During a rambling two-hour press conference on Tuesday evening, Donald Trump braced the country for a "very tough two weeks" – after which, he said, things will "get better all of a sudden … like a burst of light."

And for this, certain elements of the White House press corps exclaimed over the latest plot twist — Trump gets somber! — and hailed him for finally accepting reality.

But Trump did no such thing, as he subsequently made clear at Wednesday's briefing, an irrelevant but highly Trumpian detour into paranoid race-baiting about Latin American drug smugglers and his beautiful border wall.

Yes, Tuesday marked Trump's first public acknowledgment of the true scale of the disastrous coronavirus pandemic. But reporters largely ignored that it was accompanied by yet another round of magical thinking on his part — not to mention his continued insistence that his leadership has been beyond reproach.

You'll remember how Trump said in late February that "within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero." He predicted that "It's going to disappear. One day — it's like a miracle — it will disappear."

On Tuesday, he was still predicting miracles. He just modified the timeframe:

I want every American to be prepared for the hard days that lie ahead. We're going to go through a very tough two weeks. And then hopefully as the experts are predicting, as I think a lot of us are predicting after having studied it so hard, you're going to start seeing some real light at the end of the tunnel, but this is going to be a very painful, very, very painful two weeks. ...

As a nation, we face a difficult few weeks as we approach that really important day when we're going to see things get better all of a sudden. And it's going to be like a burst of light — I really think and I hope.

At one point, he said "maybe even three weeks."

Even if you ignore his "burst of light" fantasy, by the way, the figures the White House displayed on Tuesday show that in the best-case scenario, the national death rate peaks in 15 days. That doesn't mean the horror ends. In fact, looking at the total projected fatalities from this pandemic, more than two-thirds will occur after April 15. So in 15 days, the worst will still be yet to come.

Nevertheless, New York Times chief White House correspondent Peter Baker saw what he wanted to see:

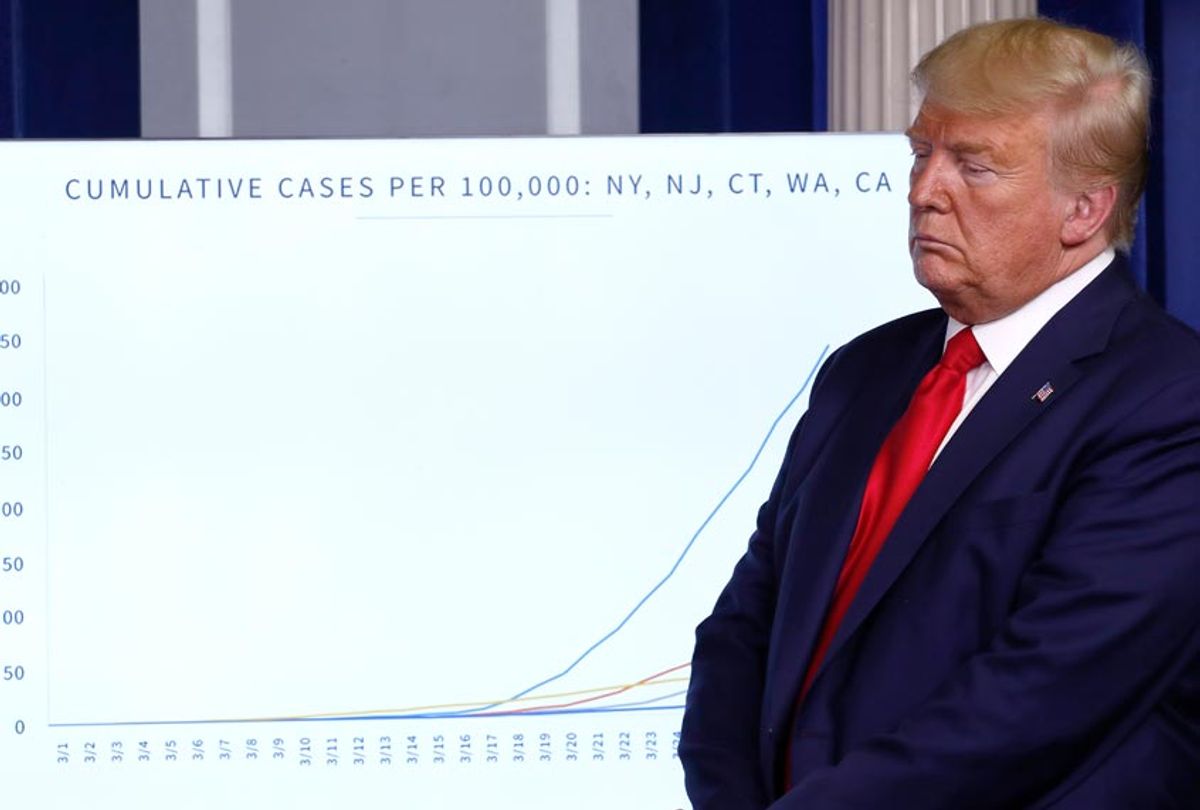

The grim-faced president who appeared in the White House briefing room for more than two hours on Tuesday evening beside charts showing death projections of hellacious proportions was coming to grips with a reality he had long refused to accept ….

