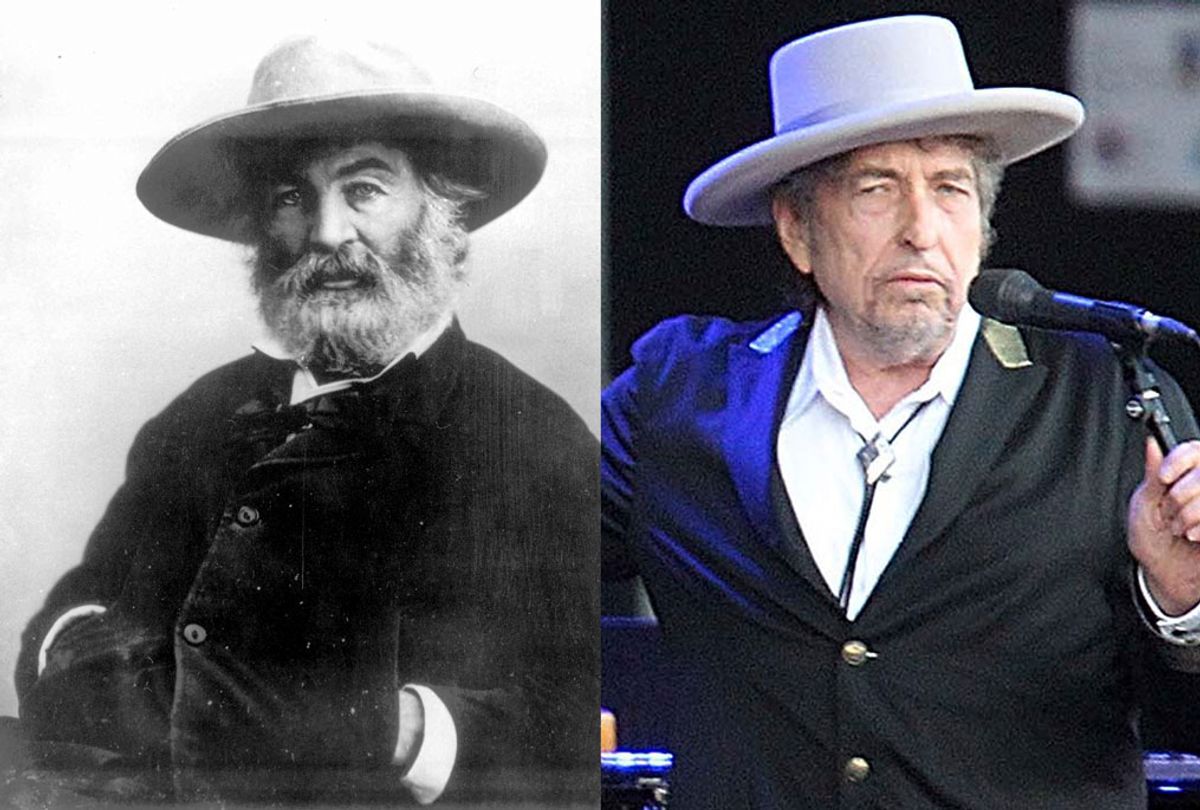

Dylanologists had to work overtime in March with the sudden appearance of "Murder Most Foul," a 17-minute track revolving around the Kennedy assassination and packed with allusions to 20th-century music and pop culture. Its title, of course, alludes to Shakespeare's "Hamlet," that cornerstone of English literature. Which makes the title of Dylan's follow-up track, "I Contain Multitudes," all the more intriguing — as English majors everywhere will recall, the phrase occurs near the end of Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself":

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

While his place in American literary history is not quite as exalted as Shakespeare's in the British tradition, Whitman is widely regarded and taught as the "poet of democracy," the writer who set out to speak in a uniquely American language of expansiveness and inclusiveness — yes, he contained multitudes. And so, apparently, does Dylan, or so he would have us believe with his two new singles.

For those who may have dozed off midway through their American literature surveys, Whitman's "Song of Myself" and the rest of his first collection, the 1855 "Leaves of Grass," are unlike any English poetry that had come before. And though it took a while for the influence of this radical new style to be felt, it opened the doors for free verse as a form and brazen honesty as a disposition. Whitman isn't the writer of the poem so much as he is the poem, and more: he begins, "I celebrate myself, and sing myself / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you." Some sections of the poem are made up of "catalogs," lists of people, places and things that inhabit the poem and poet. "I am afoot with my vision," he tells us, and that vision takes him, and us, everywhere. He is a seaman, a hunter, a soldier, a "hounded slave," a "mash'd fireman with breast-bone broken." He identifies with a woman trapped in her husband's house, longingly watching men bathe in a nearby river.

Dylan takes a similar approach in both new songs. "Murder Most Foul" includes a section that rattles off an eclectic playlist, reminiscent of the Theme Time Radio Hour he hosted from 2006 to 2009.

Play me a song, Mr. Wolfman Jack

Play it for me in my long Cadillac

Play me that "Only the Good Die Young,"

Take me to the place where Tom Dooley was hung.

Play "St. James Infirmary" and the Court of King James

If you want to remember, better write down their names.

Play Etta James, too, play "I'd Rather Go Blind,"

Play it for the man with the telepathic mind.

