Do you recall the various literary controversies that occurred earlier this year? No? It was fairly recent, yet it feels like a lifetime ago. That’s how much our collective minds have been consumed by the global pandemic that has changed the world forever. Nevertheless, if you’re looking for some reading material to get your mind off our stressful reality or to work through it, April has plenty of new releases on offer. Plus, since many of these authors have had to cancel their book tours, buying books now is a great way to continue to support the literary community.

Highly anticipated is the insight that Madeleine Albright’s “Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir” (Harper, April 14) will impart as she weaves geopolitics in with narratives of her own life. Also in the non-fiction category is something that may help us deal with our transition to working at home, organization guru Marie Kondo’s latest guide, “Joy at Work” (Little, Brown Spark, April 7), which offers at advice for how to declutter our workspaces and not become overwhelmed. And then there’s “Invisibilia” podcast host Lulu Miller’s book “Why Fish Don’t Exist” (Simon & Schuster, April 14) which may not initially seem relevant to our current situation, but does in a roundabout way. Miller examines the story of American taxonomist and ichthyologist David Starr Jordan who doesn’t give up when his life work discovering and collecting fish is destroyed in an instant in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Today, Oprah’s Book Club announced their April pick, Robert Kolker’s “Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family,” a deep dive into the story of the Galvins, one of the first families to be studied by the National Institute of Mental Health, shedding light on how the study, diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia developed in the second half of the 20th century.

On the fiction side, veterans Anne Tyler, the late Madeleine L’Engle, and Sue Monk Kidd all have new books out. “Redhead by the Side of the Road” (Knopf, April 7) is the Pulitzer Prize winner’s latest about a middle-aged man whose stable, regimented life is thrown for a loop by his lover and a possible lovechild from his college days. As for L’Engle, the “Wrinkle in Time” author’s posthumous “The Moment of Tenderness” (Grand Central Publishing, April 21) is a collection of 18 short stories, many of which haven’t been published before, that span genres from science fiction to fantasy. And Kidd’s fourth work of fiction, “The Book of Longings” (Viking, April 21) is a hefty tome to dig into about Ana, a woman who marries a young Jesus, long before his ministry.

In contrast, April also showers us with a number of debuts. C. Pam Zhang’s novel “How Much of These Hills Is Gold” (Riverhead, April 7) is an epic adventure story set in the Old West, told from the point of view of two Chinese American orphans in the wake of their father’s death. Afia Atakora also makes her debut with “Conjure Women” (Random House, April 7), a novel set in the American South before and after the Civil War, in which three women who heal must go through great lengths to save those they love along with themselves. Cho Nam-Joo’s first novel and international bestseller “Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982” (Liveright, April 14) has already launched Korea’s new feminist movement with a tale about the titular protagonist who confides in a therapist about the discrimination and hopelessness she experiences from the heavy expectations placed on her gender.

