Finger-pointing is maybe Donald Trump’s best thing.

So asking him unspecific questions about why the country isn’t doing more coronavirus testing is just an invitation to disinformation and blame-shifting. (Salon’s Amanda Marcotte offered a useful answer to that question on Wednesday.)

But the lack of testing has been the singular failure of his administration, from the very beginning of the crisis — when aggressive testing and tracing might have made a national lockdown unnecessary — to the present day, when the continued absence of a massive federal effort to test means that back-to-work orders will be tantamount to death sentences for many.

Public health experts are essentially unanimous that the current level of testing needs to be increased, not just a bit but by several orders of magnitude — perhaps many — before it’s safe for people to emerge from their homes. The only institution capable of the kind of industry-goosing and supply-chain management needed to achieve that is the federal government.

Rather than do something about it, Trump has alternately denied there’s a problem, blamed it on the governors, said he’s doing everything perfectly and denied any responsibility for anything.

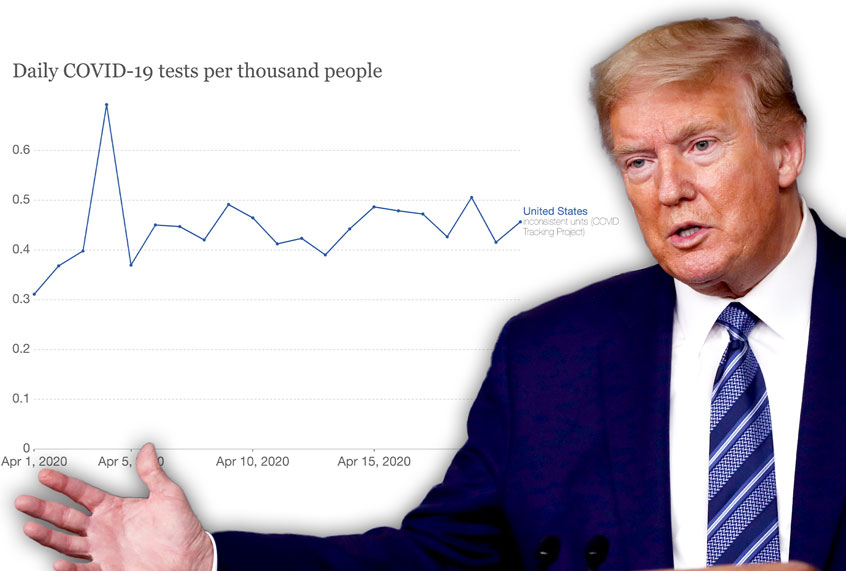

Meanwhile, due to a chronic lack of availability, and despite White House spin, testing numbers are not going up. They are flat. They’ve been flat pretty much all of April, averaging just under 150,000 a day.

Every day without more testing is another wasted day.

Reporters at Trump’s press briefings are the only people representing the general public allowed anywhere near him, so they have a responsibility to make him face up to reality. Instead of asking inane, easily gamed questions, they need to tell him specifically what the public health experts say he needs to do, and then demand to know why he’s not doing it.

They probably shouldn’t expect anything valuable in response — just more lies and insults. But specific questions based on the consensus views of experts are nevertheless an effective way to set the record straight, set the agenda and hold him accountable.

Not just some more testing — magnitudes more

There aren’t nearly enough people being tested right now even to meet our most obvious, immediate, first-stage needs: diagnosing people with symptoms and testing at-risk health care workers.

But moving forward, the problem is way worse than that: The scale is all wrong. If the goal is to get the virus under control enough that it’s safe to go out again, we need testing to be increased to a whole different level.

Danielle Allen, a Harvard political science professor and director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, explained this in a Washington Post opinion column on Monday:

Some 20 to 40 percent of people infected with the novel coronavirus are asymptomatic. They are significant disease “vectors.” To control the disease without mass stay-at-home orders, you need to be able to test broadly enough to find those asymptomatic people and to find their contacts and test those people, too.

If you want to turn around our current paradigm — so that instead of everyone staying home for fear of getting infected, it’s only the people who are infected who stay home — you need to find them, trace their contacts and isolate them.

And that, Allen writes, means increasing the number of tests from the current levels of about a million a week to something more like five million a day.

That’s a 35-fold increase over today.

The center at Harvard that Allen directs published a hugely significant new Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience on Monday, representing the findings of a bipartisan group of experts in economics, public health, technology and ethics from across the country.

It’s those experts who agreed on the need to deliver at least 5 million tests per day by early June to help ensure a safe social opening. They also concluded that the number will need to increase to 20 million tests per day by midsummer to fully remobilize the economy.

That’s a 140-fold increase over today.

They explained:

What we need to do is much bigger than most people realize. We need to massively scale-up testing, contact tracing, isolation, and quarantine — together with providing the resources to make these possible for all individuals….

Massive testing is essential because it is more finely targeted — more of a precision device than a blunt instrument. Rather than giving an entire city a stay-at-home order of indefinite duration, only those who are infected would need to stay at home or in a medical facility, and only for the specific amount of time required by the course of the disease.

