A great many of us tend to see the world as divided into those who believe in God and those who believe in science. But the truth is, there's a whole spectrum in between those two points. And there's a very strong chance that the food you're putting on your table tonight got there via folks who go to church on Sunday and are using sophisticated farming techniques that require precision and innovation. Those aren't contradictions.

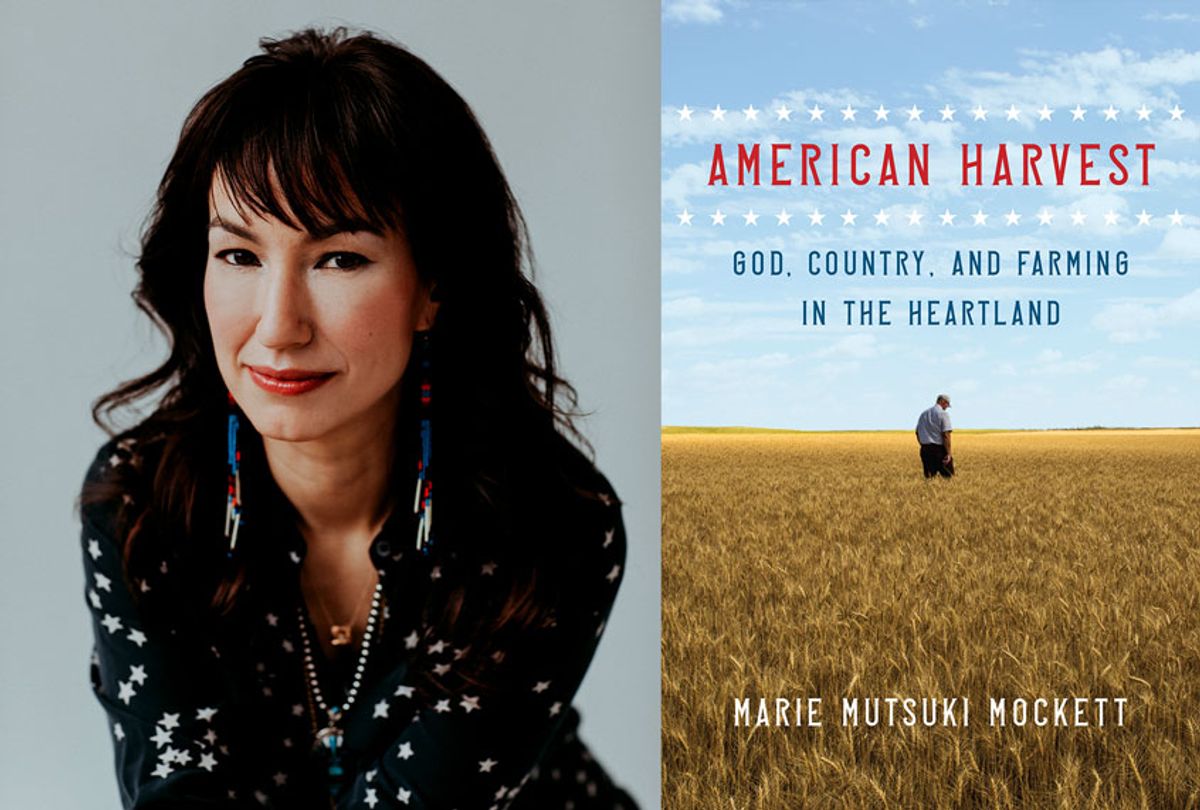

Part memoir, part history lesson, part contemporary reporting, author Marie Mutsuki Mockett's "American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland" is a wise, clear-eyed and intimate exploration of a side of the food industry that few of us ever get to witness. When the California native connects with her family's wheat farm in Nebraska, she decides to join a group of Christian workers to follow the harvest. With a curious mind and an open heart, Mockett learns about both the complex world of growing crops and the even more complicated experience of belief. And at a time when Americans are gaining a profound new appreciation for the wheat that sustains us — and lessons in the ideals that divide us — it could not be more well timed.

Salon spoke recently to Mockett about faith, farming and what it means to a "kind ambassador" in the world.

Why was this was the story that at this point in your life you felt you wanted to tell and that you felt needed to be told?