A crisis that Mr. Trump had repeatedly asserted was "under control" and hoped would "miraculously" disappear has come to consume his presidency, presenting him with a challenge that he seems only now to be seeing more clearly.

Philip Rucker and William Wan wrote in the Washington Post:

Trump adopted a newly somber and sedate tone — and contradicted many of his own previous assessments of the virus — as he instructed Americans to continue social distancing, school closures and other mitigation efforts for an additional 30 days and to think of the choices they make as matters of life and death.

James Hohmann wrote for the Post:

The president's newfound respect for — and deference to — experts, careerists and technocrats is part of an even more dramatic shift in his tone over the past few days as the gravity of the crisis enveloping the country appeared to fully sink in.

CBS News anchor Norah O'Donnell intoned: "It seems like today is the day the reality of the staggering death toll hit hard at the White House."

It was so predictable as to be depressing. Here's part of a Twitter thread from NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen:

On NPR's "All Things Considered," host Ailsa Chang told listeners that "President Trump prepared the country for the difficult days ahead in tonight's coronavirus task force briefing."

Fortunately, science writer Richard Harris brought some needed clarity to the matter:

Well, they finally laid out the data from the models that they've been using. And the basic idea that they tell, the story they tell, is this whole thing will peak in about mid-April if the models are correct, and then it will slowly fade. It will not be the burst of light that the president referred to, but more of a long deep sigh. Dr. Anthony Fauci from the National Institutes of Health says cases will gradually fall after the peak, but we'll be seeing deaths for some time after that because time elapses between the time a person's case is reported and an eventual death.

And while it came late in Tuesday's seemingly endless news conference, Trump engaged in a fascinating exchange with CNN's Jim Acosta that's worth examining at length. The president attempted to assert a number of contradictory claims to the effect that he knew all along how severe the crisis could be, but that he didn't want to be negative, but that he was being negative, but that it would be all over soon:

Acosta: Going back to your comments about what could have happened and the actions that you took, is there any fairness to the criticism that you may have lulled Americans into a false sense of security when you were saying things like, "It's going to go away."

Trump: Well, it is.

Acosta: And that sort of thing.

Trump: It's going to go away. Hopefully at the end of the month and if not it hopefully will be soon after that.

As for his previous optimism:

Trump: I think from the beginning, my attitude was that we have to give this country … I knew how bad it was. All you have to do is look at what was going on in China. It was devastation. Well, yeah, look at the numbers from China, those initial numbers coming out from China. But I read an article today which was very interesting. They say, "We wish President Trump would give more bad news." Give bad news. I'm not about bad news. I want to give people hope. I want to give people a feeling that we all have a chance …

Acosta: You weren't just hoping that it would dissipate, that this would disappear?

Trump: I want to be positive. I don't want to be negative…. I'm a cheerleader for the country. We're going through the worst thing that the country's probably ever seen. Look, we had the Civil War, we lost 600,000 people, right? Here's the thing, had we not done anything, we would have lost many times that, but we did something and so it's going to be hopefully way under that, but we lose more here potentially than you lose in world wars as a country. So there's nothing positive, there's nothing great about it, but I want to give people in this country hope. I think it's very important.

Acosta: Did you know it was going to be this severe when you were saying this was under control and —

Trump: I knew everything. I knew it could be horrible and I knew it could be maybe good. Don't forget, at that time people didn't know that much about it. Even the experts, we were talking about it. We didn't know where it was going …

But I don't want to be a negative person. It'd be so much easier for me to come up and say, "We have bad news. We're going to lose 220,000 people and it's going to happen over the next few weeks." And with that, I did start off by saying today, long before this question, I said, "This is going to be a rough two or three weeks." This is going to be one of the roughest two or three weeks we've ever had in our country. We're going to lose thousands of people ….

When you see the kind of numbers that we're witnessing, we've never seen numbers like that. So it's easy to be negative and then everybody could be negative. But I'm a cheerleader for our country, and I want to do a great job so the number can be kept … and I've always said it. I want as few a number of people to die as possible and that's all we're working on.

So here's a clause reporters can use next time Trump shares ridiculously optimistic projections that have no basis in fact: "Trump, who has previously acknowledged that he is 'not about bad news' …"

Politico editor John Harris has a new essay out making the now-tired argument that Trump's "bluster, defiance, implacable self-promotion" have "served him quite well" in the past, but no longer. He concludes:

If there is any common trait of failed presidents, it is incapacity for growth — a reliance on old habits and thinking even when events demand the opposite.

Elite political reporters keep trying to write about how Trump is changing. But he never will.

Shares