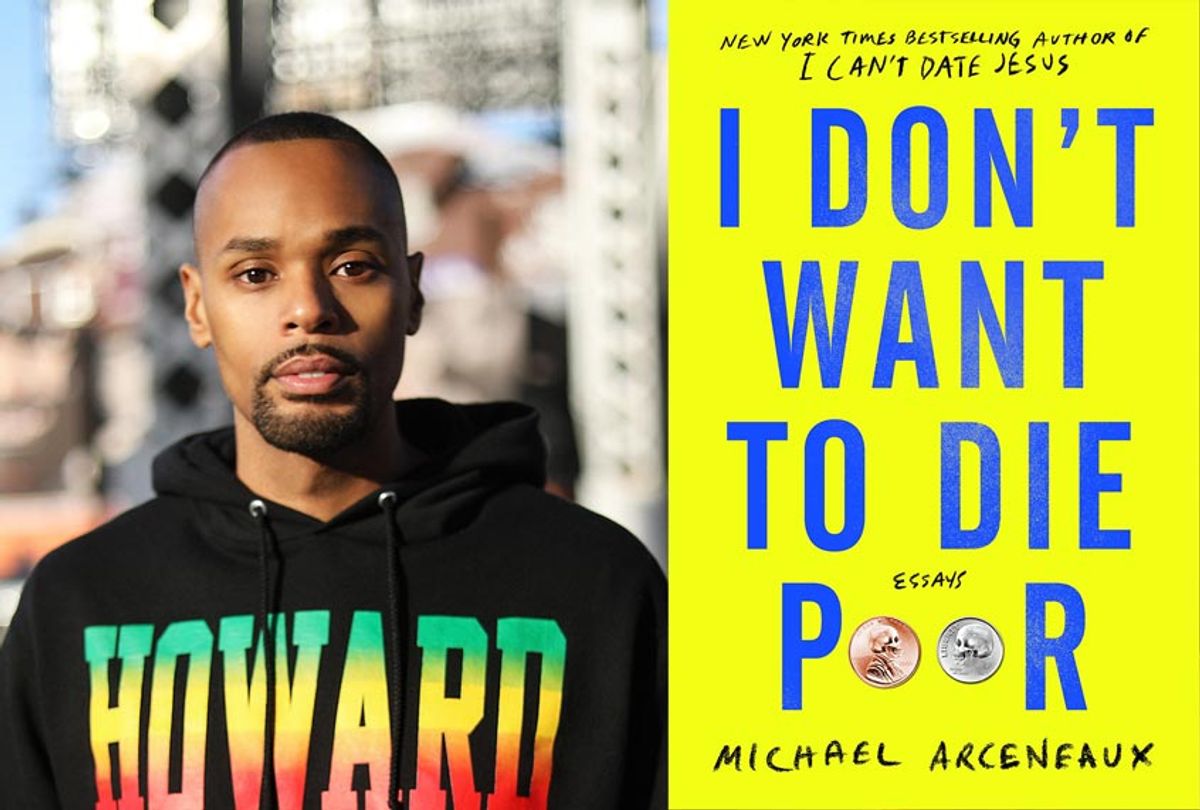

Even though Michael Arceneaux's second book "I Don't Want to Die Poor" was written before the pandemic, it could hardly be more relevant to present moment. As the economy takes a nosedive, with an estimated one in 10 Americans suddenly out of work, basic needs like food and rent money are suddenly out of reach for millions of Americans. Meanwhile, debt — mortgages, medical debt and student debt — are a vastly greater burden for many.

To Arceneaux, these kinds of struggles are familiar. "I didn't grow up with money, so I mean if you don't grow up with money, for the most part you don't want to die poor," he told Salon. Arceneaux merges his own experiences with poverty with facts to create a compelling picture of our socioeconomic situation. "A lot of people, no matter how much you earn, you're probably one or two checks away from poverty. . . . you just probably haven't admitted it," he added.

Arceneaux was economically prescient, even though he wrote the book for the world we lived in before. Working people in the United States suffered a crisis of poverty caused by loan debt and a lack of a social safety net, Arceneaux writes; the coronavirus pandemic only exacerbates that. In his new collection of essays, Arceneaux explains how debt affected every facet of his life. While the book takes on dark subjects, his humor allows for the reader to laugh at the chaos of it all with him.