Only the federal government can make this happen

Ramping up the kind of production capacity to deliver anything close to 5 million to 20 million tests per day will be an immense and tremendously complicated task — not to mention wildly expensive. No institution but the U.S. government could even contemplate taking it on.

As the Harvard report explains:

Achieving a testing program at this scale requires supply-chain management and production capacity to deliver 5 to 20 millions of tests per day; distribution capacity to get these millions of tests to last-mile delivery personnel at the local level; and test administration personnel — a combination of local health care workers and service corps members, reinforced by state and national service corps (including entities like the Medical Reserves, U.S. Public Health Service Corps, and National Guard and, during the period of the emergency, AmeriCorps and Service Year Alliance). These service corps would need to be expanded.

Massively scaling up testing itself will require (1) coordinating the ramp-up of existing capacity for test production and analysis; (2) integrating the ramp-up of innovation-based capacity; and (3) building the supporting infrastructure.

And as currently structured, even the federal government can’t do it, according to the Harvard experts. So they urge the establishment — either by the president or by Congress — of a Pandemic Testing Board:

Implementation of such a complex supply chain at this speed requires tight coordination most naturally facilitated by a Pandemic Testing Board (PTB), akin to the War Production Board that the United States created in World War II. The market has not so far supplied the necessary scale of test production. The basic problem is a classic one of coordination and planning that almost always afflicts complicated supply chains that need to be set up rapidly.

Right now, the supply chain is a mess, they write. This part is fascinating:

Almost every link in the testing architecture from the final mile in cities and states back through the laboratories that process tests, the machine manufacturers, the factories producing RNA reagents, etc. report almost an identical story. All fault the other links in the chain for either lacking the relevant supply or demand to scale up, and all argue that what they have heard from others is that further supply is impossible or further demand is not forthcoming. Technologists argue that there is little point in producing tools for contact tracing given the lack of testing capacity, while test producers claim no one will want tests.

Such systemic finger-pointing, lack of common understanding, and disintegration are the classic hallmarks of the coordination failures that occur in complex, interdependent systems that need to rapidly change to serve a new demand. In virtually every successful historical example of such rapid coordination, a central authority has set goals and ensured that each part of the chain meets the interlocking goals required for the chain to succeed. This authority must have clarity on the levels in the supply chain and the kinds of output required at each level to reach desired targets and must induce all parts of the chain to act in conformity with this plan, to avoid failure in one part that would sow systemic distrust.

In the absence of a Pandemic Testing Board, another roadmap — “A National COVID-19 Surveillance System: Achieving Containment,” from Duke University’s Center for Health Policy — calls for the Centers for Disease Control, which has been largely marginalized by Trump, to take the lead in coordination.

So let’s ask Trump: Will you form a Pandemic Testing Board? Don’t you agree that the challenge before us is akin to a war? Will you empower the CDC? Or are you condemning us to a future of finger-pointing and failure?

And if he says everything is great, respond with some reality.

It’s a mess

Christopher Weaver and Rebecca Ballhaus of the Wall Street Journal had a bravura story on Monday exposing just how badly the disarray, shortages and backlogs in the current supply chain are hampering testing, even at its current scale:

The private sector hasn’t so far been able to deliver nearly enough tests to meet the huge demand in the U.S., more than six weeks after the Food and Drug Administration allowed private companies to manufacture test kits and put them to use without having to be approved.

A signal White House effort to ramp up testing showcases the obstacles. Federal officials sought to distribute a new device by Abbott Laboratories around the country, but the push fell short when supplies proved scarce and the device’s reliability faced doubts, according to state officials and laboratory experts.

The article, which is not behind a firewall, supports the Harvard findings:

Absent a clearly organized system for allocating materials across the industry, “it feels a little bit like natural selection, doesn’t it?” said Andy Last, the chief operating officer at Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., a California-based laboratory equipment manufacturer.

On testing, Trump is at his most vulnerable — and defensive

Trump has always had a hang-up about testing. Early on in the coronavirus crisis, he made it clear that he measured his success by the number of infections in the U.S. — making testing a low, if not negative priority. He marooned a cruise ship to keep the numbers down. As Marcotte argued in the Salon column linked above, it seems plausible he simply doesn’t want Americans to know the real numbers, and views testing as damaging to his re-election campaign.

Trump’s lies about testing have consistently been among his most brazen, right through to the present.

“We have tremendous testing, tremendous testing capability,” Trump said on Monday. “Remember this, we’ve tested more than any country in the world by far. In fact, I think I read where if you add up every other country in the world, we’ve tested more.”

But our per capita testing rate is far below several other countries, and the rest of the world has actually done four times as many tests as we have.

He said “our numbers are doubling … almost on a weekly basis” — when they’re actually flat.

And he said the widespread, fact-based, expert-supported concerns about testing are simply partisan attempts to take him down. “Oh, we’ll get him on testing,” he said, mimicking his enemies. Later, he launched into a screed:

But remember this, we’re dealing in politics. We’re dealing with a thing called November 3rd of this year. Do you know what November 3rd represents? Right? You know better than anybody in the room. November 3rd of this year, it’s called the presidential election. No matter what I do, no matter where we go, no matter how well we do, no matter what, if I came up with a tablet, you take it and this plague is gone, they’ll say Trump did a terrible job, terrible, terrible. Because that’s their soundbite. That’s the political soundbite. They know the great job we’ve done.

