The world is in the middle of a pandemic.

As of March 26th, the US surpassed China as the country with the most COVID-19 cases and is now the new epicenter of the outbreak. And yet, there are still people and organizations going about as though everything were normal, or insisting that measures to control the virus are an overreaction. This insistence in pretending that everything is normal will only make things worse.

The world is in this situation because many countries across the globe did not react quickly enough and did not take the threat seriously. This becomes clear when comparing those countries that reacted rapidly, including South Korea and Taiwan, to those that tried to ignore the virus or insist that it was not their problem, including the US and the UK. As a result, the entire world is in a position of lasting consequences for populations, health systems, and economies.

Nevertheless, the situation can still be improved. Even now, quick science-informed action can help to mitigate the damage — improving testing capacity and efficiency, rapid identification and isolation of cases, strong measures of social distancing, and clear communication and transparency from governments and health systems.

The US and South Korea detected their first cases on the same day, but the responses were very different, particularly in virus testing. As of March 24th, Korea had tested around 300,000 people out of a population of about 51 million, or about 1 in 170 people — including many with mild or no symptoms — while the US had only tested about 1 person per 1,090. Tests remain difficult to obtainin the US, even for those with symptoms.

Korea greatly slowed its epidemic without locking down entire cities. "South Korea is a democratic republic, we feel a lockdown is not a reasonable choice," says Kim Woo-Joo, an infectious disease specialist at Korea University, in an interview with Science. Korea also tested widely, introduced strict social distancing, and monitored citizens extensively while maintaining widespread education and transparency of information.

