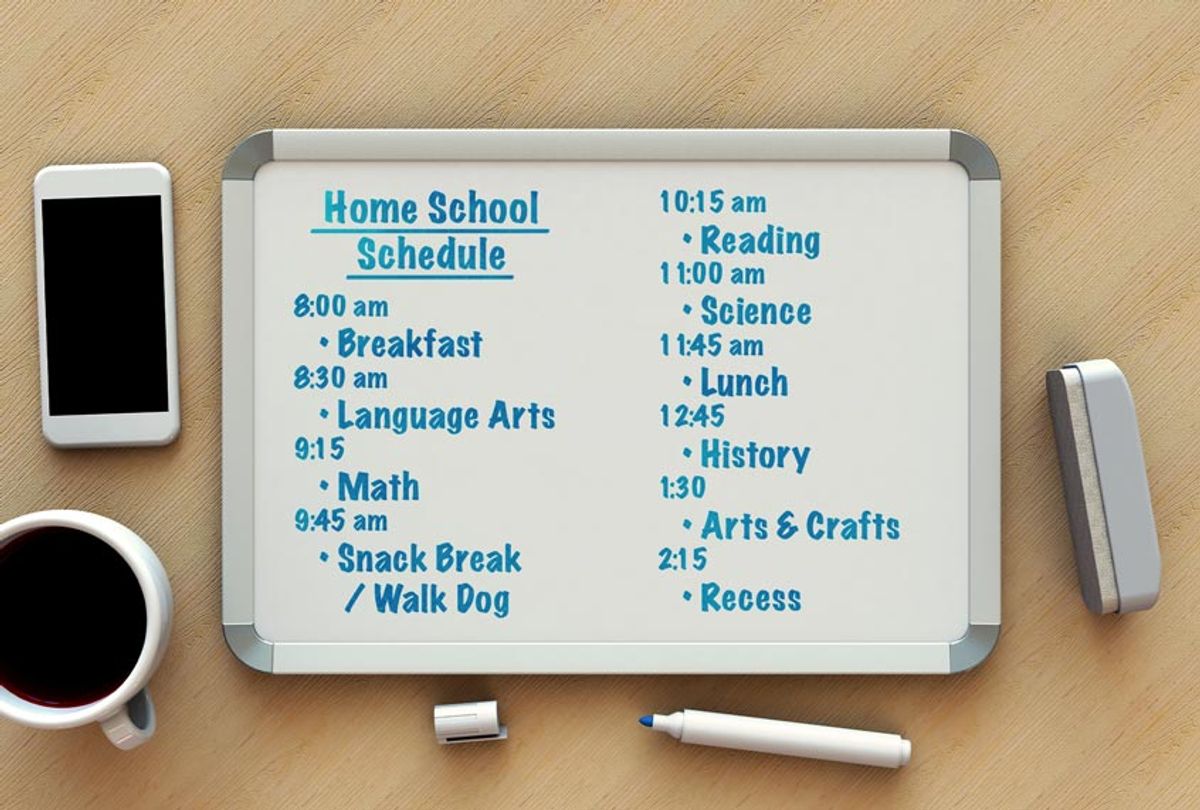

I keep seeing them on social media: The "school schedules" written on kitchen whiteboards, shared proudly by parents newly tasked with home schooling in the face of a pandemic. Those whiteboards make my heart sink — they send me straight back 22 years.

My oldest was five. We were just starting out as home-schoolers. I wrote out detailed lesson plans, as I'd done in my four years as an elementary school teacher. Henry loved my plan for building a house from a refrigerator box; he spent hours on it. Studying a diagram in a book, he managed to make a door handle from a thread spool. It had a cardboard latch that locked when he turned it.

The rest of my plans didn't thrill him. When I asked him to fill in a graph at the kitchen table, he slumped and grunted. I was his mother, not his teacher, and he didn't care about pleasing me. He liked hearing "This is the House that Jack Built," but when I suggested we write our own version of the story — a classic literary exercise in 1990s classrooms — he kept painting the door of his cardboard house.

