It turns out there is a good reason for reporters to attend Donald Trump's ridiculous, misinformation-spreading coronavirus news conferences.

It's to confront him with reality — and let him flail wildly, melt down and generally show the world he has no idea what he's done or what he's doing.

It's to ask him simple questions that any competent leader could easily answer, and watch him have a temper tantrum.

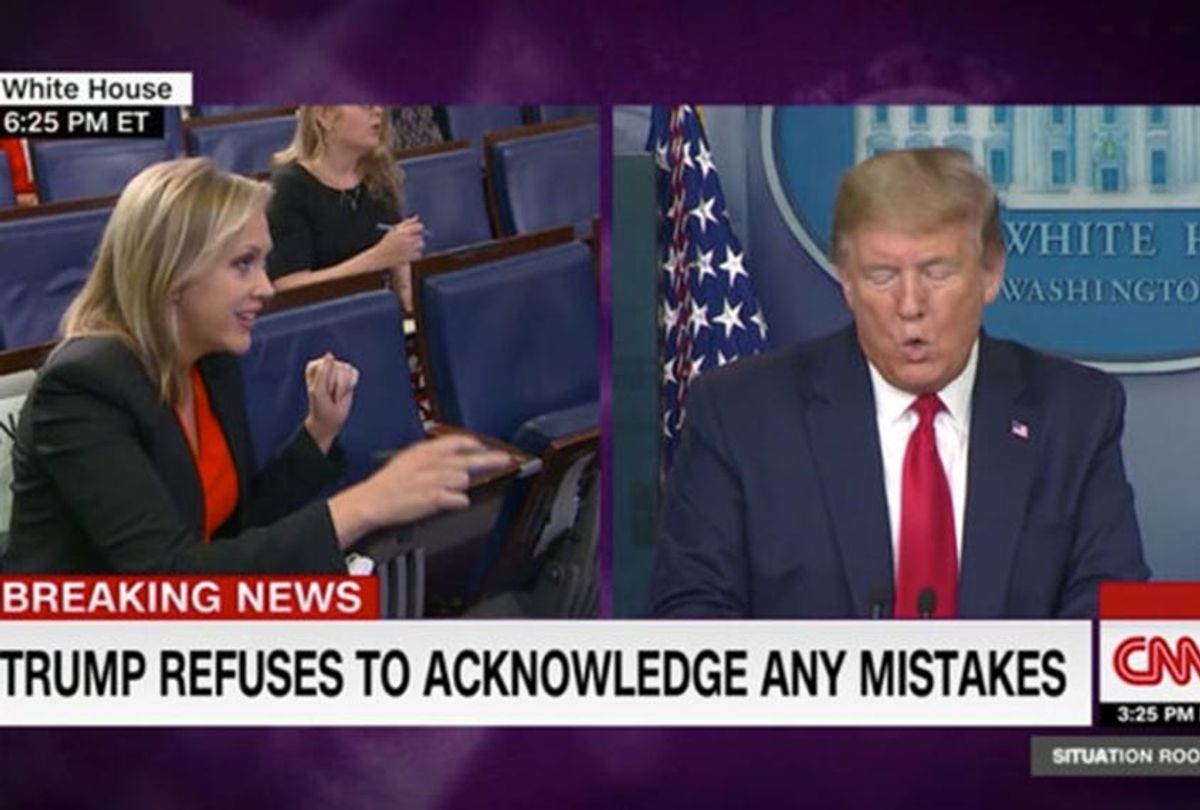

So here is part of Trump's exchange with CBS White House correspondent Paula Reid during Monday's session. (Watch the video):

Reid: What did you do with that time that you bought? The argument is that you bought yourself some time. You didn't use it to prepare hospitals. You didn't use it to ramp up testing. Right now, nearly 20 million people are unemployed.

Trump: You're so disgraceful. It's so disgraceful the way you say that….

Reid: Tens of thousands of Americans are dead. How is … this rant supposed to make people feel confident in an unprecedented crisis?… What did your administration do in February for the time that your travel ban bought you?

Trump: A lot.

Reid: What?

