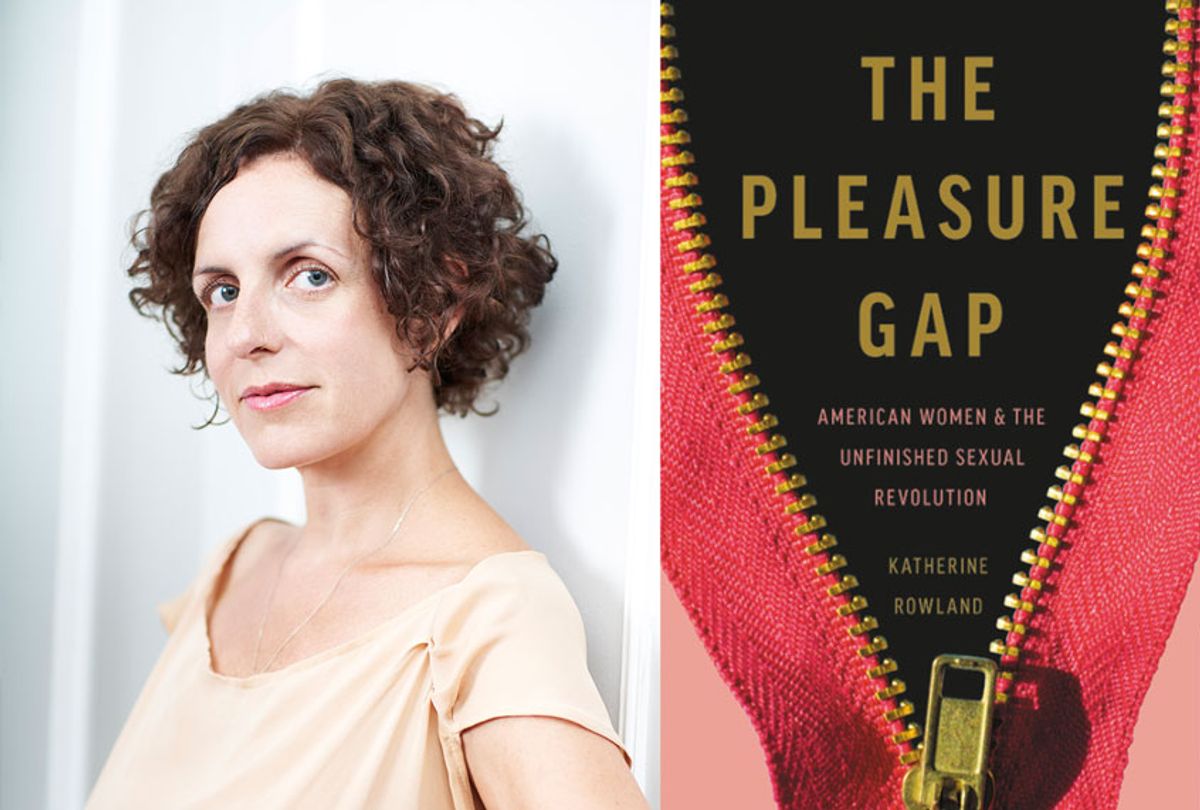

Women are plagued by damaging stereotypes about how they do and don't experience pleasure. This is part of the reason that studies generally indicate that women have fewer orgasms than men. Understanding how external factors such as social messaging, long-term monogamy, financial woes and gendered violence contribute to sexual dissatisfaction form the crux of a new book by Katherine Rowland, titled "The Pleasure Gap: American Women and the Unfinished Sexual Revolution."

In her book, Rowland, who is also a public health researcher, explores how and why there is still sexual pleasure gap despite advancements in gender equality. Rowland interviewed 120 women, as well as dozens of health professionals and researchers in her mission to explore society's counterproductive relationship with women's sexuality. That makes the book a must-read on a topic that is often dismissed.

Salon interviewed Rowland about her work; as always, this interview has been condensed and edited for print.

What inspired you to pursue this topic?