This has been going on for a long time. Even three weeks ago, Washington Post reporter Philip Bump was able to report how consistently Trump had lied about testing.

There was that conference call with governors in late March where Trump insisted “I haven’t heard about testing in weeks,” even though complaints about testing had been constant — especially after Trump declared in early March that anyone “that wants a test can get a test,” and called the tests as “perfect” as the communications he had with the Ukrainian president that got him impeached.

As Bump wrote:

There have been several phases to Trump’s public assurances about testing. In the first, he and his administration conflated the number of available kits with the number of tests that could be conducted, giving a false impression that testing was widely available. In the second, he criticized his predecessor’s administration for limiting the ability to conduct tests by forcing a reliance on government labs. In the third, he’s emphasized the number of tests being completed, particularly in the context of South Korea, whose broad testing regimen has been credited with keeping the number of cases in that country low.

His current strategy is to blame the governors.

For the record, Trump capped off his Monday defense with a shocking new promise. “We have tests coming out perhaps over the next two weeks that will blow the whole industry away,” he said. “If it comes out, it’ll revolutionize the whole world of testing.”

He offered no details.

Governors can’t do it themselves

Aside from being a sad and pathetic example of passing the buck, Trump’s continued attempt to blame the governors for his own failing is simply nonsense — as the governors are increasingly making clear.

At Monday’s briefing-room event, Trump gleefully quoted New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo acknowledging a big state role in testing. But consider what else Cuomo said:

The national manufacturers say they have supply chain issues. I’d like the federal government to help on those supply chain issues…. This is a quagmire.… Should the states take the lead on the tests? Yes, that’s exactly right. But we need the volume and the volume is going to be determined by how well those national manufacturers provide the kits to the 300 labs in New York.

On April 17, Cuomo said:

The president doesn’t want to help on testing…. I said the one issue we need help with is testing. He said 11 times, “I don’t want to get involved in testing. It’s too complicated. It’s too hard.” I know it’s too complicated and it’s too hard. That’s why we need you to help. I can’t do an international supply chain. He wants to say, “Well, I did enough.” Yeah, none of us have done enough. We haven’t, because it’s not over.

Noting that some of the key elements in the supply chain currently come from China, Cuomo explained:

The federal government cannot wipe their hands of this and say, “Oh, the states are responsible for testing.” We cannot do it. We cannot do it without federal help. I’m willing to do what I can do and more, but I’m telling you I don’t do China relations. I don’t do international supply chain and that’s where the federal government can help. Also remember, the federal government at the same time is developing testing capacity. So we wind up in this bizarre situation that we were in last time, 50 states all competing for these precious resources. In this case it’s testing and then the federal government comes in and says to those companies, “I want to buy the tests also.” This is mayhem. We need a coordinated approach between the federal government and the states.

Cuomo is hardly alone. Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam said on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday that governors are “fighting a biological war … without the supplies we need.” He called Trump and Pence’s insistence that there is enough testing capacity “delusional.”

On the same show, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, said:

I think this is probably the No. 1 problem in America, and has been from the beginning of this crisis, the lack of testing.

And I have repeatedly made this argument to the leaders in Washington on behalf of the rest of the governors in America. And I can tell you, I talk to governors on both sides of the aisle nearly every single day.

The administration, I think, is trying to ramp up testing, and trying — they are doing some things with respect to private labs.

But to try to push this off to say that the governors have plenty of testing, and they should just get to work on testing, somehow we aren’t doing our job, is just absolutely false. Every governor in America has been pushing and fighting and clawing to get more tests, not only from the federal government, but from every private lab in America and from all across the world. And we continue to do so.

Similarly, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said:

You talk to any epidemiologist, and they tell you we should be testing between 1 and 2 percent of our population regularly. And that’s precisely why we need these fundamental supply chain issues addressed, so we can ramp up our testing, and have some confidence in the numbers, and know when it’s safe to engage, and be able to track folks after we have started to re-engage parts of our economy.

On April 14, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker told NPR, “The truth is that the federal government has really been more of a hindrance than a help in most of the testing issues.” He continued:

We got very little from the federal government. We’re now up to almost 8,000 a day. We need to get past 10,000. And frankly, we’re going to need a lot more than that if we’re going to start to think about, you know, how we reopen the economy.

The $484 billion coronavirus relief bill that the Senate passed on Tuesday afternoon includes $25 billion for testing, with $11 billion of that going directly to the states.

But that’s hardly likely to change Trump’s tune on testing. Politico Playbook on Sunday shamefully turned over the top of its newsletter to an anonymous “senior administration official” who said that the talk about testing “misses the real issue.” That official argued that the new funding from Congress would “only fund a lethargic bureaucratic process that had already failed to provide the testing innovation comparable to the private sector.”