We spoke with Arceneaux about the pandemic, student loans, and what it's like to promote a book during these odd times. As always, this interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How are you doing during this pandemic?

Every day I try to tell people [I'm] as well as I can be in a nightmare. I will say, last week, the gravity of everything kind of got to me. But I think for me, I've had a book to promote and so I've really needed to be focused. It's not a great thing to release a book in the middle of a nightmare, so I've been really focused. But I'm good as can be. It's just a lot on all of us.

Totally.

The sirens and the captivity are getting to me.

Are you in New York?

I'm in Harlem. I was actually planning to be moving, but it looks like I'm going to be here until I can go outside safely. Whenever that is.

Right? Who knows. So the title of your book is "I Don't Want To Die Poor." Have you always had this fear?

I didn't grow up with money, so I mean if you don't grow up with money, for the most part you don't want to die poor. I found out writing the book that a lot of people, no matter how much you earn, you're probably one or two checks away from poverty. You just probably haven't admitted it. But no, I think in terms of like, I don't want to die poor, the idea that I might actually really, really struggle, worsened by the time I graduated and the media, as I understood it, had already imploded. My fears kind of grew and then the great recession happened.

The title of the book is serious; it's full of serious topics — racial inequalities, class disparities — but you remain optimistic and humorous in it. Is maintaining a sense of humor a choice you make for you, or is it for your readers or both?

I don't say this in like an arrogant way, but while I'm mindful and grateful of my readership, I write what I feel. If you write to your reader, I don't know if that's a great idea. I think for me, at least with humor, it has kept me alive. Humor keeps a lot of people alive. I think even when my family, as complicated and as dark a history that all is, everybody in my family is incredibly funny. We have our own sense of humor or strong personalities. But I guess I think maybe the difference between book one ["I Can't Date Jesus"] and two ["I Don't Want to Die Poor"] is that in the second book I really allow myself to have those darker moments.

Sometimes I just kind of make a joke, even at the worst possible time, and then I get annoyed with myself. I can't help it. And so there were moments in there, like the takeaway that was there, but then I took them out because I thought, no, you just kind of need to let that be. But I think more often than not, if it's like natural to me and a joke comes out, I just kind of put it on the page. That's who I am.

Your writing is very funny. I did want to hear from you about how writing this book was different from your first one?

I mean, neither was an ideal experience, but the second book was a nightmare to write because I was in a place where I thought I wouldn't be at that point in my life, personally and professionally. So it was just really challenging. Also, I lost a lot of people last year, one after another for different reasons. But most of the reasons honestly tied to the kind of inequality I write about in the book. That was just a really hard time.

With this one though, I knew it was really important to write, but it was just really hard to write. It wasn't a good time. It was a lot darker material. It was a lot more revealing. So it was kind of just challenging throughout and I hated it. I can't say anything positive about the experience other than I like the book now that I'm so removed from it and it's out in the world.

I can't imagine writing a book while grappling with loss. How did you do that?

I smoked weed, like I mentioned in the book. I'll say this, last year was really, really difficult, but by the end of the year, I mean, I kind of knew that in my mind. I think I just got derailed in a lot of ways. Some things I just couldn't accept. I think for me what I'm finally trying to be better about is accepting things that I can't control, not just tolerating, but like really accepting. Kind of in the case of right now, this is again the worst time to be releasing a book. People are losing their jobs, unfortunately, so it's a big ask to be asking people to spend money particularly on a book that's about struggles.

It's just a bit of a mindfuck in and of itself. But again, this is my livelihood and I think what I came to accept is I'm doing the best that I can in everything that I do and whatever happens is kind of beyond my control. All I can control is how I react to it.

Your book is partially about the double-edged sword of student loans — namely, that they can quickly give you access to opportunity, but there's a high risk that they'll be a lifelong burden, especially when you pursue a career in an industry that's not financially lucrative. As you write, it's a bit of a trap. After writing and exploring all the ways that loan debt has affected your life, do you think it's still worth it?

It's hard for me to be like, "no, I wouldn't have done that." My life wouldn't be like it is now. I wouldn't be talking to you. Certain things wouldn't have happened. I think the problem is that I shouldn't — people like me should not have to go through all of that just to literally get basic access that everybody else can get. That's the bigger problem. Whether or not it's my individual choice. . . . I mean I could have still had a different, and I mean a happy life and full life, but it's not the life that I really would have wanted to pursue. So, it is what it is. I just wish I didn't have to deal with it.