Prior to writing the book, I'd spent years looking into different aspects of women's sexual health, but what really got me going on the subject of pleasure was the push to bring a so-called "female viagra" to market between 2014 and 2015. All of a sudden, dire statistics were in circulation, claiming that 43 percent of women suffered from sexual dysfunction and that low desire was a medical malady that warranted a medical, or in this case, pharmaceutical intervention. But missing in all of this was any agreed-upon definition of what constitutes healthy or normal desire. How are we to define, let alone quantify, something as subjective and changing as sexual appetite?

I saw the conversations surrounding the little pink pill as pathologizing women. The underlying assumption was that if women did not want to have sex, it was not a matter of circumstances eroding their appetites — the careless partners, the enervating bedroom routines, kids, caretaking, unforgiving work-life schedules. It was rather that desire was presented as existing in a black box, seemingly impervious to context: there one day, vanished the next. If it dipped or disappeared that was an indication of something wrong with women's minds and bodies.

So I set out to talk with women about the nature of their own lust, to get a fuller picture of what turned them on or off, and how they understood the terms of their own pleasure. And what I found in the course of my reporting was that low desire was not a widespread medical malady. It was, by and large, a healthy response to lackluster and unsatisfying sex.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book?

The most challenging part was continually running up against women's stories of pain, trauma and transgression, and feeling ill-equipped to help or offer solace in a sustained way. I went into this project well-versed in the statistics describing sexual violence and assault, and yet I still felt unprepared for the near-ubiquity of women's experiences of violation. After all, I set out to write about pleasure. But what I found was that pleasure, delight, and desire — really the full spectrum of sensation, even the ability to feel — was closely tethered to, and circumscribed by pain. Women told me about being abused by partners, strangers, and family members. A large number were victimized in early childhood. And these horrible encounters continued to ripple across their bodies and minds, altering their self-concept and really infecting their self-worth.

A big part of the problem here is that sexual trauma requires sexual healing — that is learning to experience sexuality as safe, healthy, and even transformative. But because our society tends to swaddle sex in shame and misunderstanding, it can be hard for women to approach sexuality in such positive terms.

I was wrapping up my reporting as #MeToo gathered steam, and it was equal parts heartening and heartbreaking to behold this outpouring of truth. But I admit, I was, and I remain troubled by the extent to which #MeToo and the larger nexus of conversations on consent tend to erase the subject of women's desire. We cannot stop at the simple delineation of bad sex is unwanted and good sex is consensual. We have to start thinking about consent in ways that encompass women's longing and actual sexual agency, their ability to safely feel and express their desires, not just their ability to say no.

One of the main questions of the book is "How can more women give themselves permission to experience sexual pleasure?" You call this the "unfinished sexual revolution." What do you think can be done in society to give women the space to do that?

The unfinished sexual revolution is a facet of larger systemic inequities that work to enforce or naturalize the idea that women deserve less than men. Addressing sexual inequality — women's right to feeling, to pleasure, and to safely and freely articulate and pursue what they want and need — is by necessity part of the larger project of faithfully promoting human equality.

I think there are also a number of more direct interventions. First off, we need to radically alter the way we teach and talk about human sexuality, so that desire and anatomy are not warped by shame, and so that mutual pleasure is understood to be a feature of public health. Second, we need to address sexual violence as the public health crisis that it is. It's completely unacceptable to have a huge swathe of the population living in a state of conscious or semiconscious fear of victimization. This compounds the chronic objectification and self-censorship that so many people contend with.

Third, and this links to the structural issues, we need to reassess the ways we allocate capital and carework according to gender. Even though modern partnerships are increasingly founded on democratic and companionate principles, when you peer inside the inner workings you often find tired stereotypes very much intact. Frankly, in a capitalist society with its crude assessments of worth and in which money equals security and power, equal right to pleasure will likely remain unrealized without equal pay.

The reporting in this book is great. I'm curious what surprised you the most after talking to over one hundred mostly straight women about their sex lives?

