Maybe you are not part of the seemingly limitless population of stuck-at-home individuals relishing this sheltered time to start making sourdough, or order a pasta roller. Maybe you're indifferent to your friends' social media flexing on their photogenic feasts of humble "pantry staples." Have I got a girl for you.

"Some women, it is said, like to cook," author Peg Bracken cooly observed in the introduction to her 1960 bestseller. "This book is not for them." Instead, as Bracken put it, "This is for those of us who hate to, who have learned, through hard experience, that some activities become no less painful through repetition: childbearing, paying taxes, cooking." A full three years before Betty Friedan published "The Feminine Mystique," a working mother with a proudly acrimonious relationship to the kitchen unleashed "The I Hate to Cook Book," and made it cool to declare the process of getting food on the table a complete and utter bore.

Bracken was already a thriving copywriter and magazine contributor when she got the idea for a collection of recipes and household tips. The twist was that it would be culled not from the shared expertise of her female friends, a squad who called themselves "the Hags," but instead from their collective "ignorance" The world was already full of enough "big fat cookbooks;" Bracken wanted to tell a story about women, in particular those who "hate to cook but have to."

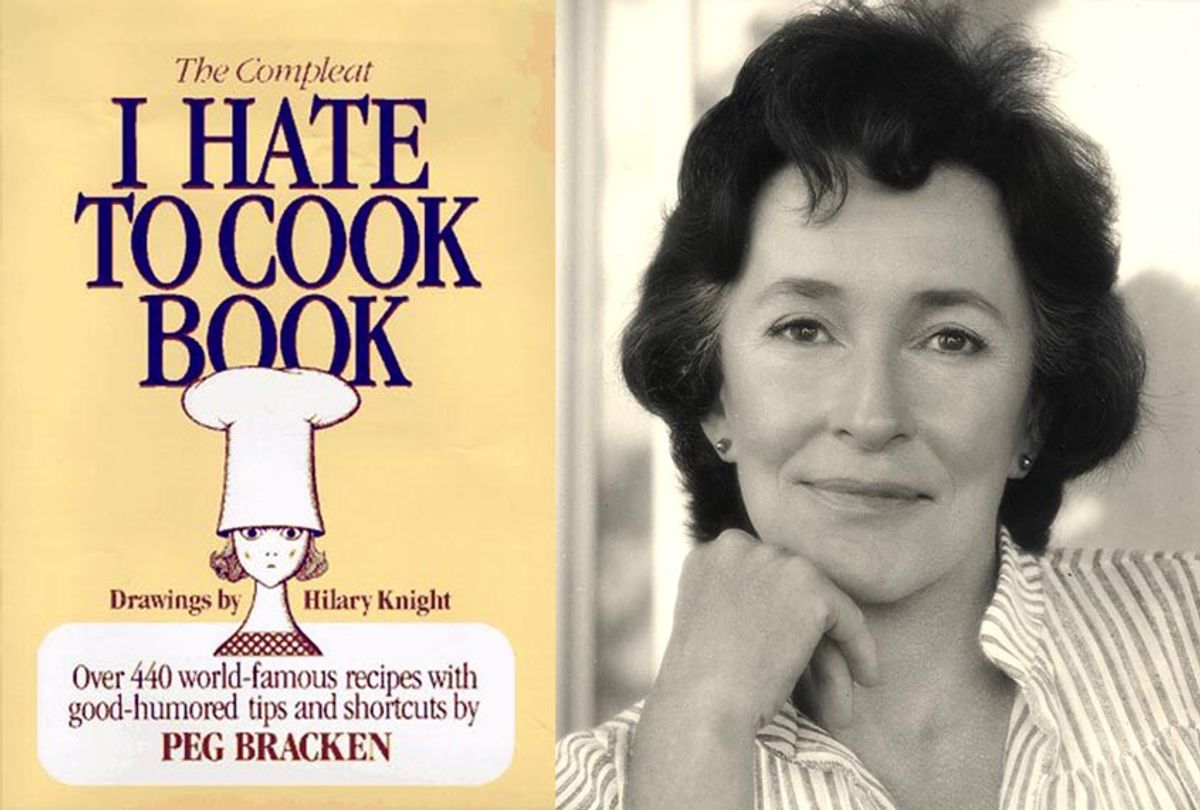

Six male editors rejected her proposal, informing her that "women regard cooking as sacred." Her own husband's assessment of the book was, "It stinks." But a female editor at Harcourt Brace picked it up. Fancifully illustrated by "Eloise" artist Hilary Knight, "The I Hate to Cook Book" sold three million copies. And it made Bracken a celebrity, the anti-domestic goddess of the "Mad Men" era.