My previous book had been set in Japan, and I thought it would be really nice to not have to travel internationally and to be conversing in English, which I thought was going to be easier. It ended up being very challenging, because I really did have to learn a couple of new languages, in a sense, in order to communicate with the people who are in the book. I had wondered about the different attitudes toward the intersection between science and religion and food. That had initially intrigued me. I was aware of some stereotypical ways in which the coasts and the interior of the country viewed each other. I thought, that's just the way that it is.

But this question of why was everybody in the city was so interested in organic food and believed in evolution, while people who didn't necessarily believe in evolution were open to GMOs was like a very basic contradiction I found fascinating. That was my entry point, and the fact that I knew that there hadn't really been a book written about farming. I think the farming is interesting, and I think these people are interesting and the world of farming is interesting, and nobody in New York knows anything about the way that combines work. Yet it's vital to the way that we live. All of that kind of came together and intrigued me.

It was eye-opening for me, as someone who truly had not previously given a whole lot of thought to where our wheat comes from.

It's funny because right now everybody's doing all this baking!

I knew a little bit of the debate or the complexities of the debate around GMOs, but many people just have the message that GMOs are bad.

I don't think that I'm an expert. I certainly read a lot and tried to present a lot of information in the book. I remember years ago, my father just saying in this offhand way, "Well, it sounds like organic food is finally making a profit." He said it in a way to imply that he thought organic food was kind of funny. He didn't think terribly highly of the endeavor. I knew that his attitude, even though we lived on the west coast, was that organic food was silly. I knew that my peers, increasingly as I went though life and had been on the same trajectory I was on, really valued organic food. But I had never really sat down and examined what the attitudes were and why they were there.

I also did not know, going into this, just how how rapidly our farmland has been disappearing in this country. You talk about the Wheat Belt and you talk about the quality of the wheat, how it varies from place to place. What are you thinking now when you see where we are in terms of having to really know these things and care about them?

This whole topic was of interest to me because I am always interested in how what we believe shapes our reality, and then where the problems are in what we believe. It's very inconvenient if you think that your food has to be a particular way, and it's being created by other people. If one is making one's decisions about food in the store, I think it can give you a false sense of control and a false sense of knowing how that world is constructed. It's very inconvenient to think, "No, I can't have my food exactly the way that I wanted. If only those people would just do what I say and make my food the way that I want it, everything would be fine." It's inconvenient to learn that's actually a little bit more complicated than it sounds.

We were also captivated in the news by the burning of the Amazon rainforest last summer. A lot of that was that the forest just being burned to clear ground to make room for soybeans to be grown, which is exactly what the guys talk about in the book where they say that 37-38% of the arable surface area on the planet has been dedicated already to food production, unless we burn forests. We were very upset about the burning of the Amazon rainforest, but then the other piece was that it was to clear ground to raise more crops, partly because Trump had suddenly put a tariff on soybeans. American soybean farmers were having difficulty selling their soybeans to China, which still needs soybeans because China doesn't actually produce enough food to feed its own population. That piece of the story got left out most of the time.

I think that it's inconvenient to have to put the whole picture together. I also think that the internet makes us feel, and makes me feel, close to the world and like I understand everything everywhere. Of course I don't, and I think that's true of food production. How can one possibly understand everything about everything we eat and keep track of it all? That's not possible. You do rely on people to become experts in different areas in life. But the internet does make us feel like, "I understand the world and I understand where everything comes from. If everybody would just do these things the way that I want them to, then everything would be better. " It's not quite that simple.

It is not an easy thing to weave in faith and farming and identity and all of these other nuanced things into one large story. You explained how we have a bent for doubt built within us, but then doubt is what makes us feel so scared and alone at the same time. We're feeling and experiencing all of that so profoundly right now. It brings us loss.

[In the book] somebody says, doubt is like a testing mechanism. This is useful, it makes sense. If somebody doubts the earth is flat, that's helpful. But then we can also get very scared. Over the last few weeks, once we started sheltering, I have consciously said to myself, you have to reimagine how your life is going to be. I don't know what the world is going to look like. I could consciously say to myself, I'm being asked to adapt to a new reality, but that doesn't mean that I'm adapted to it. That's what crisis does.