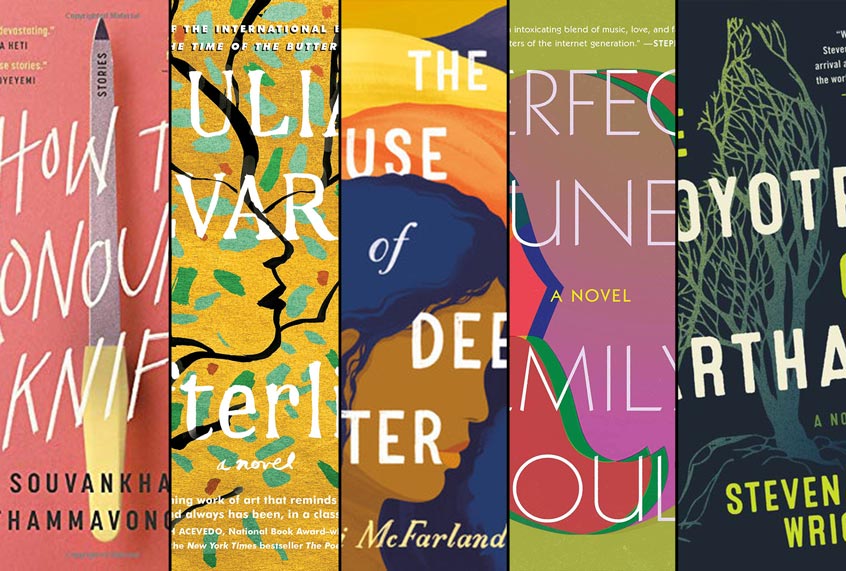

In addition to these books, Salon’s writers also highlighted five more must-read new books coming out this month below.

“Afterlife” by Julia Alvarez (Algonquin Books, April 7)

Acclaimed poet, novelist, and essayist Julia Alvarez is back to tell the tale of Antonia, a 65-year-old retired literature professor, in the year after her husband Sam’s unexpected death. Although she’s somewhat moved on with her life, she can’t but help see every moment through the lens of what Sam would say, what he would do in certain situations. Amidst this grief, however, life goes on, and she’s suddenly confronted with two challenging situations: her older sister Izzy has gone missing, and an undocumented pregnant teenage girl shows up at her home with nowhere else to go.

Fans of Alvarez’s previous acclaimed novels “In the Time of the Butterflies” and “How the García Girls Lost Their Accents,” will recognize her hallmarks in “Afterlife“: a story informed by her childhood in the Dominican Republic and growing up as one of four sisters. Here, however, Antonia and her siblings have been fully assimilated into American life, some with husbands or jobs as therapists.

Nevertheless, those roots and feeling of Otherness continue to be felt throughout the novel in Antonia’s reluctant assistance of the undocumented Mexican workers in her Vermont town. Skillfully executed, “Afterlife” is more muted than her other novels, yet still is a compassionately political look at how we view the workers whom we gladly exploit, the immigration crisis, what we owe ourselves, and what we owe each other as a community.

Alvarez also layers into this narrative an examination of individual purpose, mental health, grief, and where all of these belong in the grand scheme of life where one person’s tragedy can exist concurrently with another’s humdrum existence. Without citing it, Alvarez refers often to W.H. Auden’s poem “Musee des Beaux Arts” that digs into this “life goes on unawares” theme, observing how in Pieter Brueghel painting “The Fall of Icarus,”

. . . the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Despite these serious themes, Alvarez’s insight into human nature and cultural stereotypes lends a lightness and sense of hope to the novel, as does her playful analysis of the phrases used in everyday American speech and how the sisters deploy them. The latter displays Alvarez’s poetic hyperawareness of lyricism and word choice, and her ability to create moments that are simultaneously poignant and hilarious showcase this mastery. “Afterlife” questions the glib, inspirational sayings that we as a society trot out to make sense of tragedy and injustice, and offers comfort in the universal experience of how we’re all working it out as we go along. – Hanh Nguyen

* * *

“Perfect Tunes” by Emily Gould (Avid Reader Press, April 14)

Laura and Callie have the kind of friendship that in mid-life is hard to explain to anyone who wasn’t there in the beginning: Callie is the preternaturally beautiful, successful singer, while Laura — underslept, hassled, her musical talent mostly dormant under the weight of life — teaches music to other people’s kids while raising her own, first as a single mom and then as half of a blended family. But at the turn of the millennium, they were best friends — one quirky, one glam — reunited in New York after college, whose underwhelming jobs provide a mere backdrop for the main event: late nights flirting with early-career musicians, and the possibility of Laura’s career taking off via a band they threw together called the Groupies. This is why Laura came to New York in the first place, after all: “to live the kind of life that she could write songs about,” Emily Gould writes in her engaging and insightful second novel “Perfect Tunes,” a forthright exploration of friendship, motherhood and the contradictory joys and perils of the creative life, that’s also a refreshing women-focused alternative to all those stories I’ve read about men’s terribly important, tragically artistic lives and their devastating inability to commit to anyone other than themselves, or whatever.