I don't remember when I first discovered Bracken's writing decades later, only that she was part of a pool of saucy female columnists and commentators — along with Erma Bombeck, Nora Ephron, Molly Ivins — I fell in love with at a young age. Her words just clicked for me; Bracken's resigned but drily resentful depiction of domestic life seemed to echo the experience I had observed, night after night, dinner after endless dinner, in my childhood.

My grandmother, the chief chef of my home, never owned a cookbook, or consulted a recipe, for that matter. I can only assume she came to the I Hate to Cook philosophy naturally. By the time I was born, she had raised six kids and had meal preparation down to a science, if never an art. "It is understood that when you hate to cook, you buy already-prepared foods as often as you can," wrote Bracken, a statement that sounds like it could have originated equally from Jane Austen or my Nan. Likewise, Bracken's recipe for fruit salad is my grandmother's, nearly verbatim. "You peel and cut up some of whatever is available," she explained. "This isn't the Waldorf Astoria. Three is quite all right."

What Bracken masterfully articulated — a sentiment that feels refreshingly resonant right now, especially to the millions of women who've abruptly been punted to the role of school teacher, housekeeper, and three-meals-a-day-maker — was a subversive refusal to fake it. Just because one must answer the call of duty does not oblige one to enjoy it. It sure as hell doesn't impose an imperative to excel at it. "In the ordinary course of human events," she wrote, "there is no reason why you should ever have to cook a dessert." (As one who grew up on Chips Ahoys and Carvel cake for my birthday, I can confirm.) Even if you are somehow backed into a baking situation, Bracken insisted you at least make the best of it. Her recipe for Hootenholler Whiskey Quick Bread includes "¼ cup bourbon, plus more for you," and its first step is, "Take the bourbon out of the cupboard and have a small snort for medicinal purposes."

I was deep into my 20s before I even attempted cooking, having subsisted for years on ramen, Lean Cuisine entrees, and whatever I could mooch at various happy hours about town, which often meant dining on cocktail olives and lime wedges. Cooking, I assumed, was something wives and mothers did, ergo it was to be avoided at all costs. But once I started, I discovered to my surprise that I didn't hate to cook. I didn't even hate to bake. In fact, I loved it. Yet I know my joy of cooking was possible because I wasn't shoved into the kitchen, especially at the expense of my other interests and pursuits. In contrast, Bracken's daughter Jo has said that after her mother became a famous author, her father "was jealous… Her success made the marriage blow apart."

Until her death in 2007, Bracken parlayed her domesticity-averse image into other hit books, including the inevitable "I Hate to Keep House." She became a spokeswoman for Birds Eye, speaking to "people like me, who don't think it's a crime to cook easy if you cook good." And while her bar for "good" may look different to those who don't consider Lipton Onion Soup Mix the foundation of every meal, many of her humble standbys hold up just fine, like her chocolate Cockeyed Cake, a no egg or butter riff on a Depression era classic.

No doubt if she had been born in a different era, Bracken would currently have her own Food Network show and an endorsement deal with Dinnerly. More significantly, she'd be killing it on Instagram, using her inviting wit to remind every single person who needs to hear it that putting food on the table is not a competitive sport. And just like learning Portuguese or writing "King Lear," the goals we set for ourselves in this incredibly anxious, enraging, grief-riddled time don't have to be lofty, unpleasant, or against our talents and interests. Yes, these are more challenging times for people who always eat out. Yes, a baseline ability to feed oneself is required for survival, and competency in any field is handy. But that's about it.

Bracken's can of choice to crank open and call it a day was cream of mushroom; maybe yours is garbanzo beans. She was fine with fashioning dessert from a box of pudding mix spiked with sherry; maybe your thing is chocolate chips, straight out of the bag. No judgment! If "cooking" and "comfort" are not words you normally put together, this is not the time to start trying to make it happen. You can keep associating it with "hate" all day long. And if you're feeling isolated within this time of isolation, wondering why everybody is excited to make banana bread but you, take the words of Peg Bracken to heart. Sixty years ago, she reminded us that "The way to face the future is to take it as Alcoholics Anonymous does, one day at a time." And she made an offer to the reluctant cooks of the world that still stands, one of "a hands across the pantry feeling coming right through the ink," because, now more than ever, "It's is always nice to know you are not alone."

Shares