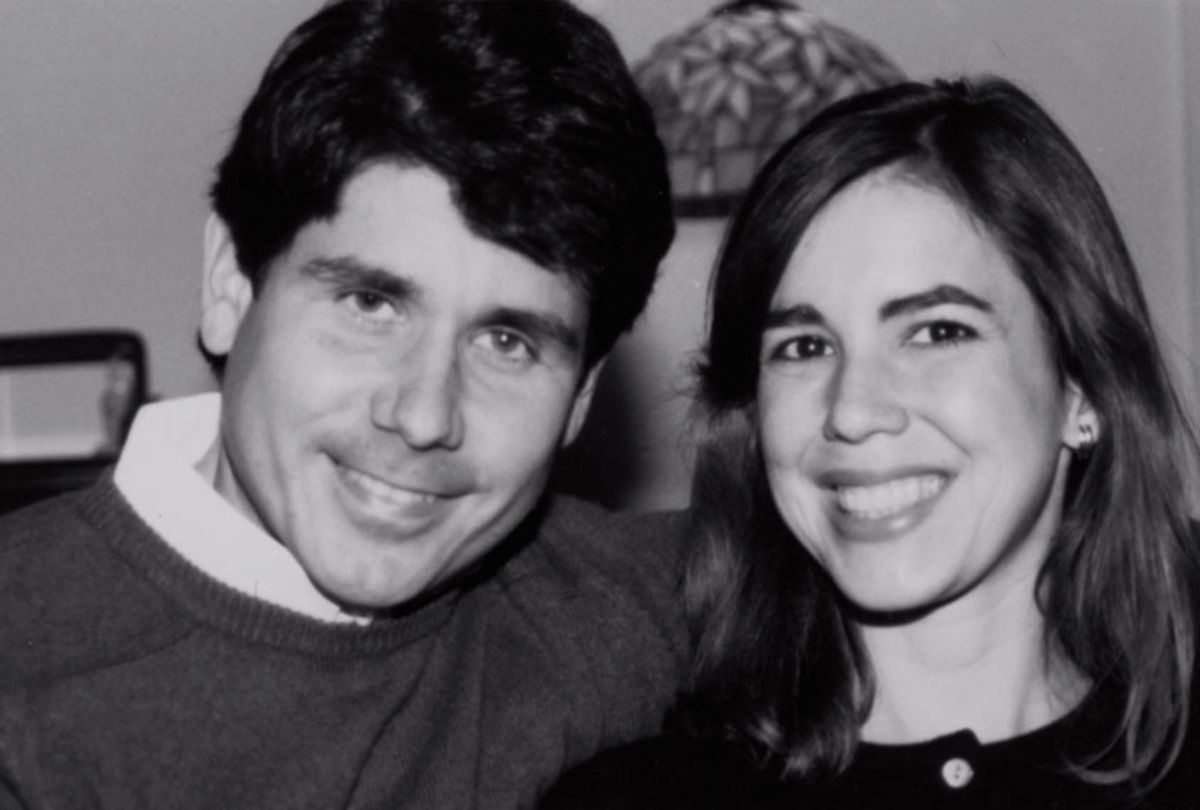

Twelve years ago, Illinois governor Rod Blagojevech was arrested for his part in a scheme to sell or trade Barack Obama's Senate seat, which Obama was vacating to assume the presidency, to the highest bidder. He had been taped by the FBI, saying: "I've got this thing, and it's f**king golden. I'm just not giving it up for f**king nothing."

It was an explosive quote that, once it reached the media, turned the arrest into an overnight scandal; Blagojovech's approval ratings plummeted, but his television airtime skyrocketed. While he had been something of a media hound throughout his career — known for his flamboyant style, charisma and political grandstanding — Blagojevich aggressively made the rounds on cable and late-night, proclaiming his innocence while awaiting trial.

"The View," "The Today Show," "Morning Joe," "The Ellen Degeneres Show," "The Celebrity Apprentice" — he was on them all.

