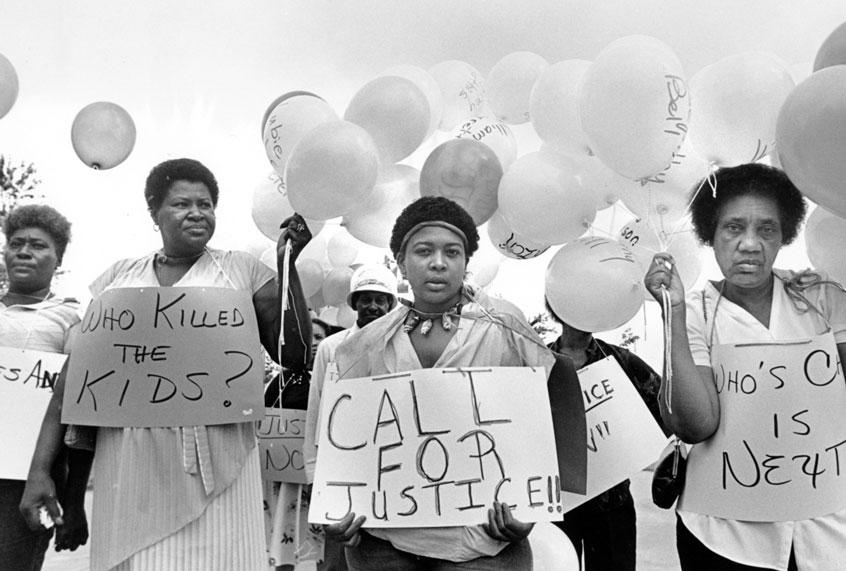

Over the course of three years, 1979 to 1981, at least 30 African American children and young adults in Atlanta were abducted and killed. Wayne Williams, a young black man, was subsequently arrested and charged with all the murders. At the time, city officials largely made it appear as if it were an open-and-shut case of a serial killer.

But four decades later in 2019, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms reopened the case, and “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children,” a five-part HBO documentary series, explores the inconsistencies and unanswered questions surrounding these horrific, brutal killings that led to that decision.

The lines are drawn right away. Most of the families of the victims aren’t convinced Williams is the killer (Williams has maintained his innocence throughout) and a lot of journalists and community members are also skeptical. Government and law enforcement officials, however, are staunchly convinced they have the right man serving life in prison.

The first episode opens on Atlanta in the 1970s, a city that was lauded as a shining example of black progress, especially once Maynard Jackson became mayor, backed by the leaders of the flourishing black business district. But then the bodies of two teenage boys were found in the woods, and then the body count just kept rising and rising.

“Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered” is not an easy watch, nor should it be. Directors Sam Pollard, Maro Chermayeff, Jeff Dupre and Joshua Bennett rely on sobering archival footage of nightly news stories about the murders, stills of the victims, and many videos of funerals with child-sized caskets being lowered in the ground.

But the documentary also captures what a bizarre, morbid media circus the cases wrought, and how Atlanta officials, who had spent the last decade attempting to boost the city’s reputation as a destination for business and tourism, bristled under the eye of federal agents and the nation at large.

While President Ronald Reagan was making statements about how the White House would do everything they could to help, Camille Bell, the mother of one of the victims, said the Atlanta police “couldn’t even catch a cold.” Within short order, things took a turn for the weird as psychics were flown in to see what they divine about the situation, and Bill Cosby starred in a “stranger danger” public-service announcement.

What leads to a supposed break in the case only inspires the killer to begin taking measures to shift his/her M.O. to destroy evidence. Therefore, much of the evidence used to pin dozens of murders on Williams is circumstantial at best, but what “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered” does well is, instead of just casting doubt on the conviction and revealing missed leads and suspects, it really gets to the heart of why officials were so quick to try to close the cases. Unsurprisingly, a large part of this points to racist hate groups, but such leads were ignored by investigators at the time because that didn’t fit with Atlanta’s inclusive reputation – but it was not ignored by the series’ filmmakers.

When Mayor Bottoms and Atlanta Chief of Police Erika Shields announce that they would be reopening the investigation, Shields makes the statement, “Do I think that, in some of the cases, there will be a different suspect? Yes.”

“Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered” asks what a new, different suspect would mean for the families. Yes, this is a true crime story, as well as one that delves into matters of guilt, innocence and a broken (often historically racist) criminal justice system — but it’s also a contemplation of what closure actually looks like for those affected by violent, race-based crime. There’s no clear answer, just as there is still no clear suspect in all the murders, but what this docuseries makes obvious is a community’s responsibility to ask questions for and advocate on behalf of its most vulnerable members.

“Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children” premieres on Sunday, April 5 at 8 p.m. ET.