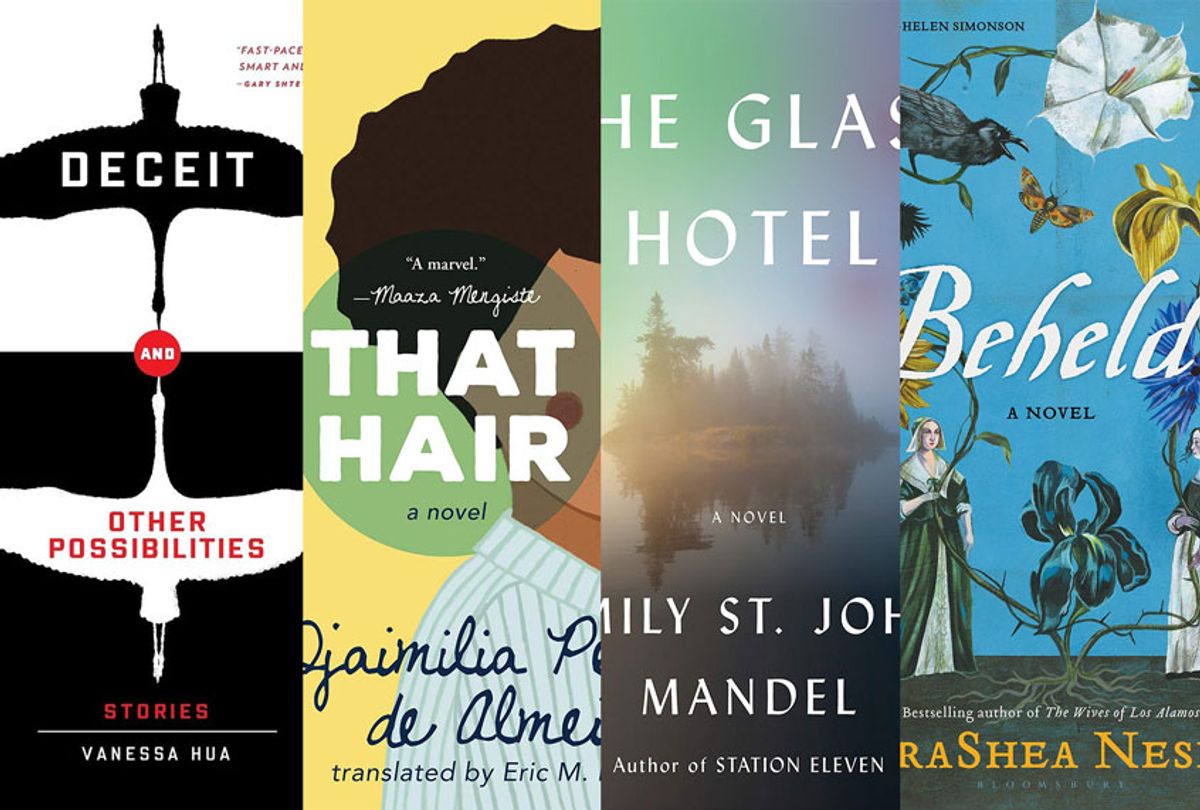

And here are closer looks at six books out this month that caught the eye of Salon staff.

"The Body Double" by Emily Beyda (Doubleday, March 3)

Get ready for this glamorous yet disturbing debut by Emily Beyda, who grew up in Los Angeles and once worked for the family of a famous Hollywood star. Those experiences inform "The Body Double," in which a young woman is hired by a mysterious man named Max to masquerade as a well-known but now reclusive celebrity known as Rosanna Feld. But soon, she realizes that this is not just a fun jaunt living as the rich and famous, but a strictly orchestrated performance in which her every move, intonation, and look is controlled by Max.

While the story draws obvious comparisons to "Vertigo," another Hitchcock classic "Rebecca" also comes to mind. In both, a woman is overshadowed by another who has come before, but is never seen. "The Body Double" makes the original Rosanna a palpable presence in the mind of the novel's protagonist, who, like the heroine in "Rebecca," is never named, but speaks in the first person.

Beyda creates a constant state of unease with the very namelessness of the protagonist. She is absolutely a victim, but it's difficult for the reader to sympathize with her completely because of how clearly damaged she is to put up with this treatment. She is an unmoored individual, hungry for all the benefits that Max bestows upon her, and willing to put up with the emotional abuse that's attached. And as with any good Tinseltown noir, there are darker elements afoot that the reader will cotton to earlier than the faux Rosanna does.