"While he may be the nation's least popular governor, he has been the most popular news story," one local anchor said at the time.

This dichotomy, the way media can both completely make and destroy an individual or a legal team's carefully constructed narrative, is explored in the new Netflix docuseries "Trial by Media." Each episode of the six-part series — executive produced by George Clooney, Court TV founder Steven Brill and New Yorker legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin — reviews a different legal saga through the lens of how journalism (in its broadest sense, tabloids and shock jock radio included) potentially affected its public reception and ultimate outcomes.

The cases include following: the 1995 murder of Scott Amedure who was killed by Jonathan Schmitz (whom Amedure admitted to having a crush on during a live taping of "The Jenny Jones Show"); the attempted murders of the "subway vigilante"; the rape of Cheryl Araujo in 1983; the fraud and money-laundering trial of former HealthSouth Corporation CEO Richard Scrushy; the police shooting of Amadou Diallo; and the Blagojevich trial.

Each of these cases commanded public attention during the eras in which they played out, and what "Trial by Media" does exceptionally well is distill, in under an hour, the "big takeaways" from each episode. It's similar in format to Netflix's "Dirty Money."

It addresses the ways in which race dominates — both overtly and subtly — media narratives. There's the evident and essential need for anonymity for victims, especially victims of sexual assault, during televised trials.

Then there's the question of the value of televising criminal proceedings, especially after the advent of the 24-hour news cycle. This inquiry is the closest "Trial by Media" comes to a throughline, however. The series is missing an overarching synthesis about how or why viewers should reinterrogate their relationship with crime and court television, especially in the age of true crime.

There's a full slate of recent documentaries that articulate this point more intentionally, using more current examples, like 2016's "Beware the Slenderman" and Erin Lee Carr's "Mommy Dead and Dearest" and "I Love You, Now Die." In these, the cause and effect of how the media shaped the perception of the victims and perpetrators of these cases via reductive headlines is made clear.

"I Love You Now Die" tells the story of beautiful, blonde suburban teen Michelle Carter, who urged her 18-year-old boyfriend, Conrad Roy, to purchase a portable generator and run it while he sat in his locked truck, which was parked in a Kmart parking lot in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Roy apparently became scared as the toxic fumes clouded his vehicle and exited the truck; Carter texted him to get back in. Then on July 13, 2014, Roy died by suicide.

In her film, Carr pushed back on the media characterization of Carter as an attention-seeker, and instead revealed her to be self-destructive, an outcast, yet also a stellar student and community member. Could Carter really be this manipulative femme fatale? Or was she also a child who, like Roy, needed help? Or is the truth found somewhere in the middle?

Carr had over two hours to explore the intricacies of this single case and the media response to it, so it makes sense that the documentary's interrogation of the accepted narrative would be more polished than "Trial by Media's" survey of six individual cases.

But "Trial by Media" does hold an important place in moving the conversation about true crime programming forward. In recent years, the genre's narrative is less about solving a mystery and more about turning the magnifying glass on the legal proceedings that surrounded it; a sort of "true criminal justice" designation as opposed to "true crime."

Docuseries like "Making a Murderer," "Confession Killer" and "The Prosecutor" complicated the simple, salacious true crime narratives that had become so prevalent during the daily Lifetime and Bravo lineups, wherein there are clear-cut good characters — the victims and law enforcement — and the bad character — the killer or the criminal. In these series, this formula is upended, revealing that even the "good guys" can have bad intentions, like potentially framing a man for murder to keep the state out of debt or allowing a man to confess to murders they know he didn't commit just to clear the case books.

In "Trial By Media," we're introduced to another variable — the journalists, television personalities, and story spinners whose effect on justice can't be understated. It's a focus that should be more present in true crime content moving forward because thanks to how everyone accesses information digitally at all times, the court of public opinion has been in session and shows no sign of being adjourned anytime soon.

"Trial by Media" is now streaming on Netflix.

Shares