Trump: A lot, and in fact, we'll give you a list…. We did a lot. Look, look, you know you're a fake.

Here is part of an exchange with CNN White House correspondent Kaitlin Collins (watch the video):

Collins: You said when someone is president of the United States, their authority is total. That is not true. Who told you that?

Trump: You know what we're going to do? We're going to write up papers on this.

Collins: Has any governor agreed that you have the authority to decide when their states …

Trump: I haven't asked anybody because. … You know why? Because I don't have to ….

Collins: But who told you the president has the total authority?

Trump: Enough!

There were others, too. Like when Trump was asked what he would do if governors defied a presidential order to reopen their states — and it became clear that his talk about having "total authority" over everything was not a serious, considered assertion of extraconstitutional rights, it was just bluster. "Well, if some states refuse to open," he said, "I would like to see that person run for election."

To go or not to go

Not long after Trump started holding his almost daily news conferences, it became clear that they were not really about relating important information during a crisis, but were instead all about self-aggrandizement and the spreading of misinformation. Media critics and ethicists (including me) started arguing that television networks shouldn't broadcast them live.

(My theoretical, hopeful exception would be if a news organization were prepared to aggressively use a split screen to turn them into a vector for information instead of disinformation.)

(CNN's aggressive use of a chyron Monday evening was good for a laugh, but arguably only made things worse.)

The other question that came up was whether reporters from major news organizations should even continue to attend, knowing that Trump would just use them as props.

Jay Rosen, the NYU journalism professor and widely respected media critic, argued that serious news organizations should refuse to assist him in spreading misinformation — which means not sending anyone.

"I would not send reporters so he can waste our time and use them as hate objects. I would tell them to watch it on CSPAN and report any news that emerges. If he makes a factual claim it has to be verified or no go," Rosen tweeted last week.

And in his Pressthink blog on Sunday, Rosen published a list of 13 reasons that he thinks make reporters keep coming back for more. It is not an admirable list.

There's the simplistic view that whatever the president says is news, no matter what. There's the prestige of feeling like you're part of the presidency. There's the fact that it is such an easy and reliable way to create content. There's the overvaluing of access.

That's four. There are nine others, some better, some worse, and I highly recommend you go read them all.

But to my mind, Rosen left out the 14th — and only really good — reason for reporters to show up at the briefings.

It's this: They are the only people allowed in from outside the bubble.

Every president exists within a bubble, but some more intentionally than others. Trump — even more than George W. Bush, and that's saying something — will not be caught dead in a room with people who don't agree with him, with this one exception. He doesn't hold events that are open to the general public, only to supporters. He doesn't even invite Democrats to the signing of bills they collaborated on. And his bubble is exclusively occupied by loyalists and sycophants.

Reporters, once allowed inside the bubble, have enormous public-service responsibilities — particularly during a major public health crisis, and particularly with this president.

They alone can demand the answers the public needs and deserves. And they alone can confront him with the reality that he denies.

As the late, legendary White House press corps veteran Helen Thomas explained it to me in 2004: "The presidential news conference is the only forum in our society in which the president can be questioned. If he doesn't answer questions, there's no accountability.… We speak for the American people. We have a direct contact with the president of the United States and they don't."

At this moment in history, what the public needs more than anything else are answers to the forward-looking questions: What do we do now?

And with this president, confronting him with reality also means confronting him with the fact that he has no idea what he's talking about.

That's what Reid and Collins did so well on Monday.

But we need more.

Asking questions as a public service

The country needs a plan, and Trump doesn't have one. Reporters need to press him on that — in part to expose his lack of leadership, and in part to push him in the right direction.

The context here is that, in the consensus view of public health officials, there's a clear path out of this crisis — and Trump isn't taking it. What's required, first and foremost, is vastly more testing so public health officials can determine what communities are safe, and can identify outbreaks when they are still small and isolate the people who are infected.

So here's a question for Trump: Once we've reduced the number of infected people, don't you realize that it's not safe just to go back to normal until we can identify the people who are infected, make sure they're isolated and track down their contacts? Don't you realize that requires massively more testing than we're doing now?