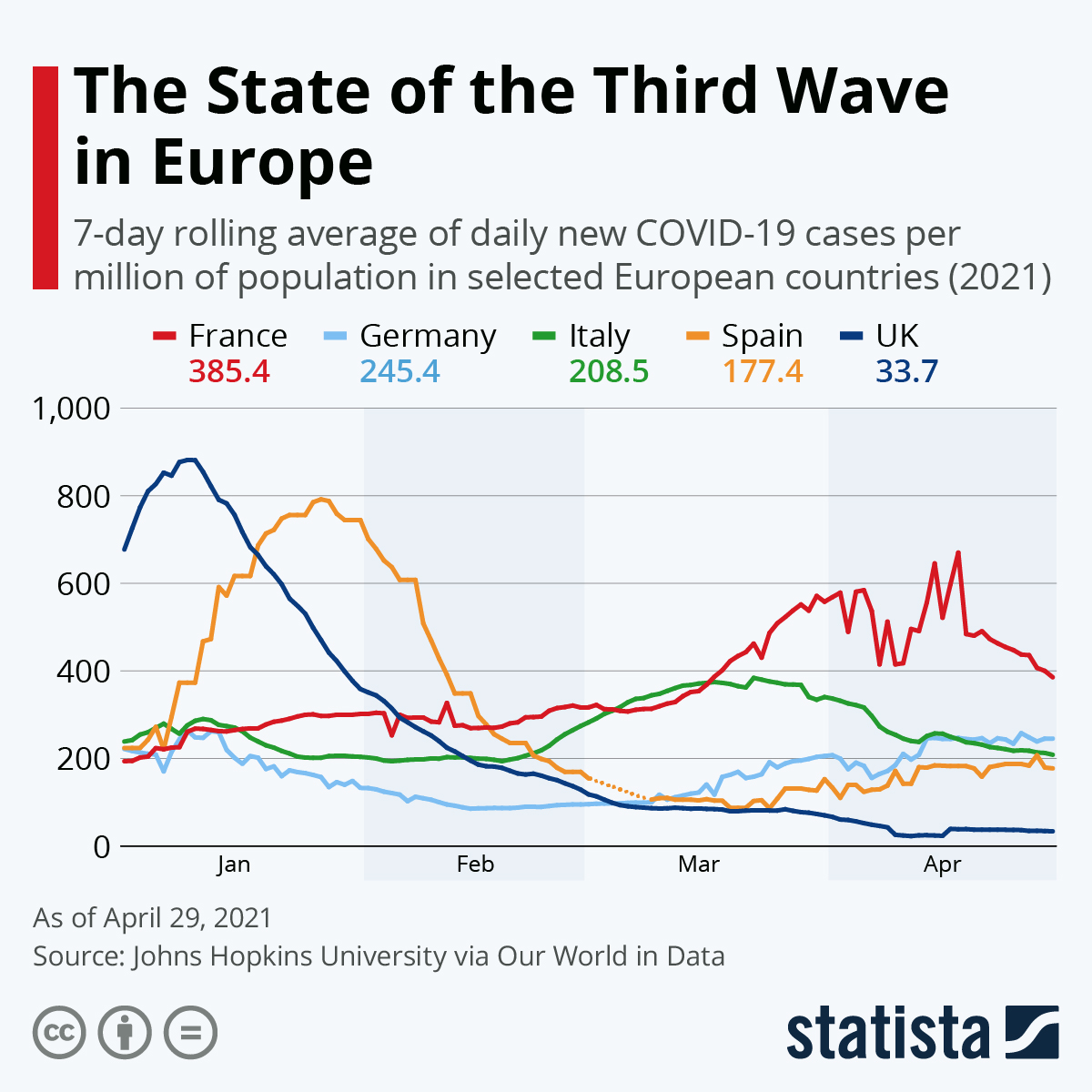

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

They had learned valuable lessons from earlier coronavirus outbreaks, including the outbreak of SARS in 2003 and a 2015 outbreak of MERS. For example, South Korea set up daily announcements providing detailed description of the extent of the outbreak in the country starting in January. In early March, US President Donald Trump was still making misleading comparisons to the seasonal influenza on Twitter, neglecting knowledge that COVID-19 would be much worse. While the CDC sent US households a small card, with only one side containing minimal information about avoiding infection, and the other announcing "PRESIDENT TRUMP'S CORONAVIRUS GUIDELINES FOR AMERICA," South Korea has released extensive data, allowing the creation of detailed outbreak maps (though there are also concerns that the government is disclosing individual data in too much detail, threatening citizen privacy).

Trump-branded mailer for coronavirus response guidelines. (Credit: Dan Samorodnitsky)

On the other side of the spectrum, the UK was also slow to react, at first suggesting that the virus be allowed to sweep across the country to establish "herd immunity" no matter the toll. This strategy proved untenable and immoral and it has since been discarded. But the poor response has led to widespread infection in the UK, including positive tests for Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Prince Charles.

The failures in testing for COVID-19 in the US continue to make it impossible to know how widespread infection actually is. Messaging from state and federal governments has been confusing and inconsistent, and social distancing was not implemented quickly enough nor in a systematic manner across the country. There was extended focus on restricting movement in certain regions without an understanding that the virus had already spread beyond those hotspots. For example, there was evidence that the virus was spreading "under the radar" in Seattle, Washington as early as late February, but the Federal Government did not declare a disaster and release federal emergency funding for that state until March 22nd. Trump recently voiced a fleeting plan to declare a quarantine around New York and adjacent states, even though the virus by then had already been spreading throughout the country. Finally, there was an intense focus on the risk to older individuals without enough acknowledgement that the true dimensions of vulnerability are not yet fully known. CDC data from March showed that nearly 40 percent of patients sick enough to be hospitalized were age 20 to 54.

The New York City area has emerged as an outbreak epicenter within the US, with almost 40,000 confirmed cases in the city alone by March 30th, and the full extent of the outbreak is still not known. The risk to the rest of the country has not received as much attention, but there are alarming indications that the entire country faces difficult times. Cases in Louisiana, for example, are increasing rapidly and the case fatality rate is at 4%, higher than anywhere else in the country. (US case fatality rates may change as testing becomes more widespread.) Rural areas of the US also have higher risk related to underlying health conditions that are likely to make infection worse, both as individuals and as specific social groups, including coal miners with lung diseases. Nationwide, areas where people are concentrated and cannot socially distance, such as prisons, immigration detention centers, and the homeless are also at extreme risk.

Now, the only choices are between bad and worse. The best choice is for social distancing to extend as far into the future as necessary. It is time for individuals in the US government to stop making false promises, like recent claims that the country could be back to normal by Easter even though that was never plausible. The US must be honest about resource constraints and areas of uncertainty, such as admitting that masks may have some practical use for healthy people, but that individuals at low risk should not use them in their daily lives because it would deprive front line health workers from a sorely needed and scarce resource. To do otherwise only breeds distrust and confusion. The US administration must begin to follow the instructions of public health experts in order to minimize the damage, since it is too late to contain the spread of the virus. Many legitimate warnings have gone unheeded, both from experiences in China and from US health experts.

The US must also make strong decisions that will help to protect its healthcare workers, who are already suffering from shortage of protective equipment and overwhelmed by the number of patients. A stronger system of sharing resources across the country, such as Spain's decision to nationalize private hospitals during the crisis, could help the entire country work efficiently as a whole. Setting aside political divisions and accepting more help from other countries could also help ease the burden on US health care providers, withChina offering supplies, and Cuba offering medical personnel to assist across the world. The US response must stop prioritizing the economic well-being of private companies over the well-being of the citizens. Low-cost ventilators designed with taxpayer money were sold to other countries rather than being stockpiled to be used in the US. The US has been catastrophically slow to use the Defense Production Act, which can compel private manufacturers to make ventilators to meet national need. Finally, the US must prepare for future outbreaks as soon as possible, including stockpiling medical equipment once this pandemic abates, and establishing efficient hospital procedures to further reduce the spread of disease to health care workers, which have been successfully used in Singapore.

With COVID-19 devastating high-income countries, the future of the pandemic for middle- and low-income countries is bleak. Leadership in some countries, including in Mexico and Brazil, continue to downplay the virus. India, with its large population and high rates of poverty, cannot establish the same social distancing protections that are possible in the US or Europe. Low income countries with limited healthcare capacity, including Uganda and Somalia, are bracing for a widespread crisis. Displaced persons and individuals in refugee camps and war zones are at extremely high risk due to the crowded and difficult conditions in which they live.

Though the picture is frightening, this does not mean that public health measures are useless. To the contrary, the combination of scientifically sound policy and transparency like what was achieved in South Korea, a focus on protecting health care providers and coordinating hospital resources, medical research, and a social system where people act responsibility for themselves and others, is the best way to emerge from the pandemic with the least possible damage. ![]()

Shares