"The Body Double" contains all the sinister elements that have always been present in any Pygmalion story: the male gaze, controlling and defining womanhood, co-dependence and loss of identity. And Beyda creates this deliberately with extensive focus on the body as the narrator works on her diet, exercise, skin regimen, movements and facial expressions to better mimic Rosanna. "The Body Double" is a darkly sensual story, but rather than veer into the psychosexual, it instead comes down to one woman's decision about who ultimately commands her life. — Hanh Nguyen

* * *

"Docile" by K.M. Szpara (Tor, March 3)

In the world of "Docile," created by KM Sparza, a dystopian America has been reduced to essentially two classes — trillionaires and those absolutely crushed by debt. The middle class has ceased to exist as the "Debtor" class inherits their family members' debt, meaning it accumulates over time and generations. Some opt to pay off their debt by entering into indentured servitude for a predetermined amount of time; some also opt to be injected with a drug called Dociline, which leaves them with no memory of their term but strips them of any agency.

It's supposed to wear off within two weeks, but that wasn't the case for Elisha Wilder's mother. When she returned from her servitude, Dociline seemed permanently trapped in her system, rendering her forever docile.

As a way to pay off the rest of his family's debt, Elisha becomes a servant to Alex Bishop, the CEO of the company that manufactures Dociline, but opts out of taking the drug. This puts Alex in an uncomfortable position — he has to deal with Elisha as a fellow human rather than a robotically cheerful Docile — that forces him to reckon with his place in a cruelly unbalanced society.

Told in alternating perspectives, we watch as Elisha struggles to maintain his sense of personhood as he comes to terms with his attraction to Alex, while Alex struggles to recognize Elisha as something other than a "c*cksucking robot."

"I am Dr. Frankenstein and I've fallen in love with my own monster," says Elisha at one point.

Sex, sexual abuse and rape are all central themes in "Docile." It's a complicated book that has fully-realized queer characters who introduce and examine topics that sometimes seem impenetrable, like oppression and coercion.

But one way in which "Docile" notably misses the mark is in its discussion — or rather lack thereof — of the history of institutionalized, racially-based slavery in the United States. This novel is classified as "alt/near-future" fiction, but with the current state of America, topics of race, socioeconomic and servitude class seem inextricable.

That said, "Docile" is a gripping work of science fiction that punches up in the direction of the current powers that be.

* * *

"Deceit and Other Possibilities: Stories" by Vanessa Hua (Counterpoint, March 10)

Vanessa Hua made her startling and impressive debut in 2016 with her collection of short stories about the immigrant experience in America. Four years later, the book has been republished, doubled in size with brand-new stories that reveal that Hua was no fluke. Her writing is as sharp, insightful, witty, and heartbreaking as before. But with the passage of time, there's also wisdom.

There's the story of the Stanford student who is as fake as her doctored transcript, or the idol who can't escape a sex scandal of his own devising. Then there's the golfer who avoids thinking of the "prank" he played on his girlfriend, or the widow who goes on her first camping trip alone on the anniversary of her husband's death. Hua also tells of the Mexican boy in America who fights to keep his family together, and the tale of a Christmas dinner that is anything but festive.

Hua's brisk yet blunt storytelling style doesn't waste time with sentiment, as story after story follows these various characters who practice deception. In some cases, the lying is a straightforwardly selfish act, but in others, the lying is born from necessity or an attempt to keep the peace. Regardless of the motive, the deception is never easy, and Hua is able to find that tension point and tease it out for the reader to either anguish over or celebrate.

The majority of the stories told involve Asian Americans — Taiwanese, Korean, Japanese, hapa, among others — and in this way, Hua destroys the stereotype of the model minority along with the idea of a monolithic race. Yet, she revels in specificity — such as the guy who feels superior witnessing his sister's lack of skill with chopsticks — which imbues each story with emotional authenticity even as she's mocking the plight of her poor characters. Switching from male to female, young to old, fresh off the boat to third generation, Hua is able to find convey the lived experience in each, and her assurance with pacing and character prove that she's a master of the short story format. – H.N.

* * *

"Beheld" by TaraShea Nesbit (Bloomsbury Publishing, March 17)

By now we all know that the true story of the Mayflower Pilgrims and their Plymouth Colony is much darker and more layered than the simplistic "First Thanksgiving" fairy tale, about upright religious freedom-seekers making it in a harsh new climate with the help of their magnanimous Native American friends, which had been taught for generations to American kindergarteners. "Beheld," an elegantly suspenseful historical fiction account of a murder in Plymouth by TaraShea Nesbit, the bestselling author of "The Wives of Los Alamos," further complicates the narrative of the early colony. Using the points of view of two compelling women occupying different rungs of power in their community, "Beheld" dives deep into the history of the early American Massachusetts settlement to illuminate what Puritan Governor William Bradford left out of his foundational historical account, "Of Plymouth Plantation."