Even though the East Village wasn’t quite what she thought it would be in 2001— “rents were higher, people died far less often, and there were stores that specialized only in Japanese toys” — Laura is still in love with her new life, her neighborhood, and all of its possibilities. And she’s infatuated with Dylan, a moody, talented guitarist with an intoxicating effect on others. But when she’s left to raise a daughter on her own, Laura watches from the sidelines as Callie’s star as a performer rises while her own unique sound gets buried under years of animal cracker dust and the grinding ecstasies and tedium of parenting Marie. Then her daughter’s teenage quest to learn more about her father pulls her away right at the moment when Callie presents Laura with an opportunity to resurrect her own mythical younger self, if she can.

To Callie, there’s no reason why Laura can’t pick up where she’s left off with her music any time she wants. The motherhood divide in female friendships, real and fictional, can be painful, and for some it proves impossible to navigate. But Gould doesn’t demonize or caricature unencumbered Callie, nor does she romanticize Laura’s sacrifices. Callie is living the life Laura thought would be hers, but she also tries to push Laura toward her own version of it as much as she can. Callie’s inability to get the mom life also means she doesn’t automatically relegate Laura to it. “Perfect Tunes” has a lot to say about the complexities of motherhood, but it’s also an argument in favor of keeping in touch with at least one person who really knew you when you were young. —Erin Keane

* * *

“The Coyotes of Carthage” by Steven Wright (Ecco Press, April 14)

In Steven Wright’s darkly funny and bleakly honest debut novel about how elections are bought, we meet Dre Ross, a senior associate in a cutthroat K Street firm, in mid-freefall. His fiancée has left him, his brother is dying, his drinking is escalating, and his mentor has given him one last chance after a major screw-up to save his job by completing the worst assignment ever: convince the people of insular and evangelical Carthage County, South Carolina, to vote for a resolution that will allow a precious metals conglomerate to buy a coveted parcel of protected public land that generations of local hunters have enjoyed. Turns out there’s gold in the Carthage County hills. Dre has a quarter of a million in dark money, his mentor’s green grandson as an intern, a ramshackle campaign headquarters, meddling local contacts, the impossible task of flying under the radar as a black man in a very white rural area, and no choice but to make this work. The Carthage County campaign is a low one, beneath his skills, but it’s all he has. Dre skids into Carthage County on professional and personal fumes, where he has to confront his own long-buried anger and grief or be destroyed by it.

Wright, the co-director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project who served as a Justice Department trial attorney during the Obama administration, has created a compelling fish out of water in Dre — a former teen con artist caught between his past and his present, the main difference being his much higher-stakes con on democracy is legal. He can’t control his handpicked straw man Tyler, and when given the opportunity to nurture an earnest if ethically conflicted mentee in Intern Brendan, he botches that too. His first hint of salvation comes courtesy of Chalene — doting wife to Tyler and mother of their many, many boys — whose hidden talents emerge after a campaign setback.

In Chalene, who turns out to be far from the People of Walmart caricature she’s assumed to be, Dre meets his match. Has he created a monster or discovered a rising star? When faceless corporations are footing the bill to undermine the electoral process in the name of liberty, collateral damage be damned, does it even matter? Contrary to popular opinion, our democracy hasn’t gotten close to hitting rock bottom yet. And until it does, Wright’s cautionary tale warns, don’t expect Americans to make meaningful moves to save it. — E.K.

* * *

“The House of Deep Water” by Jeni McFarland (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, April 21)

Linda Williams’ life seems to be marked by choices she’s made that still somehow leave her grasping for control. Some of these choices are considered — like when she leaves her deeply fractured marriage — and some are more impulsive, like when she subsequently strikes up an affair with Ernest, an elderly womanizer who has managed to stay on the seductive prowl despite his faltering health. Combined, these choices leave her in her early 30s, pregnant and living back in the hometown where she vowed she’d never return.