I was surprised by the extent to which I encountered two particular sentiments. The first was women assuming a default second-class position in their intimate relationships. This showed up in faking it, in grudging intimacy, and in viewing sex as a kind of chore or duty, or as something to hurry through and be done with. But it also showed up in women's tendency to regard sex in rather male-centric terms: that is, as an act that revolves around penetration, that begins with male arousal and ends with male orgasm. If this is how women are approaching eroticism, it's not surprising that so many report dissatisfaction, which links to the second point.

A number of the women I spoke with were on distant terms with their own desire. They did not know what they really wanted. They had never been encouraged or granted themselves permission to inquire into the shape and object of their own desires. So they settled for what they thought they were supposed to crave and enjoy — i.e., a monogamous partner and regular penetrative sex --while quietly condemning themselves for not actually craving or enjoying those things.

On the flip side, for women who really inhabited their sexuality and were fluent in their own eroticism, sex was not about particular acts or positions or any of the mechanics of bedroom life. It was about exploring the depths of their imaginations and opening themselves to the possibility that desires change, that desires are often a far cry from polite yearnings, and that desires are rarely politically correct. The women who most enjoyed their sex lives were also willing, I'd say, to step into the discomfort between what they actually wanted and what they thought they should. To do this, though, really requires that women feel safe and empowered in their own expression.

I found it interesting how you talk about how many women in heterosexual relationships think it's the responsibility of a man to give them sexual pleasure. I think in a way we are taught that from an early age. What, in your opinion, could change about how we learn about sex from a young age that could empower women to take responsibility for their own sexual pleasure?

The way that young people learn about sex — if indeed they're lucky enough to actually learn about sex in this country — tends to support the idea that men and women are very different animals. While sex ed curricula are likely to go into the biology and mechanics of male arousal and ejaculate — presenting these as natural phenomena because they're necessary to the continuation of the species — there is rarely any corollary discussion of female desire or arousal; female sexuality is presented in terms contoured mainly by reproduction or risk. Furthermore, young people learn about the vagina as the female sex organ, and correlate to the penis. Far less frequently do they learn about the clitoris, whose sole function is providing pleasure to its owner.

Basic amendments to the way we present human sexuality and anatomy would go a long way towards empowering women and helping both women and men approach sexuality as a mutually gratifying exchange.

What do you think needs to change about how society approaches trying to "fix" a woman's low libido?

The market for fixing women's libido is really booming these days, and that is positive in some respects: it does suggest that women's desire is being seen as a legitimate issue and that women deserve to feel more and want more. But on the other hand, the way the market is structured tends to mirror all the other ways women are relentlessly told that they need to change and aspire to ever better versions of themselves. I think, overwhelmingly, the market offerings, from books, to workshops, to online tutorials, to pills, and creams, and even surgeries, extend the notion that women, as a class, are essentially improvement projects. They should never drop their guard, they should always gaze upon themselves with a critically appraising eye. Am I too fat, too thin, too sad, too disinterested, too horny? Do I like sex enough. Good god, am I having enough of it? And in the realm of libido and sexuality the impulse to insistently tweak and improve gets portaged a bit deeper into women's bodies and psyches.

As I said before, chances are there's nothing "wrong" with a woman's libido. Rather, it's her circumstances that warrant some improvement — whether that's getting help with the household division of labor, or helping her partner learn to really listen when she's expressing what she wants. So I think the first step here is chucking the idea that women's libido should be fixed at all. If she deems it low, that's probably a symptom of other matters being awry.

The sex industry, like porn and sex-adjacent services, is still so such a man's world. Do you think that will ever be able to change? And if so, do you think women would benefit if it was more inclusive?

There is a growing volume of porn and erotica produced by women. Some of it is explicitly feminist or at least tries deliberately to challenge crude, violent and wearied tropes, but some of it is just more violent material produced by women. I think that for women who enjoy porn and erotica it would be hugely beneficial to have more offerings available, so that they're not masturbating, like so many men are, to really repetitive scenes of their own objectification. But I also think we're overdue for a bold reimagining of the genre, to take it beyond closeups of plumbing and incorporate a wider range of imagination, which is where eroticism resides.

Shares