Bradford's genteel second wife Alice and the fiery Eleanor Billington, an Anglican woman and former indentured servant not interested in the least in submitting to "proper" Puritan customs, are the stars and focus of "Beheld." Through Eleanor's eyes, and those of her husband John, Nesbit shows America's classist roots run as deep as its racism, both of which contribute to the violence in early Massachusetts. Eleanor's awareness that something's rotten in the future state of Massachusetts is present from the start, but Alice's growing suspicions about how she came to be the Governor's wife show how deeply the personal corruption of elevated men can affect those who serve under them.

After their period of indenture expired, former servants like the Billingtons remained subjugated economically and culturally by the Puritan elites, led by Bradford and the brutal military adviser Myles Standish, even after being granted land of their own. The particulars of land disbursal lead eventually to resentments boiling over and a murder — not the first near Plymouth, as the head of a Wampanoag and the bloody linen Standish carried it in flying atop the meetinghouse attested, but the first between white people, or at least the first impossible not to cover up.

The murder is guaranteed to unnerve the English investors en route to check in on Bradford's progress and the colony's debt, as is John Billington's willingness to tell the truth about life in Plymouth. In "Beheld," debt is a menace to all, one way or another, giving this historical account a powerful resonance today. — Erin Keane

* * *

"That Hair" by Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida (Tin House Books, March 17)

As one might surmise from the title of this captivating and slim volume, what sits on narrator Mila's head is of utmost importance. And yet, by her own admission, she is afraid of writing about something that could seem frivolous. What de Almeida accomplishes in just under 150 pages is anything but that.

Of Portuguese and Angolan ancestry, Mila is a biracial woman whose hair tells the story of her ancestors . . . but also connects her with an American who lived before she was born. Mila's hair, you see, is more than just locks and follicles, but a complex connector to the struggles of living in the spaces in between. Neither African nor European, neither Christian nor Jewish, neither proud nor ashamed — Mila is all of those things and none. This is a story of colonialism, feminism, racism, love and expression. But most of all, it is a story of identity.

Translated by Eric M.B. Becker, the English-language version of "That Hair" maintains the gorgeous and sometimes elliptical expressions that Mila employs. Told in a meandering style that layers fiction on top of semi-autobiographical essay, the tragicomedy shuttles back and forth through time to visit Mila's grandfather, or her mother, or perhaps paternal great-grandmother this time — in a stream-of-consciousness narrative memory. And peppered throughout these pieces of her ancestry, her DNA, her influences, are the recollections about her curly hair and how she feels about it at that point in time.

"That Hair" may not offer the most linear storytelling — and in fact, every digression is dense with meaning and tangents — but what emerges is a surprisingly beautiful feeling of connection and rootedness. Between the journeys of her family members and her own experiences, Mila is still trying to define who and what she is, but that's as fruitless as trying to find just one way to dress her hair. And in the end, that mutable quality is the making of Mila. — H.N.

* * *

"The Glass Hotel: A Novel" by Emily St. John Mandel (Knopf, March 24)

Her 2014 blockbuster survivor epic "Station Eleven" may have eerie resonance now as pandemic fiction interest grows with the spread of coronavirus, but Emily St. John Mandel has moved on to a new story about societal collapse in this haunting novel about the 2008 financial crisis and the lengths people will go to deceive themselves about their own capacity for corruption.

"The Glass Hotel," about a Bernie Madoff-like character whose Ponzi scheme funds the life of the beautiful and talented Vincent, a former bartender traumatized by her mother's death who decides to become a trophy quasi-wife, a dependent — because it's easier, in the end, than the self-sufficiency she'd practiced since youth — after a disturbing incident at the titular hotel involving her tortured half-brother Paul, a heroin addict in and out of rehabs and relapses. Mandel once again shows to great devastating effect how precarious a society is when maintaining it depends on relying on people to be worthy of trust. – E.K.

* * *

"It's Not All Downhill From Here" by Terry McMillan (Ballantine Books, March 31)

Like Terry McMillion's past beloved works like "How Stella Got Her Groove Back" and "Waiting to Exhale," "It's Not All Downhill from Here" is an unmitigated delight with inevitable blockbuster potential.

We're introduced to a close-knit group of black women in their 60s. There's protagonist Loretha Curry, a beauty supply mogul still enamored with her third husband Carl; the wealthy, cruise-loving widow, Poochie; Kornythia, a statuesque exercise instructor; Sadie, a church lady with a secret life; and Lucky, who married a white architect and commiserates with Loretha about their respective struggles with weight gain.

When Carl suddenly dies of a heart attack, Loretha leans on her girlfriends to share grief, laughter and confessions about her regrets in life. Loretha's estranged daughter Jalecia is an alcoholic who is living on the streets, she's completely removed from the life of her twin sister, and her son lives in Japan. As Loretha says, "being ambitious can backfire when you're black, a woman, and a mother."

"It's Not All Downhill from Here" is a deeply moving book that gently balances the realities — both personal and societal — of aging with a hopeful message: It's never too late to change how you're living your life. – A.D.S.

Shares