It was interesting to see how doubt and questioning and how nuance really does play out within these communities of faith. We hear the loudest voices, regardless of where they're coming from, whether you're on the right or the left.

It's always easier to characterize the other with a sharp image. The people that I was traveling with are very devout Christians, but it isn't as though I was traveling with people who adhere to a form of a Jimmy Swaggart Baptist faith. That would have been a lot harder for me to access. One of the things I came to understand was how diverse the Christian world is. It did reveal to me how that diversity very often isn't portrayed, which I think is unfortunate. One of the things that I really did have to do in writing the book was to say, "I don't really know what Christianity is."

If I had gone in thinking I know what Christianity is, then a lot of the stories that happened and a lot of the doubt that people shared would not have opened up in front of me. By starting by thinking that I didn't actually know what it was, then I had room for those stories. The other thing I had come to realize is this question of what is Christianity is historical, and people have been asking it forever.

You describe yourself as trying to be a kind ambassador from your world. It's hard to do that when you are put into different circumstances where maybe everyone isn't in lockstep, you're not in your silo, you're outside of the comfort zone where people agree with our worldview. You also talk about that confirmation bias that we have that is built into our wiring as well. To reach past that and say, "How can I be a kind ambassador from my world?" feels like such a simple concept, but so hard to practice.

I think that's one of the reasons the last two books I've written have had to do with traveling. When you travel, you are forced to figure out who you are because you're constantly placing yourself in unfamiliar surroundings.

It seems so fitting that the book ends with you back in San Francisco, knowing that you have the luxury of getting what you want exactly the way that you want it. Now we are at this moment where none of us can get what we want to exactly the way we want, and in certain states people are protesting because they can't get what they want the moment that they want it. What do you feel you learned from that experience of being out there where things were a little harder, required more time and patience and quiet of listening to others rather than necessarily speaking everything on our minds? How has that served you in this particular moment that we're all living in together now?

I left San Francisco and I brought my son and I came to my childhood home, which is down on the Monterey peninsula. [When] I put on my gloves and my mask and I went to the grocery store, there were no vegetables that day. I came home and thought, "I guess my parents were right all these years they were raising their own vegetables, and I was so tired of having to weed the garden and do all this stuff. I guess I should plant vegetables."

My mother had laid out seed packets. She was all prepared to plant the year's vegetables. I went and planted the vegetable garden the next day, and then I found that the pantry was stuffed full of toilet paper because she had planned ahead for months, to always make sure the house had enough toilet paper.

One of the things that the the agricultural world does that I value is they try to solve problems and fix them themselves. They really prize that problem solving and self-reliance. There are certain problems that I can't solve. If we get sick, I will call my doctor. But there are certain things that I can take on myself. There are ways in which we're all more capable than we realize. We can sew on buttons, we can do our sourdough starter. We can not demand perfection out of ourselves when we educate our children, but we can teach them some basic math and English. All of that is possible. I think about that ability to be self-reliant and try to take care of ourselves as much as we can, and not panic. And then cooperate in areas where we have to cooperate, obviously around issues related to the virus and medical care and research.

This is a story about that finding that sweet spot of self-reliance and collaboration and cooperation, and finding it through faith and farming. It made me want to be a kind of ambassador in the world.

One of the things that happened in the course of writing the book is that I walked away with an understanding what Christianity means to me. Sometimes I meet people who have like the same idea of what Christianity is, and I like our understandings overlap and that feels comfortable. Then sometimes I meet people who believe in a form of Christianity that feels really distorted and ugly, but it doesn't shake what I think. I just accept that they believe this form that I think is destructive. But I have a context for it now, which I did not have before. That's been helpful to me. People have, throughout history, fought to take control over what the narrative is for Christianity. That is a historical struggle that's been going on for centuries.

It's about seeing people as people, as opposed to just their ideologies.

I'm concerned that people don't think the book is somehow apologizing or avoiding difficult questions because we do, in our conversations in the book, get into all of the ugly issues around evangelical Christianity, et cetera. I definitely don't want people to walk away thinking I'm saying that they have to diminish their beliefs. That's important to me.

Faith is complicated and it's really hard to say to somebody, "You should wake up in the morning and feel great, just because you should." Sometimes it does require faith in something just to get you going. That's why I think that the ancient faiths matter, and still matter.

Shares