Did it surprise you to realize how loan debt affected all areas of your life?

I am not really surprised. I don't come from money and I could see how that wore on my parents. I saw how that wore on everybody around me.

I guess I'm surprised that I opened up that much up about it. But I think also it's kind of really important. My book is very much about real economic anxiety. It's particularly from my perspective being black and gay from the South and all that. I think a lot of people who are used to being without, we kind of already know this, it's just whether or not we actually want to talk about it at length. I think that's maybe the surprising part.

Right. Well, I appreciated how open and honest you are about it. Not everyone is.

Thank you.

Especially when it comes to financial struggle, there's an ethos in American culture that "struggle" makes you "stronger." I think that is particularly used in regards to student loans, and student loan debt. The saying might be "there's beauty in the struggle." It's like, we are expected to struggle to succeed.

No, fuck that. No. I think for — if I were to lend myself to that awful sentiment, well-intentioned or not by people who would employ it, I would be feeding into the very type of shit that this book is against. I don't believe we live in a meritocracy. That is not how life works. Life is mostly about privilege, access and dumb luck. And then if you work and you're actually good at it, you might stay afloat. There's no beauty in my struggle. Again, I don't think I should have had to go through most of this. We all have our struggles, but they're, because there are well-off people who have struggled in their journey or whatever, but they had the means and the access to better treat it, to deal with it. That's the difference. I think inequality is inequality.

And the takeaway from this book is that it shouldn't be this way. Now, more than ever, literally people keep saying that this book is so timely now. And I know people mean that as a compliment, but the book was already timely before this. This is why everything is so much worse than it needs to be because we live in a society that will let us wither and die the minute we miss maybe like two checks and can't pay a bill.

Do you think inequality, particularly how it manifests financially, would look differently if we have the right politicians in place?

I write in the book about what Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — among other members of Congress — have done with respect to, but particularly those who are elevating the conversation around student loan debt. Though I have some specific issues with Joe Biden and his role in the 2015 bankruptcy bill that I reference in the book, and how it made it difficult for people with private loan debt. I could die right now and my mom would still be on the hook for my loans and I could not file bankruptcy and escape debt.

That said, I noticed that Biden has embraced — not completely Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders and stuff — but he's saying people with incomes up to $125,000, their debt can be forgiven if they went to a public school or if they went to a private HBCU (non-profit historically black colleges). [That] is very, very important because the reason why, even though it seems like a low percentage overall, black people are consistently being taken advantage of with private student loans because HBCUs [are] more often denied or not allocated the same amount of funds. We don't have as much money as white people by comparison, so we take on more debt. We don't get traditional forms of debt, so they prey on us. It's basically like the subprime mortgage crisis all over again. Just before it was impacted was impacting all of us. So I'm encouraged that even Joe Biden, of all people, is embracing this.

And I'll add, I think I'm for student loan debt cancellation, but the reality is based on the private loan that I wrote about, that 12 year plan, more likely than not, I'm not going to be forgiven anyway, but it's not about me. The wrong attitude too many people have is like, well, I had to pay my loans, so why don't you pay yours? No one should have to suffer the way you did. The whole point is to do better by the next generation, not let them repeat your mistake or in this case, be a recipient of the same level of exploitation.

Totally. What advice do you have for people who are really anxious right now about their financial situation?

There's nothing I can say off the bat, unless I can put money in your pocket. But I'll say this about . . . the bill aspect, and particularly loans, pay what you can pay and if you don't have it, you cannot stress yourself out to the point where you're harming yourself one way or the other. I know people are going to be worried about the damage to their credit and all that stuff, but I mean if it helps, we're already in a recession. That stuff is out of your control. It's not your fault that any of this happened. Stressing yourself out over stuff that you can't control will not help you anymore. You pay what you can pay and do whatever work you can find. You do whatever to keep yourself sane in the meanwhile and you do your best.

I hope that was helpful, but it's just hard because when people want money, they want money. I know when people worry about paying bills, it's just kind of like, you do the best that you can, whatever that is. And that's just going to have to be good enough until you can do better. But it's like, this is not our fault.

Shares