"That's dumb," he said. "Somebody already did it."

I continued pushing my plans, but began to wonder what he was learning from the tasks that set him grumbling. He seemed to be learning that he didn't like math. Or writing. Or whatever I was trying to sell that day.

It was different when he worked on his cardboard house. When he drew a pirate ship from an Ed Emberley book. When he played Peter Pan with his younger sister after I read the book aloud. At those times there was a gleam about him. A focus that said don't interrupt this.

In other words: He was learning.

I knew I ought to chase that gleam, but it was hard. I stopped writing daily plans, but an agenda hovered in my mind. The kids were most engaged when they played. Playing is how kids are wired to learn — I knew that. Still. Henry and Lily would be flying through the hallway as Harry and Hermione, and I'd want them to stop so we could get to some science, but then they'd start sketching puffapods and bubotubers in their Herbology journals and how could I interrupt that?

How would we ever get to all those school subjects? How many days would pass before we'd get back to math?

I tried to make the tedious parts easier. I took dictation so they could convey their ideas while their handwriting caught up with their minds. I found math based in games and real-world situations, but mostly we just worked through it quickly and more intermittently than I'd have liked. Every two days? Three?

I constantly worried we weren't doing enough.

I'd read to them for hours. Fiction. Nonfiction, on everything from trebuchets to supernovas. We really ought to make timelines, I'd think, but they'd want one more chapter of "The Return of the Great Brain." And then they'd want to debate the author's choices. And then they'd dash up to their rooms to listen to audiobooks while building with LEGO or stitching gnome clothes from felt.

I should be doing more, I worried.

They always had ideas about what they wanted to make, do, and write about. Sometimes they chose traditionally "academic" topics — desert animals, the American Revolution. More often it was something like Pokémon or Broadway musicals, Batman or "Backyard Baseball," an utterly mindless computer game.

And then, they started connecting it all: John Muir met Teddy Roosevelt in Yosemite in 1903, and hey! that was just a few years before All-of-a-Kind Family dressed up for Purim on the Lower East Side, and hey! that's near Ellis Island where Kirsten's family came off the ship from Sweden, but wait! that was about 50 years earlier and hey! that's right when the New York Knickerbockers started inventing the rules of baseball!

I relaxed. I let them pursue whatever engaged them. Henry made camcorder movies by the dozen, often featuring his siblings as elves and a Led Zeppelin soundtrack. Lily made cupcakes and gnocchi and crepes, narrating every step like a cooking show host. Theo read nothing but comics and atlases and books with titles like "Ultimate Weird but True." He spent months making a periodic table of Marvel characters.

Their projects took so much time. I worried at all we weren't getting to, but then I'd see how Henry was reading Truffaut's interviews with Hitchcock. How Lily had internalized fractions from doubling recipes. How Theo could explain all he'd learned from comics: about women's shifting roles through the decades, Captain America's morale-boosting origins during WWII, Black Panther's creation in the era of civil rights.

It was more than enough.

I feel for all these parents now, thrust into a home-schooling world they didn't choose for themselves, while trying, in many cases, to work from home at the same time. I hope they learn to ditch those whiteboard schedules and stop trying to replicate school. I hope they take this opportunity to give kids what they could use more of: independence, time for play. If schools are assigning work, I hope families can get through it quickly so there's time for stories. For games. For art. Time for those kids to pursue whatever sets them gleaming.

For my children, the strategy of relaxing worked. My oldest, that kid who made ridiculous movies about elves? He's now a cinematographer in Brooklyn — one of his recent projects was the Netflix documentary "Fyre." The girl who narrated her own cooking shows now works for a nonprofit as a food educator in — when they're open — New York City public schools. And my youngest, who binged on comics and atlases, is (presumably) off to college this fall, planning to study international relations — and comedy.

I never could have planned such futures for them. I'm grateful they didn't let me try.

Shares