The Department of Veterans Affairs is taking heat from Congress after rejecting a civil rights group’s request to remove headstones engraved with Nazi iconography from the national cemetery at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas — as originally reported by Salon — opting instead to “continue to preserve” the markers.

In a statement, House Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Subcommittee Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., said the VA’s response — which came the same day that the Anti-Defamation League found that anti-Semitic incidents had hit an all-time high in 2019 — was “callous, irresponsible and unacceptable,” and demanded the department change course.

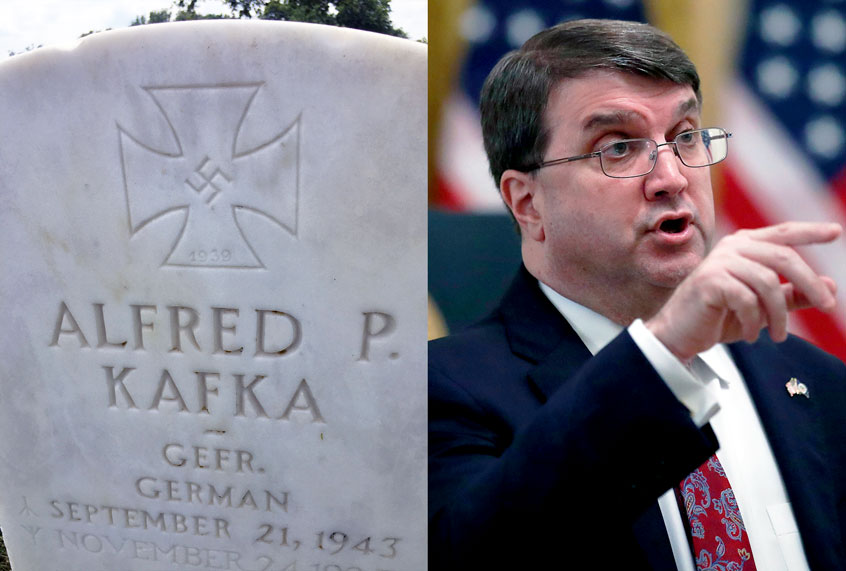

The headstones top the graves of two German POWs who died in 1943 as captives of the U.S. Army. Along with the soldiers’ names and dates of their births and deaths, the milk-white marble is engraved with a swastika in the center of an Iron Cross — the German army’s award for valor — and the phrase, “He died far from his home for the Führer, people and fatherland.”

The initial request came from Mikey Weinstein — a Jewish former service member who now chairs the nonprofit Military Religious Freedom Foundation (MRFF) — who wrote to Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie demanding that the department “immediately replace the gravestones of all German military personnel interred in V.A. National Cemeteries” and remove any other memorials featuring Nazi iconography.

Upon Salon’s publication, Les A. Melnyk, head of public affairs and outreach at the National Cemetery Administration, said in an email that the Trump administration “will continue to preserve these headstones.”

“V.A. is aware of three headstones — two at Ft. Sam Houston National Cemetery and one at Ft. Douglas Post Cemetery [in Utah] — that include these symbols,” Melnyk wrote. “All of the headstones date back to the 1940s, when the Army approved the inscriptions in question. Both Ft. Sam Houston and Ft. Douglas [Utah] cemeteries were subsequently transferred to the V.A.’s National Cemetery Administration, in 1973 and 2019, respectively.”

“The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 assigns stewardship responsibilities to federal agencies, including V.A. and Army, to protect historic resources, including those that recognize divisive historical figures or events. For this reason, V.A. will continue to preserve these headstones, like every past administration has,” he wrote.

A follow-up investigation by Salon could not uncover any similar requests to past administrations. Apparently the only previous mention of the markers in the press comes from a 2012 article in a local San Antonio publication, which paints their presence favorably.

However, retired Lt. Gen. James Peake, a 38-year Army veteran who served under President George W. Bush as the sixth Secretary of Veterans Affairs, told Salon that the Bush administration had never fielded such a request on his watch.

“I don’t recall anything during my tenure, or had any knowledge of them,” Peake said in a phone call.

When asked about his take on the obligations of the Preservation Act, Peake replied, “If that’s what the law is, I certainly support the law.”

That law, however, does not mandate that protected objects retain that designation in perpetuity.

“While this may be a long-standing bureaucratic policy, that is no excuse for allowing it to continue,” said Wasserman Schultz. “It is never too late to do the right thing. I call on the VA to eliminate this antiquated policy and immediately replace these inappropriate and insensitive headstones.”

Weinstein applauded the move. “Now that she has bravely led the way, MRFF implores all other members of Congress of good conscience to timely follow suit and likewise back MRFF’s demands to the VA to eradicate these hideous Nazi memorial headstones,” he said in an email to Salon.

The Fort Sam Houston VA cemetery is home to the remains of 133,154 American veterans, spouses or their children. Its “Section Z” hosts the remains of 140 prisoners of war from World War II, 132 of whom were German.

By the end of World War II, nearly half a million Axis prisoners of war were transferred to about 700 camps in the U.S. The vast majority were repatriated at the end of the war, but POWs who died in the U.S. were buried at their prisons and sometimes reinterred in national cemeteries when camps shut down.

Occasionally, Nazi and anti-Nazi German factions in the U.S. prison camps would fight, and there appears to have been at least one killing: a murder-suicide in Kentucky, after which Nazi POWs draped the Nazi flag over the murdered anti-Nazi as a provocation.

The VA routinely changes out headstones if appropriately requested, such as for typographical errors. The military also keeps a registry of Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers, but neither the Iron Cross nor the swastika appear on the official list.

Swastikas are not legal for public display in Germany, and all known monuments that feature the Nazi symbol have been removed or replaced.