There are at least three, widely-endorsed roadmaps from public health officials, complete with detailed, point-by-point plans for how to reopen the country and end the crisis safely. Ask him about those point by point: Do you agree? Disagree? What are you doing about it?

By contrast, the public service mission is no justification for stupid, incremental questions or attempted gotchas aimed at generating tiny little news scooplets. Those scooplets have no public-service value whatsoever.

What does this accomplish?

Better questioning won't change the essential nature of the event. As Lou Cannon, who covered the Reagan White House for the Washington Post, told me back in 2004, "News conferences have always been a forum for the president to say what he wants to say, not for us to get the information that we want to get."

No president has ever been quite this brazen about ignoring the substance of a question, or attacking the reporter who asked it. With Trump behind the podium, these news conferences will always be full of self-aggrandizement and misinformation.

(So Rosen may be right that no matter how excellent, thoughtful and tough the questions are, the net effect is still so bad that journalists should have no part of it.)

But only a tiny fraction of the news audience actually watches the briefings themselves.

So what matters more is how they are covered. And the coverage remains ridiculously variable — by publication, by reporters and sometimes even by day.

And even after Monday's epic meltdown — complete with a propaganda video — some reporters still couldn't shake themselves loose from old habits that just don't serve the readers anymore.

The New York Times news analysis by Peter Baker and Maggie Haberman ran under a headline that didn't just fail to capture the reality of the event, it actively covered it up: "Trump Leaps to Call Shots on Reopening Nation, Setting Up Standoff With Governors."

Baker and Haberman took Trump's comments seriously, rather than calling out what a farce the entire briefing was, and focused on how those comments raised "profound constitutional questions about the real extent of his powers."

The Associated Press' main story, by Jill Colvin, Zeke Miller and Geoff Mulvihill, played it straight. While in a separate story, Miller and Kevin Freking noted that Trump's use of "a taxpayer-funded promotional video praising his own handling of the coronavirus outbreak and slamming his critics and the press" was "a highly unusual move."

They cited a few particularly evocative Trump quotes — "Everything we did was right," and "I think I've educated a lot of people as to the press" — and concluded that the briefing "amounted to a telling demonstration of the president's growing defensiveness in the face of criticism that the administration should have acted more aggressively and sooner to combat the virus."

The lead story in Tuesday's Washington Post treated Trump's comments as if they came during a normal press briefing. The article by Tim Craig and Brady Dennis blandly reported on Trump's declarations of authority without giving readers any indication of the circumstances.

That task was left to Ashley Parker, writing under a marvelous headline — "The Me President: Trump uses pandemic briefing to focus on himself" — and a warning label that her piece included "a reporter's insights."

Parker wrote that Trump "made clear that the paramount concern for Trump is Trump — his self-image, his media coverage, his supplicants and his opponents, both real and imagined." And she wrote that "Monday's coronavirus briefing offered a particularly stark portrait of a president seeming unable to grasp the magnitude of the crisis — and saying little to address the suffering across the country he was elected to lead."

Post opinion writer Greg Sargent also contributed his analysis, which included this memorable line:

When everything is all about maintaining appearances, with no concern whatsoever for underlying substance, this seeming contradiction disappears in a puff of Trumpian chaos pixie dust.

Few American news editors give their reporters the freedom that David Smith, Washington bureau chief for the Guardian, gets to call it as he sees it. He wrote:

A toddler threw a self-pitying tantrum on live television on Monday night. Unfortunately he was 73 years old, wearing a long red tie and running the world's most powerful country.

Donald Trump, starved of campaign rallies, Mar-a-Lago weekends and golf, and goaded by a bombshell newspaper report, couldn't take it any more. Years of accreted grievance and resentment towards the media came gushing out in a torrent. He ranted, he raved, he melted down and he blew up the internet with one of the most jaw-dropping performances of his presidency.

Reporters should keep going to these briefings. They should use their questions exclusively to demand answers on the public's behalf and confront Trump with the reality he is incapable of accepting.

And then news organizations should recognize that the the news is not what Trump says — he'll say anything. It's what he fails to say, to do and to be.

Shares