But naturally, he sounds even more like Whitman on "Multitudes," as he calmly, almost wistfully, explains all he contains: 24 of the song's 44 lines begin with "I" or "I'll":

I'm just like Anne Frank, like Indiana Jones

And them British bad boys, the Rolling Stones

I go right to the edge, I go right to the end

I go where all things lost are made good again

I sing the Songs of Experience like William Blake

I have no apologies to make

Everything's flowing all at the same time

I live on a boulevard of crime

I drive fast cars, I eat fast foods,

I contain multitudes.

While Dylan's pose as a 21st-century Whitman is something of a new development, his affinity for mid-nineteenth-century American literature and culture — a period known to scholars as the "American Renaissance" — spans his career. In his 2004 memoir "Chronicles, Volume One," he recalls a period in the early '60s, just before he hit it big, spending days in the New York Public Library reading newspapers from the 1850s and '60s on microfilm. "I wasn't so much interested in the issues as intrigued by the language and rhetoric of the times. . . .There were news items about reform movements, antigambling leagues, rising crime, child labor, temperance, slave-wage factories, loyalty oaths and religious revivals."

Later he describes walking the streets of New York thinking about his literary forbears: "On 7th Avenue I passed the building where Walt Whitman had lived and worked. I paused momentarily imagining him printing away and singing the true song of his soul. I had stood outside of Poe's house on 3rd Street, too, and done the same thing, staring mournfully up at the windows." On "I Contain Multitudes" Dylan sings, "I got a tell-tale heart, like Mr. Poe / Got skeletons in the walls of people you know." Fifty-five years earlier, he ended the song "Love Minus Zero/No Limit" with a nod to another Poe classic: "My love, she's like some raven / At my window, with a broken wing."

Another New Yorker — and contemporary of Whitman — whom Dylan repeatedly references is Herman Melville. Just as he was going electric in 1965, Dylan riffed on "Moby-Dick" with "Bob Dylan's 115th Dream," a six-and-a-half-minute postmodern epic featuring Captain A-rab's abandoned pursuit of a whale. He spent a portion of his Nobel Lecture in 2017 giving an explication — which owed a considerable debt to SparkNotes — of Melville's great novel.

Not that Dylan has confined himself to canonical writers of the period. Among his most celebrated borrowings from other writers (plagiarisms, to the unhip) is his deep dive into the poet laureate of the Confederacy, Henry Timrod, to come up with a handful of phrases scattered throughout his 2005 album "Modern Times."

But on these two new singles, it is clearly Whitman that Dylan has on his mind: "I'm a man of contradictions, I'm a man of many moods." If claiming Whitman's mantle seems a bit presumptive, it's worth remembering that Dylan is one of only eleven Americans to receive the Nobel Prize in literature. That selection was not without controversy, which may have partly inspired Dylan's strongly-implied self-comparison to a guy who surely would have won a Nobel Prize if it had existed in his lifetime. Whitman, no doubt, would have agreed with that assessment: he was a relentless self-promoter, from the first publication of "Leaves of Grass" — "Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the son, / Turbulent, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking and breeding" — to his final years, when he was increasingly revered by devotees known to early biographers as "hot little prophets."

The philosopher William James wrote that Whitman "has infected them with his own love of comrades, with his own gladness that he and they exist. Societies are actually formed for his cult . . . he is even explicitly compared with the founder of the Christian religion." Dylan can surely relate to that kind of adulation — fans knocking on his door, rifling through his garbage — though he has never embraced his own cult the way that Whitman welcomed disciples. He has, however, been happy to exploit his own mythical status, whether by starting his own Heaven's Door whisky brand or by teaming up with Martin Scorsese to make a documentary, "Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story," that deliberately blurs fiction and reality, winking at viewers as it stokes Dylan mythology.

In 2014, Dylan raised what was by then a familiar cry of "sellout" by starring in a Chrysler ad aired during the Super Bowl. It begins with the head-scratcher, "Is there anything more American than America?" and works its way through images of James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, cowboys, and, of course, Bob Dylan, on its way a to a Detroit assembly line and an encomium to "American pride." For Dylan, shilling for Chrysler was actually yet another defiant act, giving the middle finger to those members of his generation who still cling to an image of him as a principled countercultural sage.

At the same time, Dylan looks completely at home in that parade of Americana and patriotism. Whitman would have, too. In addition to the famous "I Hear America Singing," he wrote poems about Columbus, celebrations of westward expansion and the completion of the transcontinental railroad. Near the end of his life he saw his name and likeness on cigar boxes manufactured in his adopted hometown of Camden, New Jersey.

Although he eventually won cigar-box-level fame, Whitman was not widely imitated in his own lifetime. But the "barbaric yawp" that he sounded in "Song of Myself" echoed throughout 20th-century poetry, registering with particular force on the Beat poets, and especially Allen Ginsberg, who paid tribute to Whitman in "A Supermarket in California." Ginsberg, of course, joined Dylan in a mutual-admiration society, appearing in the famous cue-card video of "Subterranean Homesick Blues" and riding along on the Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan absorbed the Beats' style, and as the original singer-songwriter, he would pass that influence along to a long line of acoustic-guitar-wielding, shaggy-haired imitators. Finally, having watched generations of New Dylans come and go, perhaps the Old Dylan decided it was time to become the New Whitman.

Shares