River Bend, Michigan, is the kind of small town where people monitor the comings and goings of their neighbors by unconsciously committing the sounds of their individual truck engines to memory. On the surface, it’s idyllic, “perched just above the state line in the soft crook of the St. Gerard River,” but scratch that surface just slightly, and generations of racism, misogyny and tangled familial secrets and abuse are thrust into the daylight.

“River Bend is full of men who want to take and take. Just last June, that horrible man Gilmer was caught hurting children in his basement,” one foreshadowing passage reads. It’s not a place where women thrive, so women “especially those of limited means, must learn to read the signs.” Despite all this, it’s the kind of small town that manages to dig its claws into you, even if you manage to leave.

And Linda isn’t the only one who has been called back to River Bend. There’s Beth DeWitt, Ernest’s daughter, one of the only black women to come out of (and leave) the town, and Linda’s former babysitter; she’s now a single mother of two who is retreating from a divorce of her own. And then there’s Paula, Linda’s mother, who abandoned River Bend, and her still-besotted husband, long ago.

And somehow, they all end up living under Ernest’s roof; it sounds far-fetched, sure, but the way it happens is all too believable and, as you can imagine, deeply uncomfortable.

The close proximity of the women and their lovers — both new and old — wears away at any facades they’ve individually constructed, which also reveals a greater River Bend truism: this is a community where everyone thinks the worst of each other, while simultaneously hoping the people around them think the best of them.

In McFarland’s debut novel, she parses out what overcoming that prejudice means for the characters’ futures, and if that’s enough to even start healing a community bogged down by macroaggressions and abuse. Some descriptive sections lag, especially in comparison to the emotional thrust of McFarland’s dialogue, but in the end “The House on Deep Water” is a nuanced, realistic portrait of small-town America, brimming with secrets and scandal. – Ashlie D. Stevens

* * *

“How to Pronounce Knife” by Souvankham Thammavongsa (Little, Brown and Company, April 21)

The image on the cover this collection of short stories requires a second glance. Long and pointed at one end, it is not the expected knife from the title, but a nail file, inspired by the story “Mani-Pedi” in which a former prize fighter finds a new life working at his sister’s nail salon. It’s a story of starting over from the beginning, learning a new language and culture, understanding that one is lucky to be alive, laboring to fulfill another’s desire. It’s an encapsulation of not just the immigrant experience, but the refugee experience.

Souvankham Thammavongsa delivers her 14 stories about the Lao experience in America with a no-nonsense attitude and blunt language, laying bare the practical, often briskly unsentimental viewpoint of protagonists who assimilate in a world that chooses only to see them as people whose backs are useful to step on to reach the next goal. For the reader, witnessing such treatment can be both aggravating and heartbreaking, but for the characters themselves, they face these indignities and move on because that means survival.

From the books’ title, there’s the young girl who mispronounces “knife” in class because that’s how her father sounds it out. Another story takes one mother’s love of Randy Travis to extremes, while another examines what happens when a teenage girl who picks worms out of the ground finds a boy at school who wants to do the same. In “Chick-a-Chee,” two young boys discover a delightful way of scoring chips and sweets from the wealthy.

While most of the stories deal with a struggle to live while making ends meet, some merely use menial jobs as a backdrop to observe the human condition play out. But most of the characters are trying to navigate culture, idioms and relationships to find a place or connection in the world.

The stories aren’t just unsentimental, but rather unromantic as well. Those who dare to brush against love and romance tend not to see clearly, and are often viewed with condescension. In fact, romantic abandonment is met with fierce independence and unexpected sangfroid. This is the practical price of fleeing a country with their lives; and to complain about love lost is to understand that one at least had the luxury of love.

Tinged with melancholy, anger, and a healthy dose of dark humor, all of these stories exhibit a fierce pride in what one can accomplish. After leaving everything behind and dealing with a country that does not cater to you, one can still celebrate the resilience of the human spirit by merely surviving. – H.N.